The crossed axes say it all. “Our university was quite literally hewed out of the woods,” says Scott Roberts, executive director of communications and marketing at Acadia University, founded in 1838 in Wolfville, Nova Scotia.

Over the phone, Mr. Roberts describes Acadia’s coat of arms. The original, granted by Windsor Castle’s College of Arms in 1974, is sitting on his desk in a royal red box, with the seal of Queen Elizabeth II and gold foil wrapping that normally encloses it when in storage in Acadia’s archives. The wolves’ heads are a whimsical nod to the university’s locale. The open books signify passion for learning. The Latin motto, In pulvere vincas – In dust you will conquer – is a fitting testament to the grit and all-out community effort of the institution’s pioneering founders. “Woodsmen chopped the lumber to build it. Women knitted mittens to [pay for] windows,” says Mr. Roberts. “It really was an institution built on hard work and perseverance.”

It has a deep history and set of values that any contemporary school of higher learning would be proud to claim as its foundation and embed in the symbols that adorn its degrees, stationery and legal documentation. It goes further than that: Acadia’s hockey and football teams are the Axemen and Axewomen; the university mascot carries an axe. Students know the origin of the symbol and are aware of its significance, in particular, to the founding notion of universal community inclusion.

“It represents the principles on which we were built and is quite relevant to who we are today,” says Mr. Roberts, pointing out that Acadia University was one of the first in the Commonwealth to enrol women (in the 1880s) and admitted its first African Nova Scotian in 1893.

But symbolism is not set in stone – or wood, in this case. As the university entered the 21st century, it decided that it made sense to shift the colours of the original coat of arms – blue, white and gold – to align with the university’s team colours of garnet and blue. In 2007, the new coat-of-arms image was registered in simplified form with the Canadian Heraldic Authority (founded in 1988, it now oversees all Canadian coats of arms). Besides the new colours, the Latin motto has been dropped. The updated image, with its continuing nods to the past, is now Acadia’s official logo.

Like Acadia, many Canadian universities – 60, in fact – are proud bearers of coats of arms. Older institutions like the University of Toronto and McGill University have used them as their chief brand image for decades. Variations on the arms’ imagery have been granted to about 40 colleges, faculties and other entitities within universities and, together, the coats of arms are key to school identity. Some universities, even those with coats of arms, may rely on a more modern logo as their chief institutional identifier, but that is frowned upon by lovers of tradition.

In his essay “Coats of Arms or Logos? Current Graphic Identity by Canadian Universities,” Jonathan Good writes about the ongoing differences between the two camps (his paper is based on the Beley Lecture he gave at the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada annual meeting in May 2014). Dr. Good, a Canadian and associate professor of history at Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia, writes:

“In the issue of Heraldry in Canada for June 1981, for instance, the editor railed against the replacement of [Université de] Montréal’s coat of arms with a logo, claiming that the latter resembled four conjoined toilet seats. On the design blog Brand New in 2009, the editor praised the University of Waterloo for considering a new dynamic logo to replace the coat of arms in everyday use, which he called ‘boring’ and ‘like thousands of other crests [sic].’”

Despite some views to the contrary by those who prefer logos, the design and use of coats of arms are surprisingly dynamic and flexible, as the Acadia example demonstrates. Updating colours, taking elements of an original coat of arms and letting go of others – this is all possible, though rules and protocols still apply. While Dr. Good says he can understand the viewpoint that coats of arms are “elitist and old-fashioned,” he doesn’t ascribe to this view, and he names some universities that have successfully used elements of their original imagery for a more simplified, modern identifier.

“I love to see heraldry in use,” says Dr. Good. “It keeps the medieval Western tradition alive. It’s classy, and there are ways of keeping it fresh. You just have to use it.”

McMaster University, for example, updated its coat of arms imagery in 1997, with a simplified shield design that gives a nod to heraldic tradition but is easier to reproduce in print and electronic form. “That’s a perfectly good way to go,” says Dr. Good. The original coat of arms, designed in 1930 when the university moved from Toronto to Hamilton, Ontario, incorporates fitting symbols, such as books and maple leaves, as well as a stag and oak tree that were the personal symbols of the university’s founder, Senator William McMaster. The university also uses a recognizable logo, and reserves the coat of arms for use by the chancellor and office of the president, on graduation diplomas and other significant university documents.

The original shield, with its motto, unusually in Greek (most mottos are in Latin), hangs prominently in University Hall and in the Council Room in Gilmour Hall: “Ta panta en Christoi synesteken,” it says – In Christ all things hold together. Why Greek instead of Latin? According to Gord Arbeau, McMaster’s director of public and community relations, the motto was intended to express the concept of a “Christian school of learning,” as stipulated in Senator McMaster’s will in 1887.

Université de Sherbrooke also went through a lengthy updating process with its 1957 coat of arms, first for its 50th anniversary in 2004, and again in 2007, this time involving the whole university community in brainstorming to create the final design. The latest coat of arms is so popular that some alumni are opting to pay a fee to have their diplomas reprinted with the new image. Sales of embroidered insignia have also increased, says Jocelyne Faucher, the university’s secretary general, vice- rector, international relations, and vice-rector, student life.

The coat of arms incorporates numerous symbols: the arms are four quarters, representing each of the Eastern Townships of Quebec; the cross and fleur-de-lis recognize the Catholic and French origins of the university’s founders. Also present is the floral emblem of the city of Sherbrooke. For the crest, a snowy owl is a symbol of wisdom, and for the supporters, foxes signify “intelligence, finesse, liveliness and speed,” according to Ms. Faucher. The Latin motto Veritatem in Charitate translates as “truth in love.”

“It reflects the intrinsic quality and virtue of the Université de Sherbrooke,” says Ms. Foucher. “It also refers to the university’s mission that focuses on open training, the promotion of critical learning and the quest for new knowledge through teaching, research, creativity and social commitment.”

How does a university go about obtaining, or updating, a coat of arms? It’s fitting that the Canadian Heraldic Authority, a branch of the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General, is itself situated in an impressively restored heritage building – the LaSalle Academy, circa 1847, on Ottawa’s Sussex Drive. On the wall of the entrance hall hangs a display of the coats of arms of the current and all past governors general. Each hand-painted shield is a mix of personal and ceremonial symbols – that of the current Governor General, David Johnston, includes tartan; Adrienne Clarkson’s, a Chinese phoenix rising and the colours red and gold.

Part head office, part artists’ workshop, this is where all Canadian applications for coats of arms are considered by Chief Herald Claire Boudreau and her team of heralds and designers. They help applicants through the process (for institutions such as universities, it can take one year) to select appropriate emblems for what will ultimately be a one-of-a-kind ceremonial object. By following age-old protocols and employing the knowledge and talent of heralds and artists, both individuals and institutions avoid anything tacky or inappropriate – the purview of ye olde heraldry “bucket shops” (ordering up a family coat of arms online, unless your family lives in an ancient palace, is likely to be an exercise in fakery).

But formality, argue the proponents of granted arms, is not tantamount to being hidebound. “If there’s a perception that it’s old-fashioned to have a coat of arms, we want to change that,” says deputy chief herald Bruce Patterson, who has worked for the Canadian Heraldic Authority since 2000.

A former high-school teacher with a passion for history going back to childhood, Mr. Patterson is one of five heralds – all positions are named after Canadian rivers, his being the Saguenay – who work to keep the tradition alive and well in Canada. As he points out, coats of arms have been around since the 12th century, when the knights of Europe began painting their shields to mark their allegiances as they went into battle. The French and English brought the tradition to the new world, and the protocols for granting and designing coats of arms have been under the auspices of the British crown for centuries. Those historical roots remain evident in the key components of today’s coats of arms, from the crest and supporters to the shield and motto. (For an inside look at how Universities Canada created its coat of arms, see “A coat of arms is born”).

But, says Mr. Patterson, today’s coats of arms reflect immense cultural diversity. For example, he has worked with a number of universities to design coats of arms that incorporate First Nations symbolism: Laurentian University included eagles in the Woodland Aboriginal art style, and the Emily Carr University of Art + Design used ravens on its crest and a Coast Salish spindle whorl.

“We work a lot in metaphor,” says Mr. Patterson, of the role played by the Canadian Heraldic Authority. The design and granting process, he says, “combine tradition with innovation.” Like Dr. Good, Mr. Patterson and his colleagues are not fans of corporate logos for universities, primarily because they see so much room for flexibility with a coat of arms.

“I think we just need to educate people about what’s possible. We have so many success stories among Canadian universities,” says Mr. Patterson. Adds Dr. Good: “A coat of arms can be timeless, relevant and forever new.”

A coat of arms is born: How Universities Canada found its armorial bearings

In 2002, Universities Canada (then the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada) created a poster that brought together the coats of arms of all Canadian universities that have one – a fitting way to celebrate the vibrant history of postsecondary institutions across the country. As they gathered together the images for the poster, the communications staff realized that it would make sense for the association representing Canada’s universities to have a coat of arms, too.

The creation process began in a dialogue between Christine Tausig Ford, now vice-president and chief operating officer at Universities Canada, and Bruce Patterson, Saguenay Herald at the Canadian Heraldic Authority. “I came at it as most Canadians would, with no understanding of what it all meant,” says Ms. Tausig Ford, referring to the complex process and protocols involved in designing a coat of arms. It took a year to settle on the symbols that would constitute the shield’s various elements, and to see the coat of arms completed to fittingly represented the organization’s mission, history and aspirations.

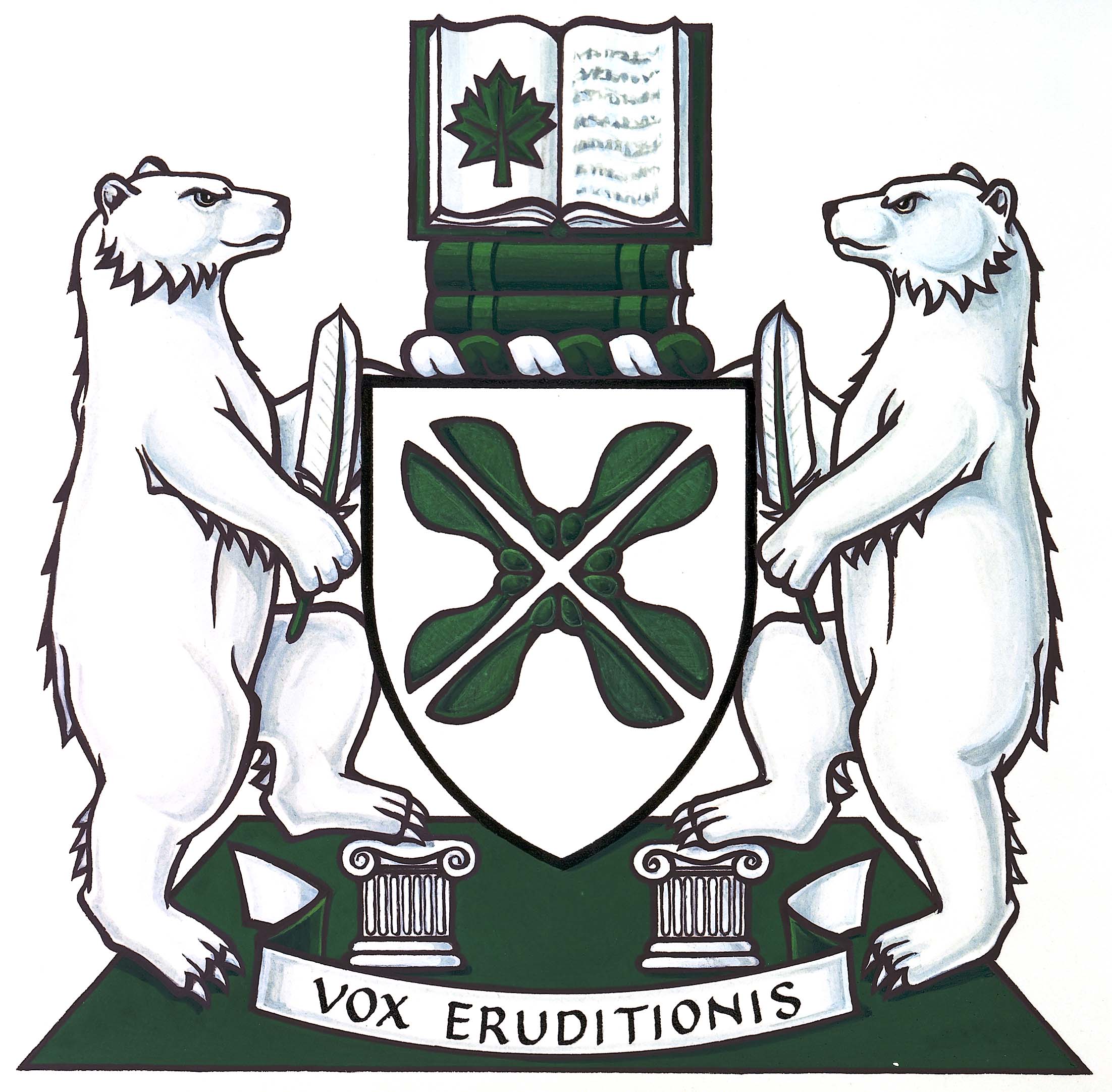

The colour green was chosen for its strong associations with tertiary education. Polar bears symbolize the idea of strength, and are appropriate for a coat of arms as “heraldic beasts of great antiquity,” says Mr. Patterson. “Bears are born formless lumps, and licked into shape by their mothers,” adds Ms. Tausig Ford. These bears hold eagle feathers, in recognition of support for aboriginal education. The maple keys in the crest’s centre are quintessentially Canadian and, like the bear metaphor, suggest the idea of nurturing the growth of the young. Open books suggest ideas and inquiry, the central notions of education. And the Latin motto, Vox Eruditionis, translates literally to “voice of higher learning.”

Today, the impressive shield hangs in the lobby of Universities Canada’s Ottawa offices, and is present for ceremonial occasions, both solemn and celebratory.

Freelance writer Mark Cardwell contributed to this article.