Canada has a long history of underperforming on measures of private-sector spending on research and development, and failing to capitalize on the commercial potential of scientific discoveries made in the country. And it has almost as long a history of coming up with government schemes intended to overcome those problems and turn Canada into an innovation nation.

One of the most recent of these schemes, announced in 2017, is the Innovation Superclusters Initiative. The idea was to replicate the success of well-known clusters around the world, such as California’s Silicon Valley, by encouraging closer collaboration between businesses, academic institutions and non-profits in specific areas, focused on industries in which Canada already had some competitive advantage. The initiative was to be given almost $1 billion, with the expectation that each cluster would at least match their funding with contributions from companies in their industry.

“It’s clear someone in the government was reading the literature about innovation, and the importance of density, and tried to imitate it,” says Alex Usher, president of Higher Education Strategy Associates, a consultancy based in Toronto.

But it quickly became apparent that political concerns would feature heavily in selecting the clusters. When the government announced that there would be five clusters, Mr. Usher says it signalled that the intention was to ensure each region in the country would get its own cluster, rather than selecting locations solely on merit. “It became a beauty contest for who was the best in each region, and every prospective cluster made sure they had members region-wide,” he says. “They essentially created five regional agencies to disburse money in a cool way.”

Read also: The curious story of the Global Innovation Clusters renewal

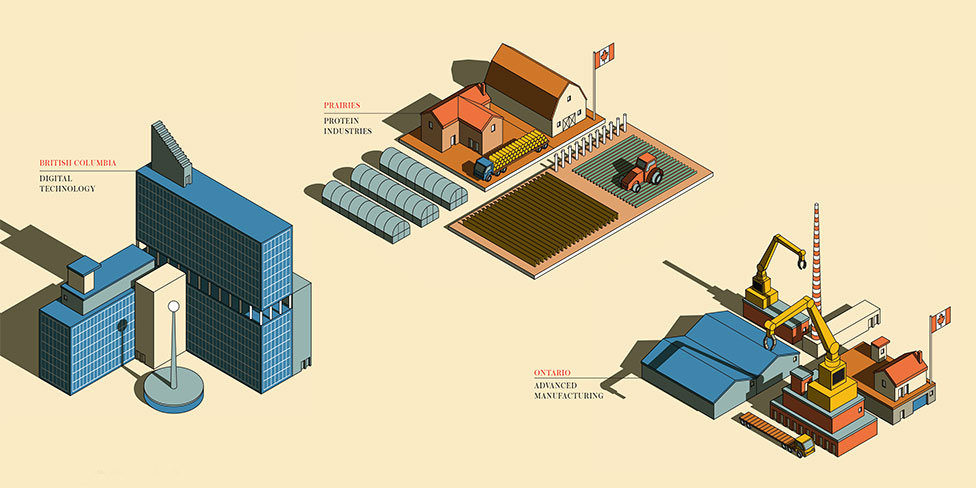

The five superclusters were announced in 2018. The Ocean Supercluster, based in Atlantic Canada, is focused on marine industries such as aquaculture, transportation, and oil and gas exploration. Scale AI, based in Quebec, is focused on using artificial intelligence to improve supply chains. NGen, based in Ontario, focuses on next-generation manufacturing. Protein Industries Canada, based in the Prairies, deals with plant-based protein alternatives. And the Digital Technology Supercluster, based in British Columbia, aims to bring new technologies such as augmented reality and cloud computing to sectors such as health care and natural resource development.

Even with the political interference, Mr. Usher concedes that the clusters are in general doing good work. “On the whole, despite the ridiculousness, the money is being spent pretty well,” he says.

But David Wolfe, co-director of the Innovation Policy Lab at the University of Toronto, is less charitable in his evaluation. “The project was very confused from the outset,” he says. “What the government wanted, and what they actually created were very different, and it was never clearly explained how and why it changed.”

With partners scattered across each region and even the entire country, the superclusters bear little resemblance to the highly place-specific or even technology-specific models they were ostensibly based on (such as the United Kingdom’s Catapult Network, a government research-and-development initiative). “It shows a lack of understanding of cluster dynamics, how they get seeded and how they grow,” says Dr. Wolfe. “You don’t build a cluster just by funding research.”

‘The jury is still out’

The federal government had high ambitions for the program, which they claimed would create 50,000 jobs and boost GDP by $50 billion within a decade. Now, four years into the experiment, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) says the clusters are “on track to meet or exceed program targets.” According to the department’s numbers, the clusters have approved more than 480 projects, worth over $2.16 billion, with 2,045-plus partners. These have already generated more than 850 new intellectual property rights for things such as patent applications and trademarks. At least $225 million of the total project value has been for 80 projects responding to COVID-19.

The clusters have also exceeded the government’s initial one-to-one target for matching industry funds – commercial and other partners have contributed $1.28 billion. And more than 7,100 organizations have joined, including many from academia, exceeding an initial target of 830 (although the level of engagement of each partner can vary widely).

Read also: We can no longer justify Canada’s ill-conceived superclusters

Beyond these high-level numbers, there isn’t a lot of public information about how the superclusters are doing, says Paul Dufour, a senior fellow at the Institute for Science, Society and Policy at the University of Ottawa. That makes it difficult to gauge how effective the program is. “I think the jury is still out in terms of the impact of the clusters,” he says.

There have been some independent attempts to evaluate the superclusters. A preliminary analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) found that things were moving slower than expected, based on data collected up to March 2020. By that point, the government had spent just $30 million on the superclusters, well below the $104 million it had originally anticipated. The PBO estimated that the 45 projects announced up to that point would lead to the creation of around 4,000 jobs, but it could not say whether those jobs were full-time, part-time, permanent or temporary.

The PBO report also found that, based on evidence from the literature on innovation, it was unlikely the government would realize its objective of increasing GDP by $50 billion – even the most optimistic scenario would be closer to $18 billion. And it found that ISED does not have a good way to measure the innovation improvements the clusters are expected to bring.

An analysis by John Knubley, a former ISED deputy minister who was deeply involved in creating the superclusters program, found the projects it supports are small on average – more like pilot programs – and the innovations that result are more incremental than transformative. But Mr. Knubley also noted that the superclusters had just started their work, and were only beginning to draw lessons about gaps in their ecosystems. As such, their success should be evaluated on a longer time horizon in keeping with the scale of their ambitions, he concluded.

Encouraging collaboration

Those directly involved in the superclusters, however, say they have already seen important successes. Jeff Larsen, assistant vice-president of innovation and entrepreneurship at Dalhousie University, says being part of the Ocean Supercluster provides his institution with support for research programs that help deliver real-world impact.

“It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement,” he says. “Large companies need access to the innovations from new startups and the talent that emerges from universities, while university researchers largely want to make an impact in the world. So it’s an opportunity to do that, to implement great ideas.”

Dalhousie, along with Memorial University of Newfoundland, is part of the Ocean Startup Project, funded by the Ocean Supercluster. It involves ocean-focused versions of the Creative Destruction Lab (CDL), a global network of innovation accelerators, and a university research commercialization program called Lab2Market.

In April of this year, Planetary Technologies, a Halifax-based company supported by CDL’s oceans stream that works closely with researchers at Dalhousie, won $1 million to continue its work toward the $100 million Musk Foundation Xprize carbon removal competition. The company purifies mine waste, producing hydrogen fuel and a mild bicarbonate solution, which it releases into the ocean. That can reduce ocean acidification and accelerate the ocean’s ability to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, allowing the company to sell carbon credits.

“Large companies need access to the innovations from new startups and the talent that emerges from universities, while university researchers largely want to make an impact in the world. So it’s an opportunity to do that, to implement great ideas.”

Such projects – involving multiple companies, university researchers and innovation accelerators – are a good example of how the superclusters can bring together different groups to help drive innovation, says Mr. Larsen. “The nature of so much research now is multi-institutional partnerships. It takes an ecosystem to solve big problems, it’s not individuals that solve them on their own,” he says. “Superclusters help bridge that and help us connect with external actors in a more efficient way through collaborative R&D projects.”

As the goal of the superclusters is not to advance research, but to commercialize it and create new products, it wasn’t initially obvious how universities and industry would collaborate in the program, says Julien Billot, CEO of the Scale AI supercluster. But in the case of artificial intelligence, the connection was easy.

“There are a lot of researchers in universities creating software that is absolutely ready to be implemented,” he says. “There is less of a gap between research and operations.”

Universities have a fundamental role in both the creation and the activities of the superclusters, Mr. Billot says. Part of the decision to focus Scale AI on applying artificial intelligence to supply chains was that there were already several top-notch academic researchers focused on supply-chain issues in Montreal, he says. Around 83 per cent of the cluster’s projects include university partners. “When industry comes to us with projects, we really look at the science behind it and encourage them to partner with universities to ensure that the science is at the right level,” he says.

Shaping the next generation

Alain Francq, director of innovation and technology at the Conference Board of Canada, has worked on several projects supported by the NGen supercluster on both the university and company side. He says collaboration between universities and companies is at the heart of the superclusters, with researchers bringing new ideas, and companies figuring out how to implement them.

“True innovation happens at the interface of traditional disciplines,” he says. “You need to bring together groups that are different but complementary to create a consortium that would not have come together without the supercluster funding.”

As educational institutions, universities and colleges are also an important source of the people and skills that companies need in order to innovate, expand and compete in the marketplace. “A big part of the superclusters is the long game on talent,” says Mr. Francq. “They almost always partner with a postsecondary institution to help create the next generation of highly qualified personnel, and inform the postsecondary system what future skills are needed.”

Scale AI, for example, is funding workforce training programs, customized for its company partners’ needs, at more than 40 universities, colleges and CEGEPs, says Mr. Billot. The aim is to help train the people who will be needed to implement the innovations developed by the superclusters.

“True innovation happens at the interface of traditional disciplines. You need to bring together groups that are different but complementary to create a consortium that would not have come together without the supercluster funding.”

As the PBO report shows, many of the superclusters got off to a slow start. Mr. Billot says this was definitely the case in his experience. “AI is not a mass-market technology yet. We had to educate people and companies on why they should use it,” he says. “That’s a time-consuming and slow process.”

The chaos unleashed by COVID-19 didn’t help, he adds, but things started to pick up in 2021 and 2022, as companies seek new ways to strengthen supply chains disrupted by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

And the government is continuing to support the superclusters program. The 2022 federal budget included another $750 million to keep them going for another five years, money that will be distributed among the five clusters on a competitive basis – though that is reportedly just half of what ISED reportedly asked for. (The budget also renamed the program “Global Innovation Clusters,” but that change does not seem to be catching on among those involved.)

That kind of long-term support is critical to allow the superclusters to achieve the goals set for them by government, says Mr. Dufour. “We can’t expect immediate results from an experiment like this,” he says. “So sustainable funding is important – we can’t turn the tap on and off.”

Those involved in the clusters agree that the kinds of changes they aim to bring to Canada’s innovation landscape won’t be realized after just four or five years. “We tend to look only at the near term,” says Mr. Francq. “But when we’re talking about big systems and intractable problems, those require long-term views.”

Canada took a major step by investing in superclusters to encourage collaboration between academia and the private sector to speed up the knowledge/technology transfer for societal use and also for better education and training of next generation of talent.

Protein Industries Canada, for example, is in an ecosystem developed through more than a century through research, innovation and education in agricultural sciences at the University of Saskatchewan and fills an important role to further hasten the collaboration between the academy and the industry. This ecosystem also incldues Global Institute of Food Security created through a partnership between Government of Saskatchewan, Nutrien and the University of Saskatchewan. The collaboration among entities such as USask, PIC and GIFS is actually critically to provide the technologies urgently needed by producers and food processors.

Most of the evidence till now and the early indicators of what lies ahead point to the success of superclusters. Therefore, it is great that Canada decided to provide funding for the superclusters in the recent budget.