This may seem like a facile question. A PhD is a doctorate (thanks Google), the terminal degree in many fields. It’s what else it is that’s hard to pin down and get people to agree on.

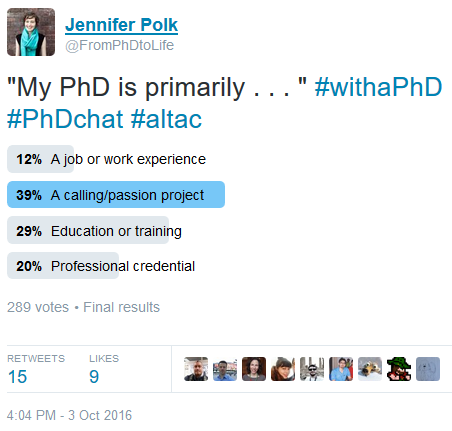

Earlier this month I posed a similar question on Twitter, in the form of a poll. “My PhD is primarily . . .” I prompted, and provided four possible responses (the maximum the platform allows): a job or work experience, a calling/passion project, education or training, and a professional credential. There were close to 300 votes, with nearly 40 percent choosing the second option: a calling/passion project.

If I were allowed more than four options, how about these, all of which come from people I know:

- A pathway to immigration

- A promise of a middle-class lifestyle

- A guaranteed income for the next five years

- A job with health and other benefits

In addition to the limited number of options, there’s another problem with the question, namely, that one’s take on one’s PhD changes over time. I know that over the course of my own doctorate — and in the years since I graduated — I’ve looked at the degree in different ways. And if I remove the word “primarily” from my question, I bet the write-in option “all of the above, and more” would prevail.

(When I asked the same question in a Facebook poll “education or training” came out on top — way on top. In both of my small polls, “professional credential” and “job or work experience” trailed behind.)

Why did I pose the question in the first place? In part it comes from reflecting on my own experience and recognizing the varied, often-overlapping realities involved in doing a doctoral degree. It comes in part from my frustration with debates about program changes where participants don’t make their assumptions clear. It comes from my frustration with how often and how easily the word “training” is applied to the PhD experience (and the postdoc, too). A PhD: why? Change: to what end? Training: for what? My frustrations reflect my own uncertainty about all this too.

PhD programs give grads flexibility. Or do they?

Part of me is happy to say a PhD is meant to be flexible, and that much is left to each individual student — in collaboration with advisors, in conversation with other scholars — to make of it what they will. Beyond the dissertation, there’s often flexibility in what and how to teach, whether and how to publish, if and how to engage as a subject expert in the wider world, and how to contribute to the academic community — by sitting on committees, organizing conferences, and doing a whole host of other tasks, large and small. In this model of doctoral experience, each student can craft a unique experience that aligns with their own strengths and goals.

All that sounds great. But I’m not sure that graduate programs do a good job of this, even when they buy into the vision. (I want to be wrong about this.) Advisors are busy; they have many other roles, some of which can conflict with providing genuine mentorship or coaching. Graduate students may have a tough time asserting themselves after years of, well, being students. (Googling “‘graduate school’ infantilizing” brings up nearly 20,000 results.) Self-reflection and -assessment aren’t built into most graduate programs. (I have heard great counter-examples, for what it’s worth.) Career management, when discussed at all, is assumed to mean launching an academic career as a faculty member, or at least a research job in industry. (Can a student genuinely explore career options while ensconced in a culture that implicitly rejects non-academic options?) That leaves a large number of students unsupported or ambivalently swept up in lackluster academic job market prep. What happened to individual agency? And what is a PhD, anyway?

There are many challenges and no easy answers.

When it does come down to individuals, knowing one’s personal purpose and goals is crucial. Graduate school itself may not be the best place to explore and get support for those goals, but one’s reflections and prioritizing can absolutely be applied to the grad experience. I see that with my clients.

What do you want or need your PhD to be?

I’m currently working with a client who’s mid-way through a doctorate. She intends to complete it, but is concerned about job opportunities afterward. In our work together so far, we’ve come up with ways for her to reflect on her values and priorities, take stock of her skills and strengths, and come up with possible ways to get experience and build skills that will make her more employable in future.

My client and I are on the same page in believing that she can build those skills in ways that tie into her academic work. For example, one of the fields she’s interested in is research communication. And so we talked about how she might blog about her research, sharing information and insights. What a great way to explore interesting findings that are tangential to her main argument! Blogging could prove invaluable to her academic work and provide proof of skills and expertise relevant to future employers. One example out of infinite possibilities.

While those of us inside and beyond the academy work on ways to make the PhD experience the best it can be, here’s to students — ideally in collaboration with advisors, other mentors, and members of their wider network — reflecting on their true goals and exploring relevant career options. And here’s to them finding ways of connecting those goals to their current work as graduate students. What is your PhD, anyway? Or better: What do you want or need it to be? How can you make it so? Now, what will you do?

what is a PhD? it is many things to the student, but it is one thing to the university – the end of their money milking relationship with the student.

I would agree with the poll results that a Ph.D. ought to be a passion project. While I made the decision to stop my academic career at the M.A., my drive entering graduate school was a passion for my field. My aspiration was to turn that passion into a career. But, once I saw the withering job market, the realities of publication races, and the uncertain future of the humanities, I was scared off. While my passion still thrives and I continue to consider taking on the PhD, I understand my passion would need to take a great leap hoping I will not experience the difficulties Jennifer mentioned above: busy supervisor or lack of mentorship (no to mention not finding an academic position). Additionally, the Ph.D. falls in a particular time in life where other life aspirations may come into a picture: starting a family or building a career with related skills that fall outside the scope of a Ph.D. The question then may become: when does one appropriately pursue a passion project?

A very interesting article. I completed my Ph.D. over 15 years ago. It was a passion; however, I kept going simply because I felt that I should. I’ve never regretted my Ph.D., and it has proven to be a useful degree because it trained me to think deeper about issues both historical and contemporary. In my current job as a high school teacher (yes, Ph.D.’s can teach high school), it helps me convey complexity to my students. I have a deeper grasp of my subject (history), and my students appreciate that I approach their questions in a scholarly fashion. I can model an approach for them and, hopefully, this will help them in the future. They also call me “Doc,” which I enjoy.