Mary Ann Middleton didn’t think it was possible.

When the Earth Science PhD first heard about the 3 Minute Thesis Competition (3MT), which asks graduate students to distill four years of research into a 180 second-long pitch, she assumed it had been created by the same person who thought lethally poisonous fish would make for great entrées.

It wasn’t. 3MT is part of a growing trend of competitions, including SSHRC’s Storytellers Contest and the Alan Alda Centre for Communicating Science’s Flame Challenge, offering awards and prizes to graduate students who can communicate their research in ways that are accessible and meaningful to non-academic audiences.

This new form of knowledge translation requires researchers to deliver content that is clear, concise and jargon-free, and more importantly: entertains, engages and inspires their audience. Though many graduate students would rather take their chances with the pufferfish sashimi than attempt this daunting new form of communication, Middleton would probably urge them to reconsider.

Despite her reluctance, Middleton entered Simon Fraser University’s 2013 3MT competition. “Someone who was interested in my work Googled me and found the video of my 3MT talk on YouTube. They passed it around their office and I got a job interview out of it,” said Middleton.

Middleton is not alone. Krystal Guo, a Mathematics PhD student and fellow contestant was invited to give a talk at an American university as a result of her 3MT presentation. Mina Soltangheis, a Masters student in Interactive Arts and Technology describes the video of her research talk as a ‘digital business card’ that has opened doors to mentorship and business opportunities.

Getting people to understand and be excited about your research can make potential employers understand and get excited about having you on their team. But how do you go about transforming your communication style from descriptive to dazzling? It starts by looking at your research from a very different kind of framework than most academics are used to: storytelling.

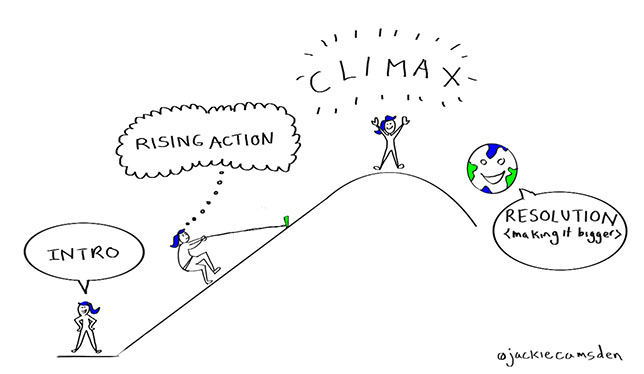

From video games to vampire novels, all narratives are based on this basic story arc formula: Introduction + Rising Action + Climax + Falling Action.

The following outlines how to identify these components within the context of your research:

- Introduction: setting the stage

The problem: All research focuses on fixing something—a knowledge gap, negative attitudes, malfunctioning liver cells. Start here. Setting up a clear and obvious problem gets your audience’s attention and tells them why they should invest the time and energy in listening to you.

Why you are doing it: What motivated you to pursue this inquiry—a personal experience as a child or your love for understanding how things work? It may feel uncomfortable but taking the risk and revealing something about yourself tells your audience that you trust them.

- Rising Action: what are you doing (or planning to do)?

Be my hero: When thinking about your research methods, don’t think of them as methods. You are not an academic, you are the hero of this story, challenging existing ways of doing things, taking risks, and adventuring. Tell your audience why what you are doing is daring, different or new and they will root for you.

Everyone welcome: Now that we’re on your team, make sure to keep us there. Although technical or field-specific words are a handy way to communicate a lot with a little, they risk excluding a large portion of your audience.

Everyone is smart: This is where it gets tricky. Though you can’t go into too much detail in any single communication story, you also don’t want to over-simplify your content. Adding key details to convey advanced concepts demonstrates that you recognize your audience’s intelligence.

- Climax: the discovery

What did you find or what do you hope to find? We all love learning new things. This moment of revelation is the gift you are presenting to your audience. Pause. Breathe. And present it to your audience wrapped in the bows and ribbons it deserves.

- Falling Action: making it bigger

Why does the rest of the world care? Loop back to the beginning of your story and explain how your revelation will not only address the problem you already outlined and how that will make the world a better place. This not only leaves your audience with a tidy, satisfying ending but also will make them feel like they are part of something much bigger.

Remember: the most important point to keep in mind when you are preparing your research story is that it’s not about you. It’s about your audience. Show them that you care about them and they just might reciprocate the sentiment with a job opportunity, speaking engagement, or something even more delicious and exciting than seafood roulette.

Jackie Amsden is Graduate Student Engagement Coordinator with Simon Fraser University’s Office of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Fellows’ Centre for Academic and Professional Engagment.

Thanks for sharing the article on how to tell the story of your research. This is becoming increasing important, especially for those looking to non-traditional research funding options. There are lots of examples (some good and some not-so-good) on http://www.WeShareScience.org. The site has 3000+ video summaries by researchers in various disciplines.