When I decided to start explicitly building career skills training in my own classes, I struggled with the decision of which skills to include. Should I focus on a larger competency area like critical thinking and problem-solving? A more focused technical skill, like how to navigate and use official government statistics? What would help my students most, and what did I feel motivated to teach?

One challenge for getting started with skills training in university classes is that, outside professional disciplines like nursing, education, or engineering, the link between higher education and careers is rarely self-evident. University students graduate to go on to an array of careers that often are not clearly related to their disciplinary degree. Humanities majors can end up working in management or technology, science majors can end up working in sales. All students can benefit from skills training, but as faculty and instructors, knowing which skills to include in our classes can seem like a mystery.

So how can you get started? Here are three ideas to help you choose.

Identify your comfort level and intrinsic motivation

As faculty members and instructors, we may feel more confident teaching core content (facts and theories) than career skills. I felt this myself when I started considering explicit skill instruction: even though I had worked outside academia for 10 years before starting as a professor; I wasn’t “trained” to teach career skills per se.

Such uncertainty is fairly common. Looking specifically at Canadian political science doctoral programs, my co-investigators and I found that only one-third of faculty feel well-equipped to help students prepare for non-academic careers and only 20 percent of department chairs report that their faculty members are well equipped to help students with career preparation.

But the good news is you already have a solid foundation to start from. As faculty and instructors, we all have skill areas with which we are particularly comfortable: Writing, oral presentations, data analysis, problem identification, understanding and respecting diverse cultures, Argumentation, and project management. What are the skills that you have that help you succeed in your own work? Remember that sometimes our best skills are ones we don’t fully recognize in ourselves because they come so naturally to us. Build on these first, rather than feeling you need to pass on a skill to students that you are still struggling to master yourself.

Tapping into your areas of personal comfort makes the idea of skills training less intimidating and more natural. It also likely triggers your intrinsic motivation, building skills training into your teaching in the first place. I suspect you care about the skill areas that you are strong in, and that you believe that your students would benefit from having these skills as well. Chances are also good that you have taken time to develop these skills and have discovered some strategies and approaches along the way that you could share with your classes.

Ask your students what skills they wish to develop

In my experience, students appreciate the opportunity to provide input on classes and teaching. This spirit can be put to good use to help prompt your own thinking, particularly as you will be able to tie the idea of skills training to real students that you care about. Here are two easy ways to get this information from students.

- In a live class session, ask them, “In addition to increasing your understanding of [subject area], what skills would you like to develop or improve before the end of your program?”

- Use an anonymous class survey, either with your course learning management system’s survey tool or another software option such as Google Forms. You could use an open question such as I provide above or create closed questions. Here is a set of closed questions you may wish to adapt:

Please indicate your opinion regarding how important it is that you develop the following skills:

| By the completion of my program, I will have the ability to effectively: | Importance for me to develop this skill: | ||

| not important | somewhat important | very important | |

| Think critically | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Work collaboratively | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Communicate complex information to a variety of audiences in written form | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Communicate complex information to a variety of audiences orally | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Display understanding of Indigenous perspectives | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Work respectfully with individuals of different gender, culture, and identities | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Exercise integrity and ethical behaviour | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| Manage a project from start to completion | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| [technical skill relevant to field of study] | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

| [technical skill relevant to field of study] | ❏ | ❏ | ❏ |

As I discussed in last month’s column, my personal motivation for skills training is that I see it as helping my students meet their goals. If you share this motivation, asking students directly will open exciting discussions and prompt your thinking in new ways. (An important note: if you anticipate that you may wish to use student’s’ feedback for future research rather than simply to inform your teaching, be sure to touch base with your research ethics office.)

Pick one – just one – skill to focus on for any given class

While there are many skills you may wish to focus on, both you and your students have numerous competing pressures on your time and attention. Selecting a single skill to teach and develop in a course is sufficient to add value.

You may wish to focus on different skills across your classes. This has been my own approach in teaching political science:

- In my 100-level class, an introduction to Canadian politics, as part of my university’s First Year Research Experience program, I focused on the skill of working with official statistics from Statistics Canada and Elections Canada.

- In one of my 200-level classes, I opted to focus on a broad competency, critical thinking.

- In another of my 200-level classes, research methods, I taught students how to complete research ethics review applications.

- In one of my 300-level courses, public policy analysis, I incorporated the skill of writing government briefing notes; in another offering of this same class, I had students work on the skill of writing for public audiences through an opinion-editorial.

- In my graduate class, I incorporated teaching skills, requiring students to take on teaching a course topic to their peers.

Changing the skill training I am focused on suits my personality and keeps me excited about the possibilities.

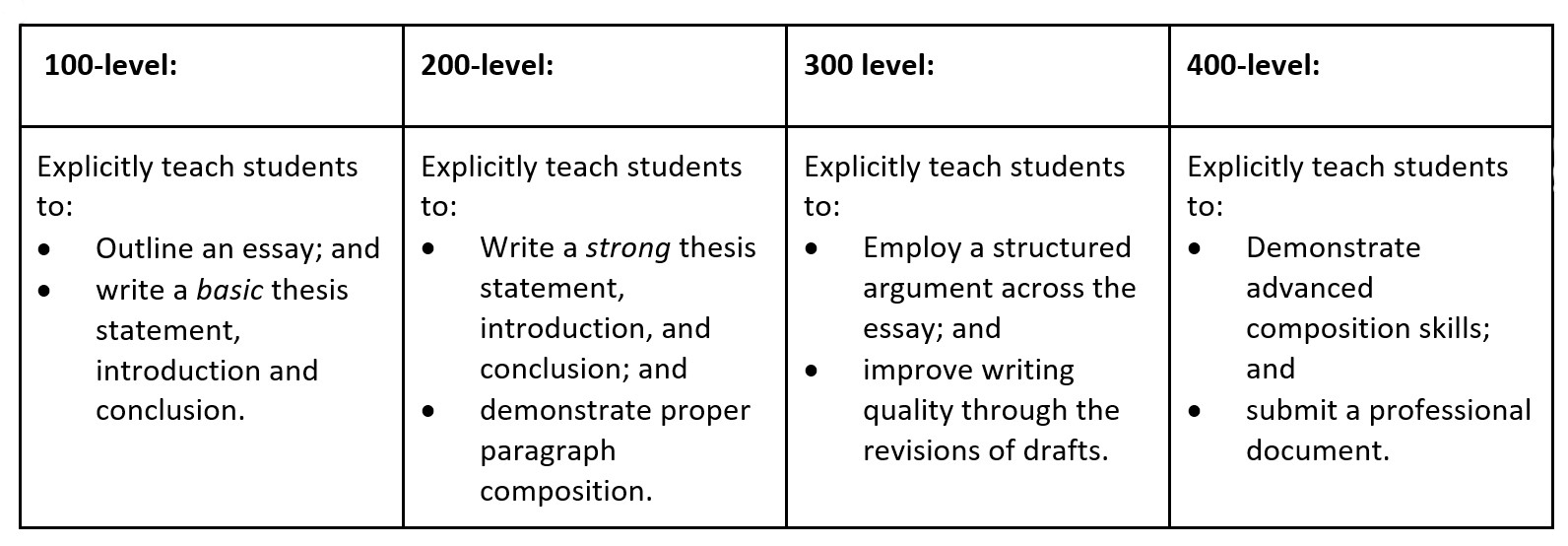

Alternatively, if you are a bit more focused than I am, you may wish to focus on a single competency area across all of your classes, adapting how you go about the skill training by the course level. For example, if you aim to teach written communication skills, you might decide to focus on essay structure and then divide skills instruction as follows:

Continuing the #SkillsAgenda conversation

What career skill(s) do you feel most drawn to teaching? Please let me know by connecting with me on Twitter at @loleen_berdahl and sharing your thoughts using the hashtag #SkillsAgenda, or by using the comments section for this article.

I am excited to hear from you. Until next time, stay well, my colleagues.