When I started teaching, my approach to undergraduate research closely echoed what I had experienced as an undergrad. I would assign students research papers, with the length and complexity varying by course level, and that was that. I thought of “research training” as being something that occurred mostly in graduate study and my approach to undergraduate research was focused on content knowledge and assessment, rather than skills training.

My thinking about undergraduate research training shifted considerably when I decided to make my first-year class part of my university’s First Year Research Experience Initiative (FYRE) program. Approaching undergraduate research assignments in terms of skills training expanded my creativity in designing assignments and led to a more engaging experience for my students.

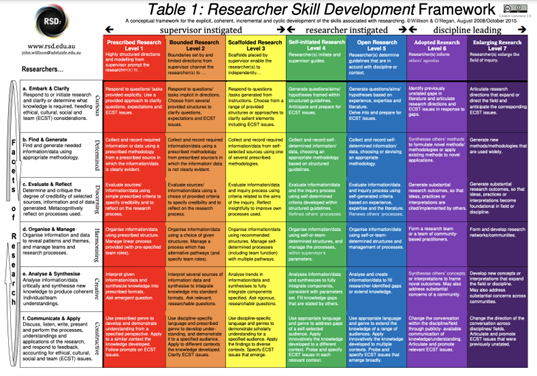

Understanding the continuum of research skills

In 2007, John Willison and Kerry O’Regan published their Research Skill Development (RSD) framework. This framework encompasses five levels of research skill development, ranging from low autonomy (prescribed research) to full autonomy (unbounded research). Over time this was supplemented by an expanded framework, referred to as the RSD7, that has seven levels of research skill development. As Dr. Willison and Femke Buisman-Pijlman explain, “The framework was extended to seven levels to bring in the unequivocally ‘capital R’ research, so that the whole university community would be on the same continuum, from a first-year student to a high-profile professor.”

The framework can be adapted to create rubrics that fit disciplinary contexts due to their general nature, and have been tested in several postsecondary settings, in fields such as accounting, biology, education, engineering and health sciences, as well as at levels from first-year to postgraduate. Reported benefits beyond skills training include increased student metacognition about research processes and strengthened research culture through the development of undergraduate research curricula.

Finding the right research autonomy level for your course

A strength of the framework is that it assists faculty in assessing the different research autonomy levels and student’s associated skills to help determine what is too much or too little to expect of them. As Mandy Fehr, coordinator of the University of Saskatchewan’s undergraduate research initiative, explained to me, “We want to think about what an appropriate skill progression looks like for the level of the course and the experiences that students bring into a course. It’s reasonable to build skills for first-year students towards a level two or three if they’ve previously only worked at a level one or maybe do not have any prior experience. Ideally, undergraduate students will reach level five by the end of their degree.”

How might you use the research framework in your teaching? Here are three ideas to consider:

- Use the framework to reflect on your approaches. In their recent blog post “Embedding Research, Artistic, and Scholarly Skills: A Step-by-Step Guide for Classroom Success”, Ms. Fehr and Aditi Garg (educational development specialist at the University of Saskatchewan) present a self-guided reflection exercise for faculty to generate ideas for embedding research skills into their courses.

- Use the framework to increase student metacognition of research skills. Share the framework with your students and have them self-assess their current research level, and/or assess your research assignments against the framework so that they can better understand the assignment’s purpose. As Ms. Fehr told me, “Students advance their research skills by building autonomy. Instructors can make research less scary by making it about skill development.”

- Use the framework to prompt discussions with colleagues. Working with your university’s teaching and learning professionals, use the framework to inform department-specific discussions about research skill development and progression over course levels.

Some examples of first-year research experiences

To return to my own experience with reimagining and innovating research assignments in my first-year political science classes, I experimented with several options:

- In one class, I had the students establish research questions that could be answered through a class survey. I then conducted the class survey and students analyzed the data to answer their research questions, presenting their results to their peers.

- In another class, I focused on researching an ongoing election. I had students write a short literature summary about a local campaign, a research question building from their literature summary and a research plan in which students identified one electoral constituency that they would follow during the election to answer their research question. They then wrote a research paper, using their case study research to answer their research questions and reflect on the literature.

- In a third class, I focused on the skill of working with Statistics Canada and Elections Canada data. Students selected two federal constituencies and used official statistics to complete a worksheet. I explicitly trained students in how to access and interpret these data. Students wrote up their observations about the two constituencies, identified a research question based on the data, and used literature and available data to answer their research questions.

For each of these first-year assignments, students were working in the first three levels of the research continuum. To supplement their work with reflection exercises, I had students complete three reflection questions to discuss with their peers and submit to me:

- “One thing I enjoyed about conducting this research was…”

- “One thing I found challenging about conducting this research was …”

- “One lesson I will take from this experience for future research projects is…”

My own experiences have convinced me that teaching students research skills from the get-go is a valuable exercise. I hope these ideas inspire your thinking about opportunities within your own courses.

Continuing the Skills Agenda conversation

How do you incorporate research skills training into your courses? Please let me know in the comments below. And for additional teaching, writing, and time management discussion, please check out my Substack blog, Academia Made Easier.

I look forward to hearing from you. Until next time, stay well, my colleagues.