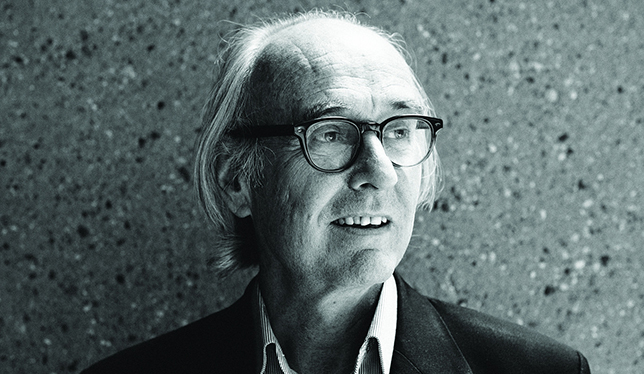

Donald MacPherson is no stranger to controversy. A leading figure of drug policy reform in Vancouver – whose downtown eastside has been referred to as “ground-zero” for the opioid crisis in Canada – he is the director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, which is housed in Simon Fraser University’s faculty of health sciences. Mr. MacPherson is known for bringing the Four Pillars Approach to Vancouver at the height of the 1990s HIV and drug overdose epidemics. He also co-authored the book, Raise Shit!: Social Action Saving Lives. Tonight, he will deliver a lecture as the recipient of the 2017 Nora and Ted Sterling Prize in Support of Controversy at SFU, where he is also an adjunct professor. We recently spoke with Mr. MacPherson to get a sense of what he’s about.

University Affairs: First off, congratulations. What were your thoughts when you found out you were receiving a prize “in support of controversy”?

Donald MacPherson: Thank you. I was very surprised. I didn’t even know I was nominated. Some staff and another professor at the university did it without telling me, so it was quite funny. I have a high regard for this prize. One of my drug policy heroes, Bruce Alexander, received it about 10 years ago and he’s a real powerhouse in the field; he’s retired now. That was the last Sterling Lecture I was at and it’s always a great time.

UA: I guess you’ll be the one delivering the lecture this year. What do you plan to speak about?

Mr. MacPherson: Yes, that’s part of the deal. They have a ceremony and they say good things about you and then you do something for 40 minutes and explain what you’re on about. I think I will be speaking about the absolute, catastrophic failure of our current drug policies to protect the health, well-being and security of Canadians. The drug laws are so out of date. They’re based on an ethos of racism, of discrimination, of social control. They’re not about a rational discussion about the harms and benefits of drugs.

UA: I’ve read that in the 1990s, you were integral in spearheading change in Vancouver’s municipal drug policy with a strategy that was considered very radical at the time. What went into creating that strategy and how did you get city council and other levels of government to actually pay attention to it?

Mr. MacPherson: What was important about the Four Pillars project was that it was a local, municipal strategy. So it responded to a local, public policy disaster: an HIV epidemic among injection drug users and an overdose epidemic in the ’90s in the middle of our city. So it was very important for the city to take some leadership in figuring out some solutions. If you look at the history of the evolution of drug policy in Europe, municipalities played a strong role in identifying potential ways of moving forward that would benefit all citizens, including those citizens who used drugs. We really borrowed the Swiss model of the “four pillars” of harm reduction, drug treatment, prevention and enforcement because it had such a profound impact in Europe.

UA: At the time, were needle exchanges and supervised injection sites a shock to Canadians?

Mr. MacPherson: Needle exchanges were in existence and we had a very large one here in Vancouver. It was actually under a lot of pressure because a lot of people were against harm reduction in general. They saw it as not solving a problem because it was not about stopping people from using drugs. Harm reduction came to the fore after the HIV situation developed. From a public health perspective, the most important prerogative is to prevent the transmission of HIV – it’s a much more serious thing than an addiction. That goal trumps the issue of abstinence.

UA: Recently, Vancouver has experienced another wave of drug overdoses with the opioid crisis. Do you see links between what you saw in the ’90s and what we’re witnessing now?

Mr. MacPherson: It’s very similar, only worse. A couple of things come to mind. First of all, we didn’t scale up the Four Pillars program. We spent a tremendous amount of energy just to get the first injection site in the ground, which was full the first day it opened. We needed to do what the European cities did – Zurich has five consumption rooms in their city, Amsterdam probably has 15 or 20. You have to scale up the interventions to meet the scale of the issue you’re dealing with, and that’s what we didn’t do.

It became very political again when the Harper government came into power and they were very anti harm-reduction. Things slowed down again, and that’s sad because it meant we were not well-prepared on the ground for this next round, which was again a supply problem. In the 1990s, something happened in the illegal drug market where suddenly, heroin became very pure. People were using heroin at doses they weren’t prepared for. This time it was fentanyl, which is stronger than heroin, and people were using it at unknown doses. Both situations were caused by a toxic drug market. So, it’s a total failure of our system and it’s so bad that we need to think of new harm reduction interventions and the one we think will make the biggest impact is to actually supply drugs to people: replace the market. Here we have a community of people who use drugs; their source is poisoned and we’re doing nothing to replace that source.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.