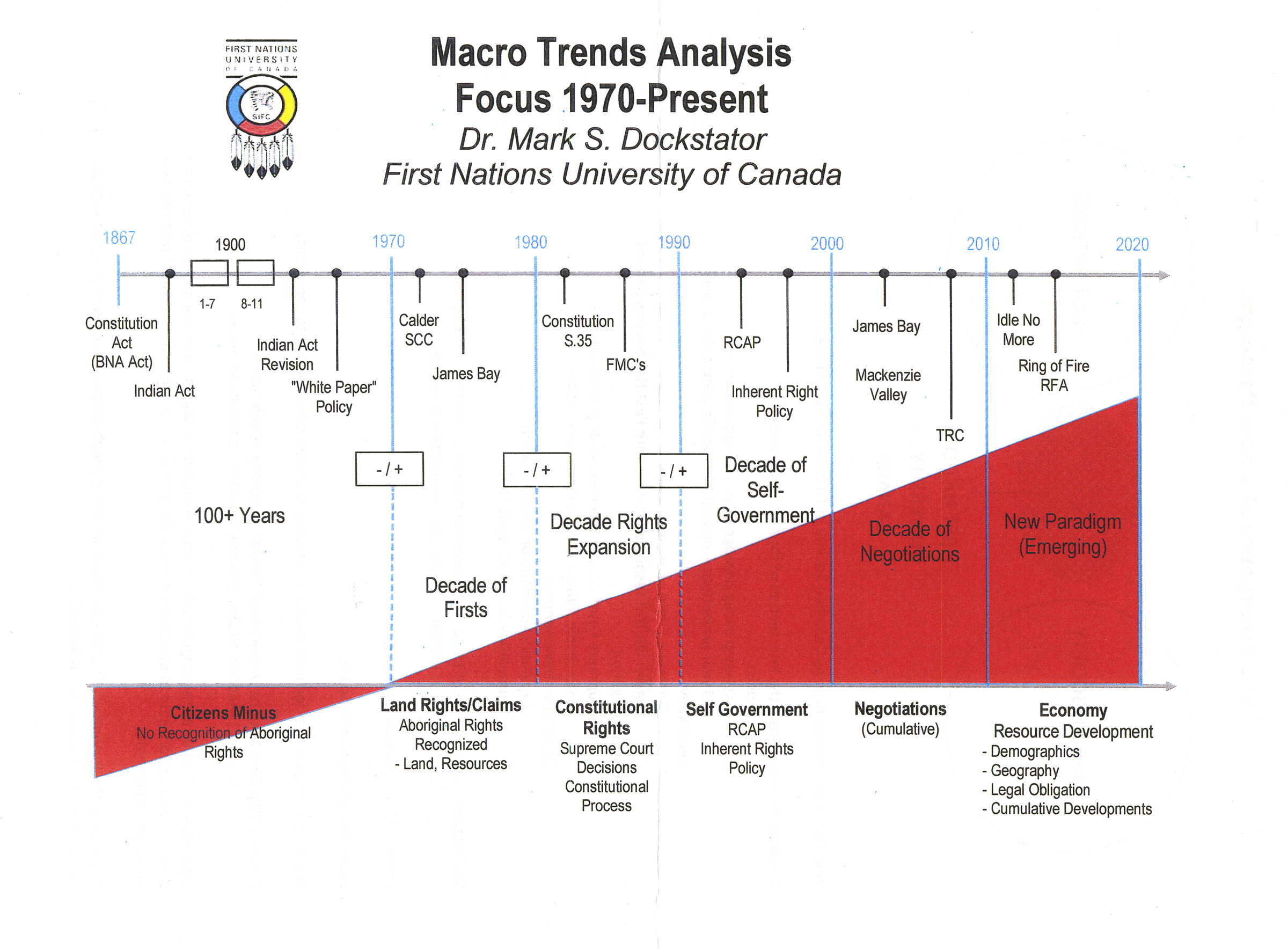

Mark Dockstator, president of First Nations University of Canada, uses a chart to illustrate how the relationship between First Nations people and Canadian society has evolved over the years. It shows aboriginal people moving from a state he calls “citizens minus” prior to 1970 to being a group that by 2015 had made significant strides in attaining land claims agreements, constitutional rights, self-governance and, most recently, in reasserting Native title over natural resources on traditional lands.

“Over the last 40 years we’ve seen some incredible developments occur,” says Dr. Dockstator. “But it’s only recently that that change has come to the attention of the larger Canadian society.” The reason for this, he explains, is that aboriginal issues are now having a direct impact on the country’s economy and on Canadians.

The fortunes of the institution Dr. Dockstator leads in some ways mirror those of First Nations people. What started as a modest experiment to provide aboriginal youth with “a bicultural, bilingual education” has evolved into Canada’s only aboriginal, university-level institution. “We are not just a Native studies department or a mainstream university with a focus on indigenous learning,” proclaims its strategic plan. “We are a completely indigenous institution.”

Neither journey has been a smooth one. But as FNUC prepares to celebrate its 40th anniversary in 2016, its outlook seems brighter than it has been in years. Enrolment is on the rise, the budget is balanced and, under Dr. Dockstator’s leadership, the institution is poised to take on a new expanded role. He says, “We see ourselves situated in the middle of that emerging paradigm” between First Nations and Canadian society.

Dr. Dockstator, 57, was appointed president of FNUC in July 2014. He previously taught at Trent University and was the first aboriginal student to graduate with a PhD in law from York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School.

The role he foresees for FNUC is “to play a broker, a mediator; to build bridges; and to act as a meeting space [for] these two emerging elements.” This could include mediating for companies that wish to negotiate mining, logging or other resource agreements with First Nations groups. FNUC could provide logistical support and academic research to help the two parties forge partnerships, he explains.

Also high on the president’s agenda is boosting course enrolment from its current level of about 5,500 part-time and full-time students. In the lead-up to its anniversary, FNUC launched a recruitment campaign with a tagline that asks: What’s your Soul Reason? “It’s a very competitive market out there,” observes Dr. Dockstator, and many universities and colleges are looking to attract aboriginal youth. “We want to maintain our competitive edge.”

The institution is experimenting with new types of course offerings, as well. It has been developing and test marketing a new non-credit executive training course it hopes to introduce this summer aimed at non-aboriginal business leaders who want to work more closely with indigenous groups.

From its early days, FNUC has held a unique place in Canada’s postsecondary system. It was founded in 1976 by the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations as a federated college of the University of Regina. At the time known as the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College, the fledgling institution opened in the fall of that year with just nine students. The college thrived, and in 2003 it moved to its current home, a building designed by renowned First Nations architect Douglas Cardinal. It changed its name to First Nations University of Canada.

“The college was really seen as a bold experiment,” says Blair Stonechild, a professor of indigenous studies, who has been teaching at FNUC since its inception. First Nations elders wanted to offer students an education that would combine the best of indigenous culture and Canadian culture, and an education that would be controlled by aboriginal people. “We were choosing how to do it,” he says.

“Right from the get-go it had a huge impact,” adds Don McCaskill, professor of indigenous studies at Trent University. “There was a lot of excitement that this was different from other [indigenous studies] departments.” The creation of the institution likely resulted in a greater number of aboriginal students pursuing a postsecondary education than might have been the case otherwise, he adds.

His sentiments are echoed by Sonia Prevost-Derbecker, vice-president of education at Indspire, an indigenous-led charity group that supports aboriginal education. “In its design and from its inception, it has proven to be very helpful in supporting our community to envision themselves at a place of higher education,” she says. The fact that most faculty members are aboriginal creates a welcoming environment for First Nations youth. “It means greater access at the end of the day,” says Ms. Prevost-Derbecker.

But the institution also faced major hurdles over the years, including allegations of political involvement by the Saskatchewan chiefs and allegations of financial mismanagement, criminal investigations, and numerous dismissals and resignations of faculty and staff. Universities Canada (formerly the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada) placed the institution on probation for a time pending significant governance reforms.

Tensions reached a boiling point in 2009 when the federal and Saskatchewan governments withheld funding. The school seemed destined for closure. But an agreement was struck that saw administrative and financial control of FNUC handed over to the University of Regina. Government funding was ultimately restored.

“It was something that was unquestionably disappointing and difficult,” Dr. Stonechild recalls, but he remains sanguine about the ordeal. “It was almost a type of learning phase that First Nations, especially the leadership, had to go through,” he says. FNUC has now entered its “adult phase,” he adds. “I think we’ve found our legs, so to speak.”

FNUC’s board is now comprised of First Nations educators and other professionals rather than political appointees. Its budget has been balanced in each of the past four fiscal years. Full-time enrolment was 754 in the 2014 academic year, largely unchanged from 2013 but up 33 percent from 569 in 2011. (An additional 4,700 students, mainly from U of Regina, take courses at FNUC.) It has some distance to go before returning to levels of 1,000 full-time students or more that were typical before the troubles began, but the trend is still a welcome one.

“I think the increasing enrolments are reflective of a successful turnaround,” says Dr. Dockstator. “The confidence in the institution has returned.”

Rebuilding FNUC’s reputation will be “a monumental task,” but there’s no reason it can’t be done, adds Trent’s Dr. McCaskill, who is a friend of Dr. Dockstator’s and a former colleague. “The changes that have been made previous to his arrival and the changes he will make will hopefully result in the university turning its fortunes around.”

First Nations University has a worthy proponent and sharp mind in Dockstator.