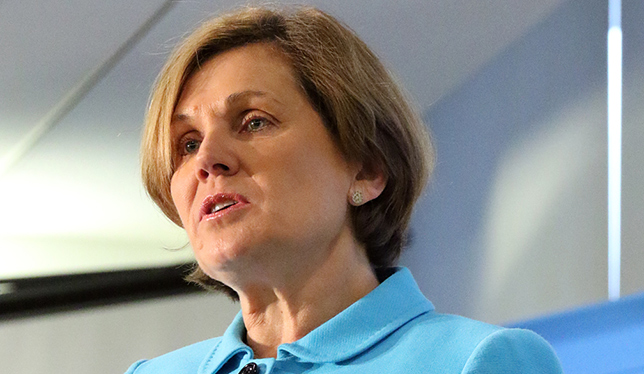

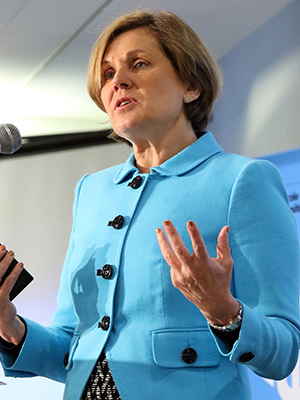

membership meetings. Photo by Mike Pinder.

Though they’re on opposite sides of the planet, Canada and Australia have much in common when it comes to the higher education sector. Universities in both countries are focused on increasing international student mobility and are also working alongside government mandates to strengthen innovation performance. It was on these two issues which Belinda Robinson, CEO of Universities Australia, was invited to speak at Universities Canada’s fall membership meeting in Ottawa in October. University Affairs took the opportunity to sit down with her to discuss what Canada might be able to learn from the situation in Australia.

University Affairs: What would you say are some of the key challenges facing Australia’s universities today?

Belinda Robinson: I think at the highest level, one of our key challenges is the need for a policy setting that enables universities to position Australia to make the transition from a resource-based economy to a new, innovation-driven economy. Within that, another challenge is to ensure that we have a much more stable policy environment and more long-term, predictable funding for teaching, learning and research. We’ve been discussing higher education reforms now for two-and-a-half years, and this is impacting the ability of universities to plan from one year to the next.

UA: Australia’s universities have been very successful in attracting international students and, in recent years, encouraging more Australian students to study abroad. What accounts for that success?

BR: We have a strong track record in international education. We’ve been doing international education for over four decades, such that it is now our third-largest export industry, valued at around $20 billion ($20.4 billion Cdn). It’s also our largest services export industry.

In terms of outbound mobility, we do have a long way to go. We haven’t been good at encouraging students to study abroad. We started from a very low base. We’re now entering this third wave of international education where the focus is very much on encouraging Australian students – particularly undergraduate students – to incorporate an overseas study experience as part of their degrees. A number of things have started to prove very successful.

Probably the most success can be attributed to the introduction of a program called the New Colombo Plan. This has had the personal backing and support of our foreign affairs minister, Julie Bishop, who was personally involved and personally committed to the development of this program, in fact, when she was part of the opposition party. So when they came into government, the scheme was introduced very quickly. One of the really key components of the New Colombo Plan is not just providing students with a study experience, but it also provides the mentorship and an internship opportunity as well. I think the program has been successful – not just in its own right – but also in creating a halo effect around the benefits of studying abroad.

UA: As you know, international students face many challenges during their studies and also after they graduate. What should universities be doing to ensure they have a rewarding student experience?

BR: We know that many students are looking for an intercultural experience, and that’s a challenge for us. Universities are very focused on trying to provide mechanisms for international students in particular to intermingle with domestic students and international students from nations other than their own, with varying degrees of success. Most of our students come from Asia and the tendency – like we would if we were studying overseas – is you feel safer and more comfortable when you’re with those from your own cultural background. So there’s a lot of emphasis on finding opportunities for students to engage more with others. Safety on campus of course is another key issue, so universities put a lot of effort into ensuring that our international students have access to safe accommodation options.

In terms of the opportunities for international students once they’ve completed their study, Australia has recently introduced what’s called post-study work rights. So those studying an undergraduate degree are able to stay on in Australia and work for a year, those studying a master’s program are able to stay on two years, and those studying a PhD are able to stay on for three years. The challenge is trying to expand the employment opportunities for those students, because what we’re finding is that it’s not necessarily easy for them to find work. The Australian government released an international education strategy earlier this year with a goal of increasing the market share of Australia as a provider of international education, and one of the key elements will be around working with employers to expand the number of opportunities for international students.

UA: During your visit here you gave a speech about innovation, which is a top priority identified by our federal government. What do you see as the role for universities in fostering innovation?

BR: I think there are three key roles for the university. The first is through the research that universities undertake. In Australia, universities conduct the majority of publicly funded research, and it’s this research, often, that leads to the innovation that’s required to develop new products, new industries and new ways of doing things. We also have a government that has put a very high priority on increasing the level of innovation that occurs in Australia, because internationally we don’t perform particularly well around innovation. Universities also play a role in translating their research into products and services for the nation through spin-off companies and through their own activities. But, thirdly, they play a critical role through the graduates they produce and by ensuring that these graduates have the skills and the knowledge that they need to be able to transform our industrial structure and achieve economic diversification.

UA: It can be hard to pin down what “innovation” means, but there is a sense in Canada that it revolves around science and technology – do the humanities and social sciences have a role to play, too?

BR: I think that’s the same in Australia, but there has been a lot of people working very hard to make sure that it’s well understood that innovation is not just about science – it’s about new ways of doing things for the benefit of the nation. And I think we are starting to get a greater acknowledgement that we really can’t have innovation without the involvement or integration of the social sciences and humanities, and the arts.

UA: Do you have any last thoughts on your visit – perhaps similarities or differences you’ve observed between our higher education sectors?

BR: The key difference that I’ve observed is that while most of our universities are established on state-based legislation, the funding for universities primarily comes from the federal government. So, much of the work we do is around how universities are funded – the relative mix between the student contribution and the public contribution, the student loan scheme and how it is designed. In addition, we work on all the sorts of issues Universities Canada works on in terms of ensuring long-term, sustainable investment in research infrastructure, research more broadly, and in international education and encouraging outbound mobility. Those issues we have a great deal in common with. And, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, but nevertheless it’s been very clear to me that we do share many of the same public policy challenges.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.