It’s 8:40 a.m. on May 26, 2020, the day after the murder of George Floyd, and I’m in a virtual breakout room with a Black student who is crying in emotional pain. I listen attentively as she teaches me about this critical historical moment and its relationship to her lived experience. My computer is filled with images of police brutality and I’m trying to find words to quell my own rage against a system that kills Black people so that I can focus on the woman in front of me. What can I possibly say or do right now when we are two squares on a screen? I hear the truth and wisdom in her crying, and I listen carefully to understand how I can support her. I ask her if she wants me to raise Floyd’s murder with other class members during our opening circle.

I’m a professor of professional practice, with my primary responsibility to direct Simon Fraser University’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue. In May and June 2020, I also co-taught a seven-week summer course for SFU’s Semester in Dialogue called Democracy: The Next Frontier.

The Semester in Dialogue class provides 20 students with a semester-long, cohort-based experiential learning opportunity, eight hours a day, five days a week for seven weeks during summer semesters, and for 13 weeks in the fall and winter terms. Students love the program; it’s one of the top-ranked classes at SFU, year-after-year, since its launch in 2002.

Students are challenged to take responsibility for their own learning, developing skills and competencies that serve them in their future endeavors. They are introduced to and host thought leaders on the front lines of whatever issue is being explored that semester, work in small groups to propose solutions or ideas to address local concerns, and challenge themselves through skills-building workshops on topics such as how to host a dialogue, public speaking, and writing an opinion editorial or policy brief. It’s a deeply interactive class where students learn as much from their peers as they do from their professors or thought leaders.

The sudden shift to virtual learning

On March 16, 2020, I learned that I would have to deliver this signature program fully online. SFU, like most universities, had suddenly shifted to virtual teaching. I was worried, doubting that the program could be shifted to virtual mode. Dialogue and social interaction are the underpinnings of our program; I couldn’t conceive how students could build trust when they couldn’t interact in person. How might group work be organized online? How do you replicate a retreat within a virtual setting?

My co-instructor Daniel Savas was equally concerned. While he had taught graduate students for years, he hadn’t taught in the Semester in Dialogue, and the sheer volume of student contact hours was daunting enough. We had spent over 100 hours designing the course over the summer and fall months pre-pandemic. He had gone on sabbatical to Asia in the winter and when he returned in April on one of the last international flights out of Sri Lanka, he was presented with a very different academic reality.

After consulting with students from the spring cohort who had started their semester in person and finished online, I was feeling deflated. Their advice: don’t do it. “It will be a horrible experience for the students and it will be alienating,” said one student. “COVID-19 has created enough upset. You can’t expect students to handle such an intense 100 percent online experience,” said another. And after attending a few online seminars myself in March, I started to agree with them. These experiences were alienating and I wondered how we could possibly build the necessary trust among students to meet the unique attributes of the Semester in Dialogue experience.

But we had a full cohort of 20 students who had registered for the class, 35 thought leaders who agreed to participate, and a university expectation that we would deliver the course online. So Daniel and I set to work redesigning the class to a fully online experience, including a retreat that was originally intended to be hosted in person at a camp on nearby Gambier Island.

Every hour had to be reconsidered. We had to find ways of creating community immediately and ensure we balanced the energy of the class with on- and off-screen activities. We had to curate new spaces for students to learn independently and as a class. And, we had to ponder new forms of engagement in the virtual space.

A community quickly evolves

Daniel created a mural for students to introduce themselves through words and pictures. We made our own introductions and shared stories about ourselves through gifs and personal photos. Not to be outdone, students populated the mural with fun, interesting and creative responses to the open-ended questions we asked them.

To our surprise, the online classroom quickly evolved into a real community for many of the students. Daniel and I would arrive each morning to our Zoom link 30 minutes early to go over any final adjustments to the day, and around 8:45 students would start to join in. At 8:55 we would choose a song to open the day. After the third day, the song choice started to rotate between students and the selections ranged from 1960s protest songs from their parents’ time to 2020 releases that spoke to the daily realities students were facing with COVID-19.

Music became a rallying point for the class. A student stepped up to play class DJ, ensuring breaks were spiced up with the latest Beyoncé or indie release. These five-minute dance parties injected energy before an afternoon online session.

At the beginning of the semester, we asked the class to set the terms of engagement for how we should behave and interact online. Students indicated that they wanted cameras on if we were in a dialogue together or if we were hosting a guest to the class, which was most days. If students needed a health break or were feeling eyestrain, it was okay for cameras to be off, but only if the students let others know through a note on the chat wall.

The design of the class was highly interactive. We kept presentations to no more than 10 minutes before injecting some kind of interactive component. We limited the use of the shared screen function and ensured there was a lead facilitator so students knew who to reference for guidance.

Each student was tasked with designing and hosting a session with a thought-leader. These sessions were between 90 and 150 minutes in length, and involved prepping the class, introducing the speakers, designing the dialogue components and facilitating the session and debrief. We had many thought leaders join us, including former Reform Party leader Preston Manning, Independent MP Jody Wilson-Reybould, and former Vancouver City Councillor Andrea Reimer.

Students were also assigned to small teams to design, develop and implement an engagement strategy with a target community of young people to determine how they were affected by the pandemic. The teams then developed policies that they pitched to elected members of parliament, provincial MLAs, mayors and community leaders, and received feedback in a final online showcase that was open to family, friends and other community guests. The small-group projects were powerful, with each group profiling a different segment of the population, including front line workers, refugee students, youth-at-risk and postsecondary students.

The Instagram stories generated by one of the groups caught the attention of CBC and CTV’s Breakfast Television, and resulted in feature profiles with two students and a spotlight story on the SFU news site. Some of the students from this group were so inspired that they formed an organization to continue working with youth called Together Tomorrow after the semester was over.

The outside world intervenes

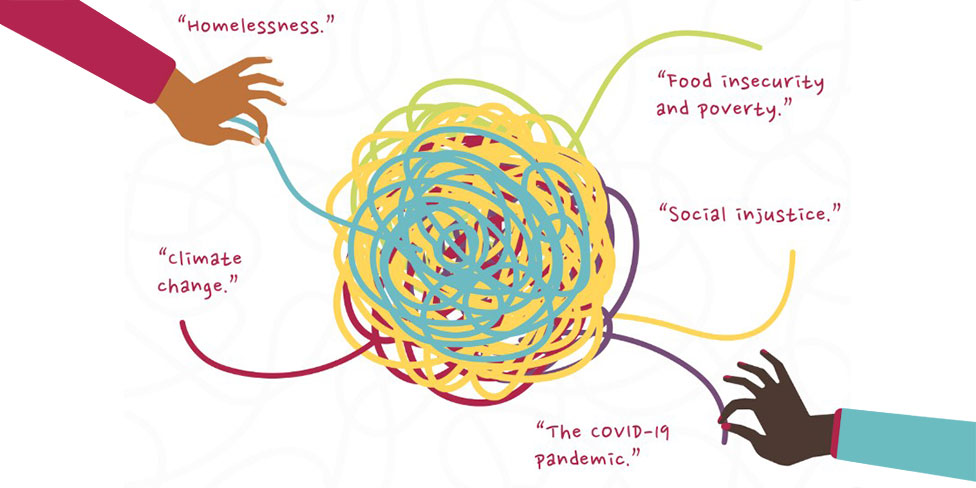

If the stresses of teaching online through the pandemic were not enough, the students of Democracy: The Next Frontier also experienced the Hong Kong protests, where at least two students had family, and the surge of the Black Lives Matters movement. The killing of George Floyd brought racial equity, decolonization and justice to the foreground, and had a profound impact on the dynamics and dialogue within the online class.

One of the most difficult moments for me in teaching the class was that morning following the killing of George Floyd. At 9 a.m., the Black student and I left the breakout room and joined the full class. Tracy Chapman was playing in the background.

The morning circle was sobering as each student took their turn to describe how they were doing. The disturbing scenes invading our screens burst our classroom bubble. There were some students who were angry, others confused about the situation and still others oblivious to the protests erupting across the U.S.

Up to this point our class had existed in a virtual otherworld, many students seeing the semester as the highlight of their day, looking forward to seeing their classmates each morning. It had been a lifeline, a way out of the intense isolation they were feeling due to COVID-19, and they were loving the online sense of community they had built.

But no physical or online community can or should be insulated from the ebbs and flows of real life. The role of institutions to examine racist, White supremist attitudes, policies and procedures became a topic of dialogue within the class. The class needed space to process what it meant to be in this historical moment together – to comprehend centuries of Black oppression, the impact of colonization, their implicit and explicit role in maintaining institutionalized racism, and what role they could play as allies and advocates for change.

We two white, privileged instructors fumbled our way forward through these difficult discussions. Despite our desire to keep up with the course design, the issues of inclusion and diversity erupting outside the classroom emerged in morning check-ins, conversations with thought leaders and dialogue debriefs. It also emerged in the way students related to each other off-screen, as some participated in protests together, provided comfort to those who needed it or devoted hours to learning more about the issues.

Balancing students’ anxiety and mental health needs was challenging, but a priority for Daniel and me as we navigated through the final weeks of the course. Creating a community of peer support, providing individualized coaching and accessing SFU institutional supports were key.

Wrapping up

On the closing day of the semester, after students opened the letters they had sent to themselves on the first day of class, evaluated the course and reflected on their learnings, we closed with a circle and a written gratitude exercise. In preparation for this exercise for an in-person class, we would normally distribute a personalized envelope and 22 pieces of paper, one for each student and each instructor. We ask students to write a sentence of gratitude to each person – something big or small that was positive about their impact on the individual or class. We then circulate and fill the envelopes so that when the person returns home that evening, they have a gift from their class to open.

In a virtual classroom this meant sending personal emails to 22 people. Those emails and the following instructor evaluations were rich and raw. They gave me insight into what it is like to be a student living through this pandemic, to feel isolated and to break through that isolation with an intense learning experience.

The messages revealed how empowered some students felt by the small-group work and how they intended to advance their findings beyond the class end date. And, for most students, those letters described how much their views of democracy shifted – from disengaged cynic to democracy activists. I smiled when two students told me that the class had inspired them to run for public office and three others indicated that they wanted to start their own democracy initiatives.

Teaching any full-time, experiential learning program like the Semester in Dialogue is demanding. But teaching during a pandemic and the unrest brought a whole new level of challenge. Teaching virtually also opened my eyes to how much concentration and effort it takes to hold the space for difficult conversations, and it made me recognize how much I depended on Daniel, as co-instructor, to balance the energy and support in the classroom. It was a full-on immersive and raw teaching and learning experience. Despite the intensity, the Zoom fatigue, the psychological stresses and the exhaustion, I wouldn’t have traded this class for anything.

Someday, hopefully soon, we will resume offering programs like the Semester in Dialogue in person, but I hope we don’t forget the core take-home lesson: like democracy, a course is at its best when it becomes a community, supporting each other in our vulnerabilities and speaking openly and honestly about what is happening in our world. We are at our best as teachers and students when we are open to listening, learning and growing together.