After noticing a decline in interest and engagement among her students in previous years, Pamela Walker, a history professor at Carleton University, has had major success with a different kind of classroom resource: role-playing games.

Reacting to the Past (RTTP) is a series of games that combines role-playing and educational pedagogy. Developed during the 1990s by Mark C. Carnes, a history professor at Barnard College in New York, RTTP games are set during historical events with students assigned the roles of historical figures.

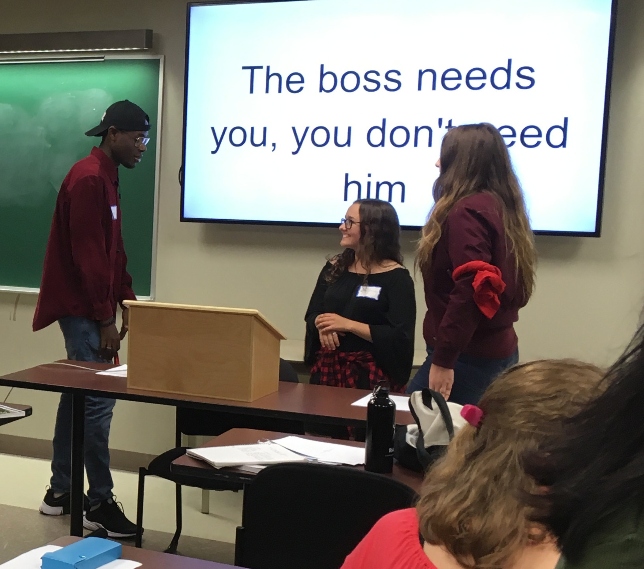

Students must conduct extensive research on their characters before playing out the game’s scenario. They are graded based on a rubric that considers the intellectual content of the game, which requires writing papers that engage with relevant historical texts and presenting speeches from their character’s perspective that demonstrate an in-depth understanding of the historical context and issues. These games aim to teach invaluable skills such as historical research, public speaking, debating and conflict resolution.

Dr. Walker was introduced to RTTP games through her colleague Gretchen Galbraith, the dean of the school of arts and sciences at SUNY Potsdam and vice-chair of the board at the Reacting Consortium, the academic association responsible for developing and publishing the RTTP series. While initially skeptical, Dr. Walker attended an RTTP conference where she underwent training on how to run the games in class. After this, she decided to use RTTP in one of her first-year seminars.

“My students were immediately, entirely engaged in the course. I had virtually perfect attendance,” says Dr. Walker. “They were coming to all the classes; they were doing the readings and they understood conceptually what we were trying to achieve.”

Navdeep Dhillon, a third-year neuroscience and biology undergraduate student who took Dr. Walker’s course as an elective, spoke positively about how RTTP provided an immersive and educational experience, and promoted collaboration between students.

“It was definitely a better way to learn history than I had previously encountered,” says Ms. Dhillon. “Traditional history teaching methods that I’ve encountered are moreso lecture-based and [they’re] very content-heavy and can sometimes blend together and become just names and dates.”

The game helped Ms. Dhillon learn more about her character – American civil rights activist W.E.B Du Bois – as more than just as a historical figure from a textbook, but as a person. “That kind of made them a bit more human rather than just something you’re reading out of a textbook or hearing from a lecturer.”

In 2019, Dr. Walker started working with Martha Attridge Bufton, an interdisciplinary studies librarian from Carleton who has an interest in game-based learning and was intrigued by the immersive role-playing methodology of RTTP. Their collaboration led them to create a new role for academic librarians, which they applied in the game Greenwich Village 1913, with Ms. Attridge Bufton playing and acting as Maud Malone, a New York City librarian, suffragette and labour activist. As Maud, she helped students understand key historical questions and conduct library-based research.

Their contribution to the game series was noticed by the Reacting Consortium and awarded its first Brilliancy Prize for Reacting.

“Both Pamela and I were really pleased to win the Brilliancy Prize for Reacting,” says Ms. Attridge Bufton. “This recognition confirmed that we were on the right track in terms of doing good pedagogy but also making an original contribution to this historical pedagogy.”

Dr. Walker has recommended RTTP to many of her colleagues, but also added that it is not for everyone, nor is it for every subject.

“You have to have a certain amount of self-confidence or moxie even to do this because it requires that you do something that your students are not expecting,” says Dr. Walker.

This is a great article that shows a way professors can move learners to at least the “demonstration” level (30%) of the Learning Pyramid, and perhaps to the Pyramid’s “discussion” level (50%), and quite possibly to the Pyramid’s “Practice by doing” (75%) learning level. It also reveals an excellent use of a librarian’s skills in the teaching and learning process. Except for one memorable professor whose infusion of details and personality traits of historical characters he included in his lectures, I remember history class “blending together to become just names and dates.” RTTP games appears to be an excellent teaching and learning strategy.

One change I do hope educators will begin to make to explore the benefits of employing “andragogy” rather than “pedagogy.” College students are not children; typically, they are young adults. My experience has been that Knowles’ Adult Learning Principles are useful when determining how to implement new teaching strategies. It could be that other subjects would benefit from RTTP-like games if one considers the practice of andragogy rather than pedagogy. I believe the idea that “adult learning” refers only to older adults is outdated.

There is an excellent explanation on the difference between andragogy and pedagogy and the benefit of using each at https://elmlearning.com/pedagogy-vs-andragogy/. During my doctoral research, I found the differences and benefits to be clear and distinct, and it doesn’t hurt that Knowles’ principles have existed since the 1950s. In this time of profound changes to teaching and learning methodology, it seems that our educational literature could also begin to reflect a profound change.