When news of a mosquito-borne virus that might be causing birth defects in Latin America started to make headlines earlier this year, Brock University professor Fiona Hunter was more than ready to take a closer look at the problem. Brock recently built a Containment Level 3 laboratory for Dr. Hunter’s research, making hers one of Canada’s most advanced and secure insectaries, where mosquito populations carrying health threats can be isolated and studied. For the last 15 years, Dr. Hunter’s lab has focused on the notorious West Nile virus and the advent of Zika was a welcome change.

“This came at the perfect time,” she said. “I have a lab full of grad students who are finishing up their work on West Nile and they can easily move over into doing Zika work. They’re excited; I’m excited.”

Some of those students have more than a purely scientific interest in the outcome. Two members of Dr. Hunter’s lab are participants in Brazil’s Science Without Borders program, which augments the education of students by sending them to other countries for a year. The pair in Dr. Hunter’s lab come from Brazil’s northeast, which is a Zika hot zone.

“One of them actually had Zika before she came to Canada,” Dr. Hunter said. “They are really invested in doing this work.”

The tropical mosquito that primarily transmits Zika goes by the formal name Aedes aegypti. While the species cannot survive in Canada, Dr. Hunter notes that it is not necessarily the only one that could carry the virus. She is therefore interested in whether domestic mosquitoes could also be carriers — which could put the disease in an entirely new context for Canadians, who now remain unlikely to encounter Zika unless they travel to an affected country.

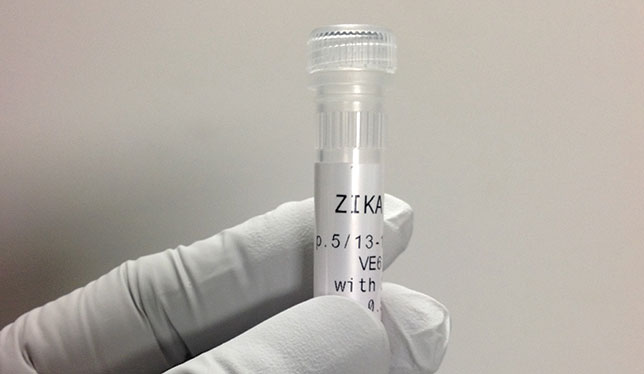

By early February, when the World Health Organization declared the spread of Zika in South and Central America to be a global public health emergency, Dr. Hunter had already contacted the Public Health Agency of Canada to obtain samples of the virus for testing. She began by working on older strains collected several years ago, but PHAC will be providing her with newer samples taken from tourists recently returned to Canada after becoming infected with the virus.

In March, Dr. Hunter travelled to Brazil for a summit where a critical mass of expertise on Aedes aegypti had assembled to develop strategies for dealing with the spread of Zika. Part of the challenge is determining just what caused this dramatic spread to happen.

According to Philippe Lagacé-Wiens, an assistant professor in the University of Manitoba’s department of medical microbiology, the answer partially lies in having the right bug show up in the right place. He points out that Zika is far from new. The disease was first identified in the 1940s and surfaces regularly in different parts of the world, including a major outbreak in French Polynesia in 2014.

“This is a virus that’s made its way around the world in a fairly predictable fashion, if we followed the path of related viruses that are transmitted by the same vector,” he said. Dr. Lagacé-Wiens, who also works at a Winnipeg tropical medicine clinic, compares Zika’s global trajectory with that of chikungunya, another virus carried by the same mosquito and which appears in different population clusters every few years.

Dr. Lagacé-Wiens notes that what sets this current appearance of Zika apart from previous outbreaks is that both the virus and Aedes aegypti are flourishing on a crowded continent rather than contained to small South Pacific islands. “It’s a very large population, all of whom were susceptible to the virus when it showed up,” he said. “What created this mass epidemic of Zika is a perfect storm.”

Compared to potentially lethal ailments such as dengue, salmonella or malaria, Zika is comparatively innocuous: upward of 80 percent of infected people have no symptoms while most others experience aches and pains no worse than a cold. The most troubling aspect of the disease is its possible effect on pregnant women, whose children may be born with underdeveloped or undeveloped brains (a condition known as microcephaly).

“We are investigating how Zika virus infection affects different cell types, which could provide clues as to how the virus causes damage in utero,” said Thomas Hobman, Canada Research Chair in RNA Viruses and Host Interactions at the University of Alberta. He is leading an interdisciplinary group that is exploring the virus’s biomolecular mechanics, which could also make it possible to retrofit hand-held blood sugar measurement devices for an on-the-spot diagnosis of Zika.

Such an innovation could significantly improve the ability of medical authorities to keep pace with the outbreak, since existing tests call for the full resources of a hospital.

Happy to here working on fight against Zika Virus.

I pray God will give you strength and wisdom to be helpful to the world