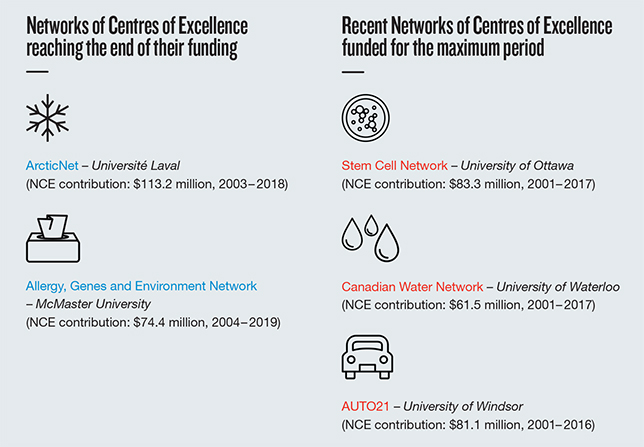

A quietly made funding change could affect the fates of several multimillion-dollar Canadian research networks. Though there was no major announcement, the details of the latest Networks of Centres of Excellence competition, posted online in August, reveal that research networks that have already received the maximum 15 years of funding may again apply for funding as “established NCEs.” That means several NCEs, including ArcticNet, AllerGen and the Stem Cell Network, might not have to wind down their activities as anticipated.

In this latest competition, $75 million in federal research money is up for grabs and networks can apply for as much or as little funding as they deem necessary. Any NCE that will complete, or has completed, its final funding cycle by March 31, 2019, is now eligible to apply for an additional five years of funding. However, a minimum of 40 percent of funds will go to new NCEs. The deadline for letters of intent is November 15.

“We’re hugely encouraged by this move because, up until this point, the lack of renewal opportunity was really hampering some of our strategic initiatives,” said Leah Braithwaite, the executive director of ArcticNet. The network was created in 2003 to study the impacts of climate change in the coastal Canadian Arctic; its funding was scheduled to end in 2018. Funding for AllerGen, a network focused on allergic diseases, runs out in 2019.

The Stem Cell Network, meanwhile, saw its NCE funding end this year; but, the network received separate funding of $12 million and $6 million respectively in the 2016 and 2017 federal budgets to continue its clinical research, so its future was less in doubt.

The NCE program is jointly administered by the three federal granting councils: the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Networks created under the NCE program were originally awarded funding for a maximum of two seven-year terms, which was later changed to three five-year terms.

The time frame was seen by the program’s administrators as appropriate to accomplish an NCE’s goals, whether that was solving a medical treatment challenge, bringing new products to market, or conducting the kind of research and development that would attract sustainable industry funding. But NCE leaders felt the hard limit cut short the potential of these networks and most shut down after their funding ended.

Lucy Lai, a media and public affairs officer at NSERC, said in a written reply that the change was made in response to frequent calls from the research community to remove the limits. “It was also referenced in the Fundamental Science Review,” she noted, referring to the 2017 report of Canada’s Fundamental Science Review panel, also known as the Naylor report.

Researchers at established NCEs are hopeful that the renewal option will continue in future competitions, but that remains up in the air. “We cannot predict what rules will be in place for future competitions,” said Ms. Lai.

Ms. Braithwaite said that, given the accelerating pace of climate change, ArcticNet’s continued work will be vital to informing environmental policy. With scientists and stakeholders from dozens of universities, government agencies, Indigenous research organizations and industries, ArcticNet’s research runs the gamut from investigating how climate change is affecting marine ecosystems to determining what melting permafrost means for housing, transportation and industrial infrastructure. Renewed funding will also allow the network to take advantage of the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, she said, which is scheduled to open in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, this fall.

NCEs that have already disbanded are also able to apply again. But Peter Frise, who headed the AUTO21 NCE, said he won’t be attempting to rebuild the network. “A huge amount of effort is expended to get these organizations up and operating and building all the connections,” said Dr. Frise, a professor of engineering at the University of Windsor, where the automotive research network was based. The NCE shut down in 2015 after receiving a total of $81 million in NCE funding over 14 years. According to the NCE website, AUTO21 “saved lives, reduced greenhouse gases, increased fuel efficiency and advanced the competitiveness of the Canadian automotive sector.”

At the time AUTO21 was shutting down, Dr. Frise told the CBC: “I think [these] organizations should exist as long as their purpose is viable and there’s a need for them, and they’re being used and taken up by the community. To choose in advance a certain number of years of life for them and shut them down … I’m not sure what the rationale would be for that.”

Bernadette Conant, CEO of the Canadian Water Network, said her network also won’t be applying for renewed funding in the current competition. CWN received $62 million from the NCE program from 2001 until earlier this year. Reapplying for funding would require the network to “try too hard to shape ourselves back into what we have evolved from,” Ms. Conant said.

Researchers at CWN aren’t pursuing new projects, she explained, but rather are looking at how they can scale up existing pilot studies and do more knowledge translation. Ms. Conant said she thinks the NCE competition favours those proposing new studies. However, she said her network is looking at ways to go “to the next phase.” A separate NCE program does fund networks dedicated to knowledge mobilization.

Even for an established NCE, continued funding is not guaranteed. Some NCEs weren’t renewed beyond one term, including the vaccine development-focused CANVAC, which received funding for a single seven-year term that ended in 2007.

In general, the lack of long-term public funding for innovation-focused research has made it difficult for Canada to compete on the world stage, said Dr. Frise. “It has made Canada an unreliable partner in innovation.” Not to mention, “the starting and stopping of funding is simply wasteful,” he said.