Memorial University has adopted a new policy that will significantly change how research involving Indigenous people is conducted. The Policy on Research Impacting Indigenous Groups sets out to make scholarship involving Indigenous groups, cultures or lands more inclusive, responsive and reciprocal than previously required, and encourages relationship-building at every step of the research process.

Max Liboiron identified the need for a standalone policy tailored to the university’s research environment early in her two-year appointment as associate vice-president, Indigenous research (her appointment ended this August). “I decided that we needed something very concrete,” Dr. Liboiron says. “Not awareness, not workshops, not bias training, but something that actually had accountability built in, because accountability was where we were really suffering.”

The new policy frames how researchers can and should hold themselves accountable to the Indigenous communities they work with through agreements in principle, a formal Indigenous research review and measures to obtain ongoing participant consent. But it also holds the university accountable to its researchers – the institution has a duty to offer resources and support to help researchers meet the new expectations set out in the policy, Dr. Liboiron explains. It mentions, for example, that researchers may seek guidance from Memorial’s Indigenous Research Advisory Group, experts versed in “ethical and impactful Indigenous research.”

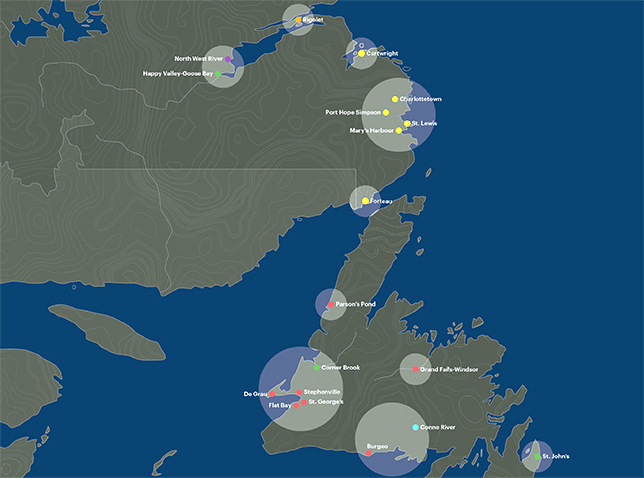

[Click the image to see a larger version of the map]

The policy was drafted by an Indigenous-led working group that represented three separate parts of the province. It consisted of Dr. Liboiron, who is Métis and based in St. John’s; Kelly Anne Butler, who is Mi’kmaw and a student affairs-Indigenous affairs officer at Memorial’s Grenfell campus in Corner Brook; and Michele Wood, an Inuk researcher in Labrador. Their process was informed by an expansive engagement process that Dr. Liboiron says included “Indigenous rightsholders, university stakeholders, faculty, students, experts around the world in Indigenous research, other ethics review boards.” Dr. Liboiron also consulted with Catharyn Andersen, special advisor to the president on Indigenous affairs, who had been collecting feedback through a separate informal engagement campaign in nearly a hundred communities around Newfoundland and Labrador with significant Indigenous populations.

“Altogether, we consulted about 2,000 people on the policy,” Dr. Liboiron says. “At Memorial, the average is less than 50 [people consulted] for a policy. This was unprecedented.”

While the scope of consultation is impressive, Dr. Liboiron says she worries it could create a double standard. “Now there’s the potential for an expectation that Indigenous or diversity policies actually have to exceed a norm to be valid,” she says. “It’s really hard to consult 2,000 people, especially in this province. It took two years and a full-time position to do it. That can’t become [the norm] if it means that certain Indigenous things will never pass.”

The policy is one of several new initiatives that Memorial has recently undertaken as part of its efforts to improve relationships with Indigenous people. A new Indigenization strategy is in the works, and this summer, the university approved the School of Arctic and Sub-Arctic Studies, its first academic unit based in Labrador which will feature an academic council with voting seats reserved for local Indigenous groups.