When Chanda Prescod-Weinstein lived in Toronto during graduate school, she resided in the building next to where, 11 years later, Regis Korchinski-Paquet fell 24 stories to her death from the balcony of her family’s apartment after police were called in for assistance. Since her death on May 27, the 29-year-old has become a household name, like Black Americans George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, as Black Lives Matter protests sweep through the United States and Canada.

“That High Park apartment is where I also once had a traumatizing interaction with what I will politely describe as two extremely cruel Toronto police officers who were the only respondents sent to what was ostensibly a medical emergency,” Dr. Prescod-Weinstein, now an assistant professor in physics at the University of New Hampshire, explains. “Regis could have been me 11 years ago.”

Dr. Prescod-Weinstein’s wrote about her proximity to Ms. Korchinski-Paquet and her experience as a Black woman in science for the Particles for Justice website. Both she and the group played an integral role in a wave of protests against anti-Black racism in science that took place primarily online last month.

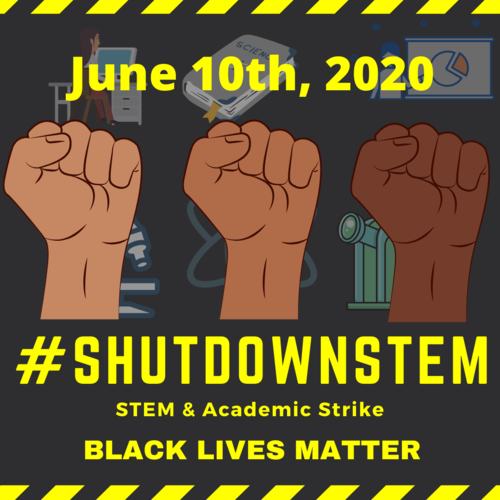

Particles for Justice is a collective of physicists that was created in 2018 in response to sexism in the field. After witnessing the recent deaths of Black and Indigenous people in both the U.S. and Canada, and seeing peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters harmed by police – all amid a global pandemic – the members of Particles for Justice felt compelled to act. The group penned a powerful call to action in early June, collected almost 6,000 signatures of support in a pledge to protest and, working with the organizers of the #ShutDownSTEM protests, called on their colleagues across academia and around the world to join them in a Strike for Black Lives on June 10.

“The movement for Black lives isn’t a hobby,” Dr. Prescod-Weinstein continues. “It’s a movement to save my life, my mom’s life, my cousins’ lives, the lives of beloved friends and chosen kin, and the lives of all Black people, including all Black scientists and Black science students.”

For the June 10 protests, Strike for Black Lives and #ShutDownSTEM organizers encouraged supporters – with the exception of the research community working to end the COVID-19 pandemic – to stop all usual academic work for the day and either cancel classes and research groups or replace them with discussions about anti-Black racism. The day was meant for non-Black academics to educate themselves and create plans of action to carry this work forward. It was also intended as a day for Black academics to prioritize their needs by either resting, reflecting or taking action alongside colleagues.

The Particles for Justice website points out that the Strike for Black Lives was not about book clubs, diversity and inclusion talks or training about implicit bias. “We are calling for every member of the community to commit to taking actions that will change the material circumstances of how Black lives are lived,” the call to action reads. And many members of the academic community in Canada did participate – including the department of physics and astronomy at the University of British Columbia, McGill University’s faculty of medicine, researchers at Mila and SNOLAB, the Canadian Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the Canadian Association of Physicists, to name a few.

Statement from the CSVP executive in support of #BlackLivesMatter #ShutDownSTEM #BlackInSTEM #BlackintheIvory #ShutDownAcademia, with some of the steps we’ll be taking to promote and increase diversity and inclusivity within our community https://t.co/x2DWYb3Mr1

— Thomas Cullen (@cullen_thomas) June 10, 2020

Djuna Croon, a postdoctoral research associate at TRIUMF and a Particles for Justice member, says she didn’t know what kind of participation to expect in the protest. “We wanted people to actually take the day and strike, and not work on normal academic activities or other sort of mentorship or teaching,” she says. “That’s kind of a big ask, and it was also not something far into the future that you can plan around. So I was positively surprised.”

In the U.S., several journals and publications suspended normal operations. The American Association for the Advancement of Science, which publishes the magazine Science, made its articles about race and diversity in science available for free without registration or subscription. The e-print server arXiv, which Dr. Croon says is used daily by those working in the world of physics also paused regular business and instead encouraged its audience to use the time they’d normally spend on reading its daily announcement or submitting an article to learn about and discuss racism.

Brian Shuve, who’s Canadian and a professor in the department of physics at Harvey Mudd College in California, says he’s witnessed racism during his time in academia and that it’s “insidious” in physics. “The whole culture of this field is very oriented towards kind of idolizing our superstars, that there are a few brilliant people who are leading the way. And coincidentally, the vast majority of those people are white men,” he says.

Dr. Shuve is also part of Particles for Justice and says Black scientists, including Dr. Prescod-Weinstein and Brian Nord, an astrophysicist and researcher at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in the U.S., provided vital guidance in organizing the strike. He says the group was motivated not just by Black Lives Matter protests, but by the “insufficient response” to racism by their institutions.

“We’re starting to see some pushback against the sort of notions of equity, diversity and inclusion, the way that they’ve been kind of turned into a slogan by a lot of institutions,” he adds, noting that he’s heard from Black colleagues that they feel they’re not yet well served by such initiatives.

Tim Bardouille was one of the many non-Black academics, like Dr. Croon and Dr. Shuve, to support Black colleagues by participating in the strike (Dr. Bardouille is multiracial). According to Dr. Bardouille, an associate professor in Dalhousie University’s department of physics and atmospheric science, there’s been a transparent process at his university for addressing inequity and racism in higher education. Among a few reports the institution has released on discrimination, it recently took a hard look at itself in a report about Lord Dalhousie and his history with slavery, he says.

Motivated by Black Lives Matter protests, the Strike for Black Lives and #ShutDownSTEM, Dr. Bardouille organized a Black Lives Matter march in Halifax on June 10. About 300-500 people attended, many wearing masks and following proper social distancing guidelines. The turnout speaks to how much people felt like they needed an outlet, Dr. Bardouille suggests. “They needed to be able to speak truth to power and get out there and feel like they were at least acknowledging their awareness, if not taking some small action.”

He says the Halifax protest was not a Dalhousie sponsored event, but that the university was in support of it occurring. And he’s optimistic the momentum from the day of protest will push the university to continue to push itself. “Some of those [report recommendations] have been acted upon and some haven’t,” he adds “I’m hopeful that the awareness that’s happening right now. … will be motivation to get more of those recommendations in place.”