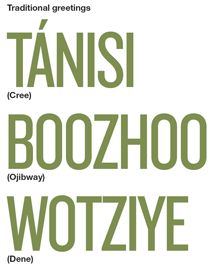

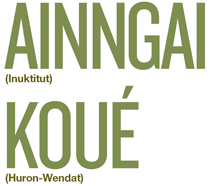

It was shortly before seven o’clock on a Monday night last March when the participants in a unique experiment in Canadian culture filed into a classroom on the tiny Huron reserve of Wendake in the north end of Quebec City. As they entered, they greeted each other with traditional words of welcome – “koué” or “Ndio” – in their ancestral tongue, Wendat. Once settled, the 16 students (an equal number of men and women between the ages of 15 and 76) spent the next two hours trying to learn and converse in a language that has not been heard or spoken on Earth for more than a century.

Welcome to the Yawenda project, a federally funded, million-dollar effort that aims to revive the use of the Huron-Wendat language on the Wendake reserve. Launched in August 2007, the five-year project entered a crucial stage this past spring when two once-weekly courses began with about 40 students. A third course started in April. The project also provides for teacher training and the creation of instruction materials to help teach Huron-Wendat to preschoolers and elementary school students.

“Reviving a dead language is a daunting task,” says Louis-Jacques Dorais, an anthropologist at nearby Université Laval and the lead researcher in the project. “But there is a lot of effort and desire among the Huron to make this project succeed.”

Similar sentiments are driving several language revitalization projects in aboriginal communities across Canada, and a small but growing number of academics from various fields are playing major roles in many of them. At stake, experts say, is the fate of the 52 distinct indigenous languages that help to make Canada one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world.

“All of them are endangered,” says Lorna Williams, a member of the Lil’wat First Nation and holder of the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Knowledge and Learning at University of Victoria, where she is an assistant professor in the department of education. “No exceptions.”

According to Dr. Williams, several major studies show the dire straits of Canada’s indigenous languages. The most recent was a survey in Native communities across British Columbia. Carried out by the First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council, a provincial agency that provides funding for language and cultural projects (and also advised Quebec’s Yawenda project), the survey found that of the 32 indigenous languages in B.C., three have no known living speakers. It also revealed that a meagre five percent of the 100,000 aboriginal people in B.C. are fluent in an ancestral tongue, and most of them are over 65.

Those results resemble the findings of a much bigger study carried out a decade ago by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Its report in 2002 said that more than a dozen aboriginal languages in Canada were either extinct or were on the verge of becoming so. That prompted the then Liberal government to promise $172 million in spending over 11 years to help save aboriginal languages.

Part of that money was used to create a task force to delve into the issue. Among other things, it found that even so-called “viable” language groups – notably Cree, Ojibway and Inuktitut, which each have more than 20,000 speakers – “may be flourishing in some regions and be in a critical state in others.” Regardless, all of the languages, the task force concluded, “are losing ground and are endangered.”

The funds earmarked by the federal government for aboriginal language preservation were cut in 2007. Currently, the Department of Canadian Heritage manages an Aboriginal Languages Initiative which provides about $5 million in annual funding to support community-based language projects.

“There is an urgent need to act,” says Dr. Williams, who blames Canada’s indigenous language situation on colonization, urbanization and, above all, a hellish residential school system that forcibly uprooted thousands of Native children – her included – and robbed them of their ability to communicate in their mother tongues. “We don’t have much time left to document the knowledge of these languages [and] to hear their beauty.”

The big question, of course, is how. Like the task force, which made two dozen recommendations on how to strengthen indigenous languages, the B.C. report puts a premium on projects that encourage their use at both the family and community levels. Notably, it recommends a quintupling in the province of preschool language immersion “nests” from the current eight to 42 within three years. These apprentice programs pair young English-speaking Native families with community elders who speak the language with a goal of raising children in bilingual environments – or nests – that will continue on through school and into adulthood.

“Reconnecting generations is the key,” says Dr. Williams, who founded an ongoing language teaching program in her home community of Mont Currie, near the modern-day Whistler Blackcomb ski resort, in 1972. “You can’t rely on school-only programs.”

Christine Schreyer agrees. An assistant professor of anthropology at the University of British Columbia, she has been working for several years on collaborative research projects dealing with land claims and language with two different Native communities: the Loon River Cree First Nation, in north-central Alberta, and the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in Northern B.C., close to the Yukon border.

Both “tend to see language as a natural resource, like land,” says Dr. Schreyer, who has created a Tlingit-language board game and an eight-book series of Cree stories. She is also involved with a Tglingit dance group that she accompanied to the Winter Olympics in Vancouver in February. The dance group “teaches people the language by performing the songs of their ancestors,” says Dr. Schreyer. The performances also teach how to follow cultural protocols and the importance of traditional regalia, she says. “Community members need to be interested and see value in their language in order to use it.”

Adding to the challenge of protecting and preserving aboriginal languages are the myriad unique realities and challenges that every Native community across Canada faces – from band status (which dictates available resources) and geographic location to educational infrastructure and social cohesion. “It’s a very complicated situation,” says Alana Johns.

A linguistics professor at the University of Toronto who loves complex words, Dr. Johns says she hit the jackpot when she discovered Inuktitut, a language in which some words can be an entire sentence long. She has spearheaded several research projects on Inuktitut grammar and trained many Inuit to be language teachers.

Despite being one of the healthiest indigenous languages in Canada –according to the 2006 census, 32,200 Inuit, or two-thirds of their population, declared Inuktitut as their mother tongue – numerous factors pose a long-term danger to the continued everyday use of the language in many communities, says Dr. Johns.

These include the relentless development of resources in the North, the accompanying migration of non-Inuit people into the region and an increase in Inuit working for non-Inuit companies. “It’s already a problem in some places along the Mackenzie River valley,” she says. “I liken it to little lights going off across the North.”

Though encouraged by the advent of the Internet, which reduces the need for high-priced travel to and around the North, and the fact that many Inuit are chatting in text messages in Inuktitut, Dr. Johns says more is needed from all levels of government in Canada – and from Canadian universities. She noted, for example, that U of T offers three-year degree programs in Russian and German, but offers only a few courses in three major indigenous languages through its aboriginal studies program.

“We could be doing more,” she says, but adds, “It’s important that we continue building on what we have and encourage the many motivated individuals who are working hard to protect and preserve their languages.”

It was precisely those kinds of people who approached Laval’s Dr. Dorais and asked him to support the embryonic language revitalization project that eventually became Yawenda – a Wendat word that means “giving voice.”

“I was very skeptical about it at first,” says Dr. Dorais, who nevertheless wrote a 50-page letter of intent, which was accepted, to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

The traditional homeland of the Huron-Wendat nation is in Ontario’s southern Georgian Bay region. Weakened by war and disease, they were overrun and destroyed by their Iroquoian cousins in 1649. Many fled west, eventually ending up on reserves in the United States. Several hundred others who converted to Christianity followed their French allies back to Quebec City, which they have since called home.

According to Dr. Dorais, the Hurons were highly sociable and integrated readily into the surrounding community. “They were in daily contact with French people and there was a lot of intermarriage,” he says. “Eventually they lost their language.” The last known speakers of the Huron-Wendat language likely died in the 1870s.

Since the Yawenda project began, however, Dr. Dorais says he has been impressed by the desire of reserve residents to resurrect their language. That has made him a believer in the long-term chances of the project, which will have to become self-sufficient or find alternative funding when federal funds end. “The Wendat people are survivors,” he says. “I wouldn’t bet against them.”

There is a need to preserve culture in it’s truest form, while it is still possible. I am a believer in Heritage and History. We, can, make a difference, a difference, together.

We need absolutely to view indigenous languages as a natural resource and a critical tool to regenerate a healthy communal fabric of meaning and belonging.

Universities also have a role to play. By teaching more indigenous languages, we can raise awareness in the general population around the specificity of indigenous culture.

All Canadians, not just aboriginal Canadians, will be greatly impoverished if indigenous languages are allowed to perish.

Language requires communities to understand and believe in the value of their own language, connect it to your foundational culture and family. Institutions do not understand what this means. Anyone can provide a language course and teach languages at the schools but…….how will it continue and be spoken in the community. There is still something missing….the connection. Deanna

First Nations languages will continue only as long as the individuals within that language group/community value the language enough to actively teach it to others. Languages all over the world become extinct every year so if we want them to continue to be viable we have to actively support them. The elders in any First Nations community are usually the resource that needs to be tapped into because they are the individuals who remember the language of their forefathers. A language archive of First Nations languages would be one way of ensuring a language did not become extinct but who would fund it and administer it?

When we consider that the English and French language provisions of the Constitution are founded on the prejudiced recommendations of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, what we ought to do is establish a new Royal Commission on language to study the impact of Official Bilingualism on indigenous peoples, especially in light of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

It’s easy for monolingual English-speakers and French-speakers to just nonchalantly say indigenous peoples should just work harder at their languages while also having to navigate a Constitutionally-imposed Anglo-French market.