Margaret Somerville and Judy Rebick occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum, but they’re on the same page in assessing the role of a public intellectual. Both adamantly promote the value of public debate and the need for debate to go beyond the predictable sound bite to a more thoughtful and extended conversation. Like many public intellectuals, they are reluctant to take on the title themselves but agree that the role is essential.

Ms. Rebick, a progressive activist who was president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, founder of the leftist online magazine rabble.ca and a regular on CBC Radio’s Q with Jian Ghomeshi, worries that Canada is in a state of decline when it comes to public debate. That’s partly due, she says, to a dearth of forums for lengthy discussion on topics of national importance. “We need more public intellectuals. We have very little debate now, and it’s all ‘gotcha’ debate that’s not about ideas.”

While the media do seek out commentary, they often round up the usual suspects – who are not always a diverse bunch – and then set up an intentionally polarized encounter where participants advocate one side, rather than explore an issue. “The public intellectual doesn’t fall into that trap,” she says. “You’re not just fighting for a cause. You’re also wanting to explore the issues.”

Dr. Somerville as well feels there’s a need to make time for more exploratory debate. An ethicist and professor in the faculties of law and medicine at McGill University, she often expresses strong opinions on topical issues (she opposes euthanasia and abortion). “We should try to start from where we agree rather than where we disagree. That gives a different moral tone to our discussions,” she advises. “For instance, with regards to euthanasia, nobody thinks people should be left in pain and suffering. So we agree on that. Where we disagree is what is acceptable to do to deal with that situation.”

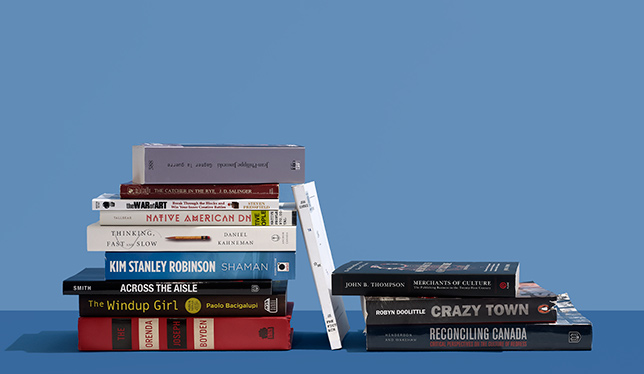

Both Dr. Somerville and Ms. Rebick recently had occasion to think more closely about the topic of public intellectuals. Ms. Rebick has been invited to speak at a conference called “Discourse Dynamics: Canadian Women as Public Intellectuals” to be held at Mount Allison University in mid-October, and Dr. Somerville contributed to a recent essay collection called The Public Intellectual in Canada. Edited by University of Toronto political science professor Nelson Wiseman, the collection features essays from many vantages, including academic Stephen Clarkson, retired senator Hugh Segal (now master of Massey College at U of T), political insider Tom Flanagan and journalist Doug Saunders. The writers look at the topic from the lens of gender, aboriginal concerns and the media, among other perspectives.

In a chapter about public intellectuals of the 20th century, Dr. Wiseman says Stephen Leacock, Marshall McLuhan and Harold Innis stand out as strong examples. He muses on the predictable preoccupations of a Canadian intellectual. “Canadians struggle with identity in a way that Russians, French, British and Americans don’t,” says Dr. Wiseman. As a result, Canadian public intellectuals write about “how they would like to define the country.” For those few who have transcended national boundaries to attain an international profile – he names Margaret Atwood, David Suzuki and Denys Arcand – their opinions can provide an unofficial lens into Canada.

Atwood, Arcand, Suzuki … One of the fun aspects of writing about this topic is engaging everyone you know in the game of “name a public intellectual.” Partly because you’ll inevitably leave out someone important (Irshad Manji, Stephen Lewis, John Ralston Saul) or include someone that others don’t agree with (Naomi Klein, Don Tapscott, Conrad Black), it’s the world’s nerdiest party game.

The definition itself is nebulous. Many who try to define the term name similar characteristics. “[Public intellectuals] favour capturing a public culture in a world of ever-increasing hyperspecialization and an increasingly fragmented public space, communicating their ideas on an array of public issues to a wider audience beyond their narrow fraternity of peers,” writes Dr. Wiseman. Or, more simply, in Margaret MacMillan’s words: “[Stephen] Leacock was made for the lecture stage. He was a man of many and strong opinions on the big issues of the day” (Extraordinary Canadians: Stephen Leacock, 2009).

Some academics are reluctant to accept the label, in part because it can be seen in a negative light with connotations of elitism. “I felt embarrassed because it sounds pretentious,” says Dr. Somerville. “But if it simply means that you work in public, which I do, and the Oxford Dictionary said it means you’re trying to explain things to people, then I thought, well, that’s what I am.”

Thomas Homer-Dixon, too, says he’s “not a big fan of this label,” partly because of its mixed connotations. “Anyone who engages in public debate as a scholar is at risk of being labelled not a serious scholar, someone who is diverting their attention and resources away from research and publicly seeking personal aggrandizement,” says Dr. Homer-Dixon, chair of the Centre for International Governance Innovation of Global Systems at the Balsillie School of International Affairs and professor in the University of Waterloo’s faculty of the environment.

He says the rigid rules of academia mean he would probably discourage pre-tenured academics from public engagement, and that frustrates him as well. “A pejorative connotation has discouraged many scholars and academics who might [otherwise] contribute a lot to our conversation surrounding critical public policy matters, from health care to climate change. It discourages people from participating at a time when public issues are more complicated and ethically fraught, more requiring of diverse voices than ever before.”

When academics “evacuate the public space,” it can have serious consequences, he says. “You leave that conversation to people with strong vested interests … and that’s not healthy for democracy.” He would like senior university administrators to recognize “that creating this space and opportunity for scholars to engage in the public sphere is really important for the health of Canadian society.”

Some observers of the decline in the state of public intellectuals also point to the growing tendency of academia to turn out narrowly specialized scholars who aren’t able to comment on a broad range of topics in the media. In his 2001 book Public Intellectuals: A Study in Decline, the U.S. jurist and economist Richard Posner looked at how narrowed specialization collided with significant media growth to create a perfect storm: increased demand for public commentators met by a supply incapable of satisfying it. Now, more than a dozen years later, a headline over a New York Times column by Nicholas Kristof declares: “Professors We Need You!” But the column says that “a basic challenge is that PhD programs have fostered a culture that glorifies arcane unintelligibility while disdaining impact and audience.”

Dr. Wiseman notes that a rise in levels of education and growth of media choices has translated to a public less deferential to authority and so less willing to accept the opinion of so-called experts. The media add to that cynicism when, as others point out, outlets cut short real debate in favour of superficial punditry.

So why do it? Despite his qualms, Dr. Homer-Dixon has written many op-eds and several successful trade books, including his award-winning The Ingenuity Gap. In his case, it’s for the most personal of reasons: “I have two little kids, an eight-year-old and a five-year-old,” he says, “and I’m concerned about their future.”

A similar impulse prompts Wade Davis, a long-time independent scholar and now a professor at the University of British Columbia, to speak out. Dr. Davis has published many bestsellers, saying he felt compelled to share publicly what he’d learned in his combined fields of biology and anthropology. “The issues the world is facing in those two disciplines are too important to be shared only within the insular culture of the academy,” he says.

Conveying that information to the public also goes a long way to maintaining relevance. “This is a constant dilemma,” says Dr. Davis. “How can we expect the public at large to support policies that address issues like climate change when we failed utterly to explain to them not just that issue but the very sense of what science is?”

Jim Davies, a young associate professor of cognitive science at Carleton University, has entered the public realm with a blog for Psychology Today magazine, TED talks, and a trade book (Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe) that made a media splash when it was released this summer. He believes that academics have an obligation as public employees. “For me to get to this point required 25 years of education, so really the public has already paid me an enormous amount of money,” says Dr. Davies. “They’ve invested very heavily and I feel a great responsibility to make it worth it.”

The media are also obligated to inform the public responsibly, given their role as catalyst and gatekeeper. Ms. Rebick, who has stepped back from radio and television appearances, says the media need to keep replenishing the opinion pool of public intellectuals. “I haven’t been actively involved in the women’s movement for 20 years, but still when they want a perspective of a feminist they call me. It makes it seem like there’s no young feminists and there are lots of young feminists.”

The lack of media platforms in Canada may also be an issue, says Dr. Homer-Dixon. “The competition to get something on the op-ed page of the Globe and Mail is probably about as tough as it is for the New York Times because you’ve got so few outlets here to express your views.” Meanwhile, new media – with their incessant demands for online content – are changing and fragmenting the landscape.

But, for aspiring public intellectuals democratization can only be a good thing, says Christl Verduyn, professor of English and Canadian studies at Mount Allison, who is co-organizing the conference on women public intellectuals. The conference is “not just for women,” she says, “but for groups that feel they don’t command the public space. I think there’s a lot of exploration and work to do in this area.”

So for those who, despite the odds, still aspire to contribute to the public space, do these veterans have any practical advice?

Ms. Rebick says she learned how to speak in public by observing others. “For example, I really studied Ronald Reagan. I hated his politics, but I watched what he did. I learned that you can say radical things or be outside the accepted norm if you say it with humour, warmth and care.” She also counsels newcomers to public engagement to be themselves.

The academics in the crowd have advice for their institutions and their students, as well. Dr. Davis says that one of the most supportive things his professors did to aid his public career was to get out of the way. “My professor never helped me, but he did something much more important: create an atmosphere where he did not see the acquisition of those skills as a threat to my core academic mission but a complement to it.”

Now that he’s joined UBC, Dr. Davis vows to do the same for his own students. “I ask, how many of you are taking creative writing, media training, public speaking, photography, cinematography? If you want to be effective as an anthropologist, you will always be a storyteller, so you’d better find a way to tell stories and do it well.”