When I was finishing up my PhD, my mother was in a panic to help me find a job. She reached out to her ex-husband, a big wig on the international finance scene, to ask if he would review my CV and application documents. Graciously, he accepted. His assessment was brief: “Clearly you are accomplished, Dr. Jacobs, but you also present as being rather lazy.” He went on to describe to me what it was like to be the reviewer of my application. All he saw was a long list of things that I had done, people that I had worked with, and the deliverables that I had authored. “What does this actually mean?,” he asked.

This one email, sent over 10 years ago, has been the most important contribution to my career advancement success. The idea that reviewers are meant to analyze our applications in addition to evaluating them is problematic. Not only are we opening up our information to biased evaluation, but in this case, and more immediately important, we are signaling to the reviewer that we expect them to do the work in evaluating our candidacy. My finance CV-savant was telling me that he had to do too much work to figure out that I was the right candidate. That made me appear lazy.

Since that time, I have worked hard to provide the analysis and the context of my work. I approach “me” as a researcher would, analyzing temporal trends, highlighting skills, making word clouds, and adding helpful infographics and images. After particularly “dense” parts of the application, I add something more light hearted, a kind of break. When there is something complex and multifaceted in its interpretation, I break it down into categories.

Use research skills to organize and present your CV

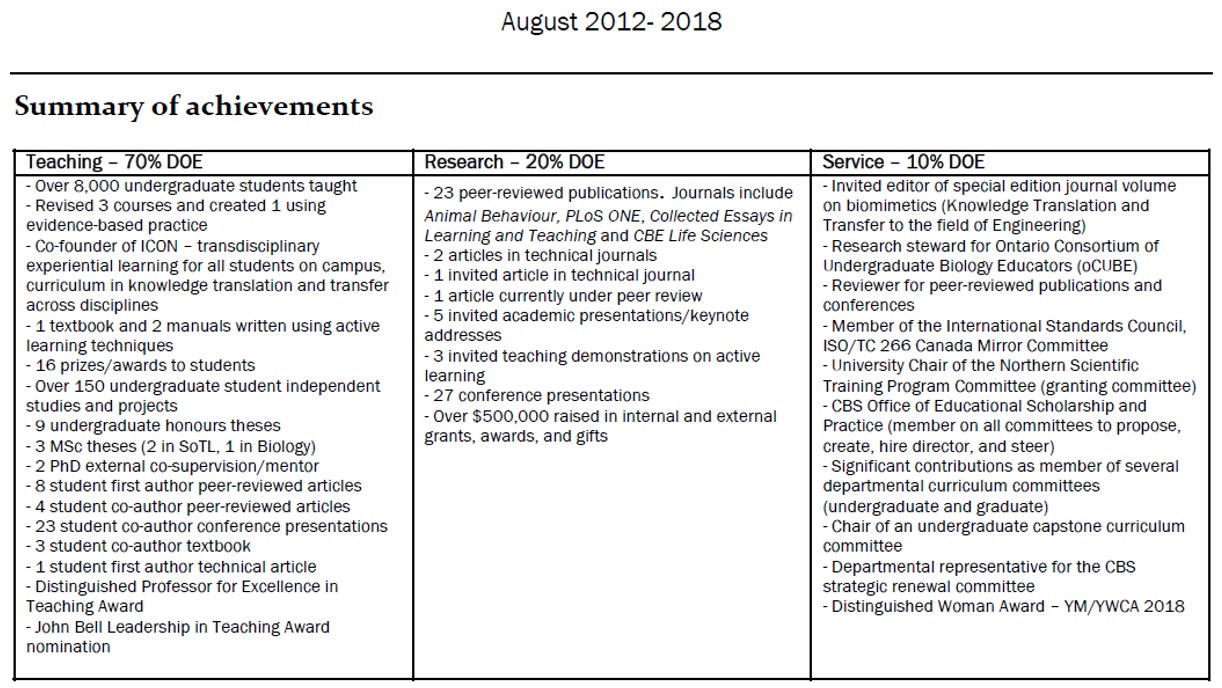

Over the years, this analysis has evolved. As an early career researcher, I began by using the blank space often available on the right hand side of CV pages by dropping in a text box with short lists of “Evidence or Skills Acquired,” or details about the context of a certain CV section. Then, as my career began to generate more data, I added tables and figures. Consider using a table in an executive summary (definitely have an executive summary!) that is broken down into categories. In the academic world, those categories might be Teaching, Research and Service. In these columns, provide summaries of your achievements. It might look like this:

Narratives are as important as lists of evidence. Use them as an opportunity to share the context, acknowledge your colleagues, and share your values. Context is so important. We know this from writing or reading reference letters but we rarely transfer it to our own documents in an application. How has your work stood out? Within which community? How have those contributions changed over time? When you are able to add data, it allows the reviewer to determine a ranking of your work.

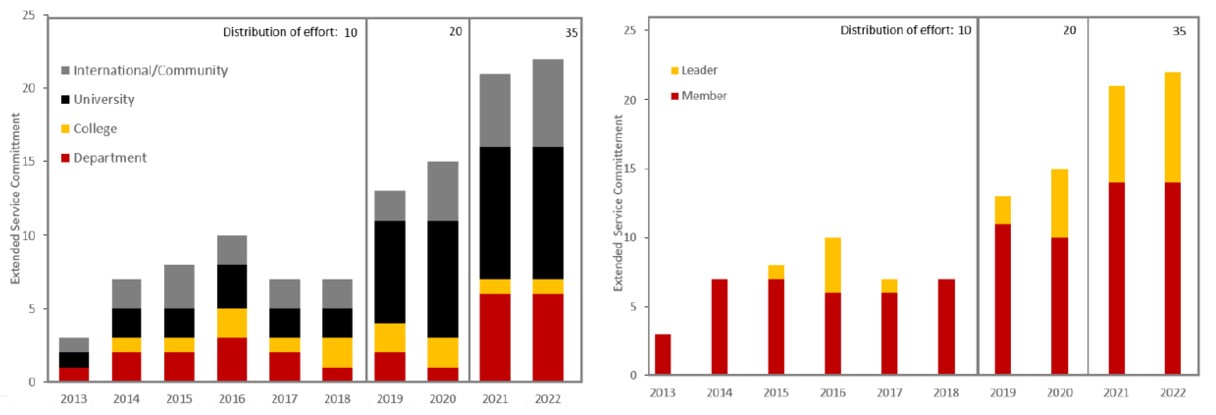

Here is an example of bar graphs used to analyze significant service commitments. The panel on the right shows the scale of the commitment relative to the distribution of effort. The panel on the left shows whether these commitments were as a participant or as a leader.

Word clouds can be used to summarize feedback such as teaching evaluations from peers or students. If you have been teaching for a while, consider highlighting key words that have changed in frequency in the feedback you have received, as an indication of professional growth.

Acknowledging colleagues and sharing your values in action

Acknowledging colleagues in your CV and application needs to be done carefully. For many of us, this could lead your reviewer to conclude that you are not “independent.” Though bias training can be helpful, your application should push the reviewer in the direction of “this candidate is highly sought after and well connected.” You can do this by using the word “I” frequently in descriptions of your work and by acknowledging your colleagues by regional scale at the end. It might look like this:

Collaborators:

Department: Kermit the Frog, Yolanda the Rat

University: Miss Piggy, Animal, Rizzo the Rat

National: Camilla the Chicken, Clifford

International: The Penguins

Sharing your values can be done in several ways. Often you will be asked to write an equity, diversity and inclusion statement. Sometimes that statement will mention “accessibility” specifically. Most of the time it will not. Statements are a good start but they do not speak directly to what your values are. Move beyond the statement into action. How do you apply that statement in your practice? What professional policies guide you that reflect your values? What outcomes of these policies have you observed? What modifications have you made to them? How do they affect your colleagues? Sharing your values in action will give the reviewer a good idea of what working with you might be like. In the academic world, this might be a list of your lab group hiring policies. You might consider sharing how you will support students or colleagues.

In many respects, it feels strange to me to be writing this article, offering advice to job seekers. I’ve been job seeking since 2004 and I’ve only just paused with the submission of my application for promotion to full professor (decision pending). The application is available on my website, along with my application for promotion to associate professor. It’s time that we started sharing our careers. If you have any questions, would like an independent review of your work, or would like to use what I’ve got to craft your own, please get in touch.

Shoshanah Jacobs is an associate professor in the department of integrative biology at the University of Guelph.

Greetings and congratulations Shoshanah, it comes so nice to hear from you again, and what better way to do it than reading this article of yours.

Very well said words, practical, honest, truthful and useful.

Best wishes of joy and success to you.

Cheers

Ludwin the Chilean HM

Ludwin! My sailing friend. So lovely to read your note. I hope that you are well and healthy and safe.

Thanks for this helpful article! I love those bar graphs; they give a compact but surprisingly detailed view of one’s service involvements over time.

“Narratives are as important as lists of evidence.” – no theyre not

“Context is so important. We know this from writing or reading reference letters” – no “we” dont.speak for yourself. reference letters are so subjective that they are not used in many other countries.

No doubt the author meant well. However, I come away disappointed. It is constructed for those on the “inside”. It would have been far better to address the underlying State-academia business model.