A U.S.-based publishing-services company, Cabells International, has launched a blacklist of what it calls “deceptive” scholarly journals. The new blacklist, launched on June 17 and available only by subscription, is being described as a replacement for Beall’s List, which was a list of “potential, possible or probable” predatory publishers created by Jeffrey Beall. A librarian at the University of Colorado Denver, Mr. Beall coined the term “predatory publisher.”

Mr. Beall’s famous, but controversial, list included about 1,200 publications and 1,000 publishers. However, he abruptly deleted his list in mid-January, partly because he was worn out by publishers who threatened him and harassed his colleagues, he said. Also, in a recent article in the journal Biochemia Medica, Mr. Beall wrote that he’d received “intense pressure” from his university about the list and, “fearing for my job,” he shut it down.

Kathleen Berryman, senior project manager at Cabells, said her company had discovered Beall’s List a few years ago and used it to help clean up their whitelist of 13,000 reputable scholarly publications (a whitelist names publications that are considered legitimate, while a blacklist lists those judged to be suspicious).

However, she said the company soon realized that academics needed a bigger, companion blacklist to track the skyrocketing number of deceptive journals. Its website quotes researchers from the Hanken School of Economics, in Finland, who noted that the number of articles published in about 8,000 predatory journals jumped from 53,000 in 2010 to an estimated 420,000 in 2014.

“Deceptive journals are a very huge threat to science,” Ms. Berryman said. “They do a lot of damage to researchers and readers, because of fake data and the nonsense that the journals publish. People run with this data and info, and act like it’s true.”

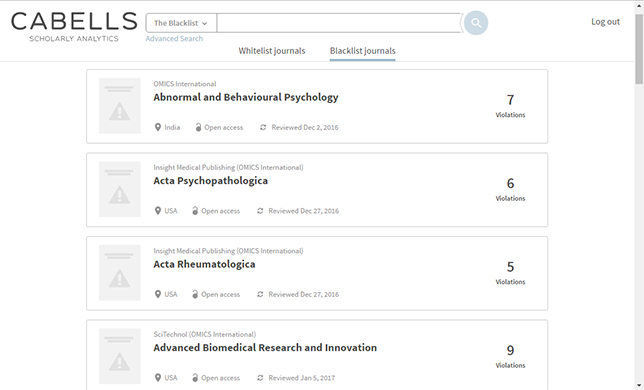

Now, after investing hundreds of thousands of dollars and one-and-a-half years of work, Cabells has launched the Journal Blacklist, Ms. Berryman said. The inaugural list contains nearly 4,000 deceptive journals. “We’re getting away from the word ‘predatory,’ and we’re using ‘deceptive,’ because ‘predatory’ has become misunderstood,” she said.

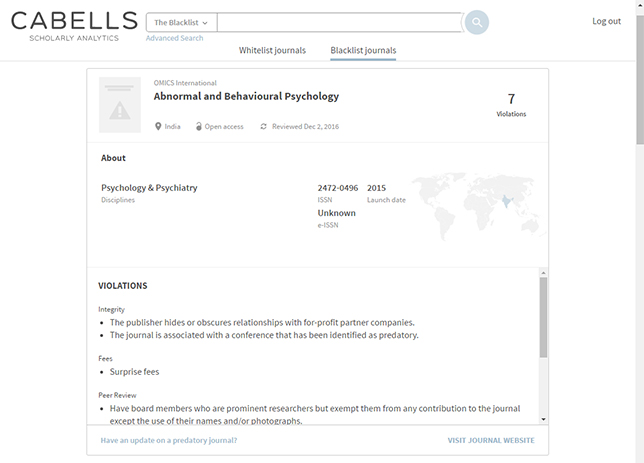

The Cabells list uses 65 criteria, each of which is assigned a certain number of points, to determine a journal’s legitimacy. A journal website with spelling and grammar errors wouldn’t accumulate many points, for example, but evidence of plagiarized articles or lack of peer reviews would rack up more points. (See sidebar at the end for more criteria.)

“We have developed … an objective, transparent process, and we excluded opinion-based decisions,” Ms. Berryman said. Beall’s List had been criticized for relying on too much opinion from a single individual in deciding which journals were predatory.

The Cabells list includes only what it deems to be deceptive journals, as opposed to merely mediocre ones. “More and more reputable, mainstream publications are publishing mediocre or low-quality journals, but we don’t include them on the blacklist,” Ms. Berryman said. “We focus on deceptive journals.”

The list also doesn’t include journal publishers. “Many legitimate publishers may also have journals that are deceptive, so by focusing on journals, not publishers, that allows us to include them,” she said. The list includes both subscription-based and open-access journals.

Each journal on the blacklist is accompanied by a list of its violations, so, at a glance, readers can see exactly why a journal landed there. Some of the reasons are obvious (such as stealing the name of a legitimate journal), while others are more subtle (such as a lack of policies for the digital preservation of articles).

Cabells also has an appeals process that allows journals to apply to be removed from the list, with the onus on the journal to prove that it’s making honest efforts at addressing the violations. “These [appeals] may take a long time to follow up, especially if we look at things like the peer-review process,” Ms. Berryman said. “We have four staff people who check the journal’s claims and revisions. We sometimes contact editorial board members and authors, which is particularly time-consuming but also important, because deceptive journals are known for using academics’ names without telling them.”

The new blacklist is accessible only by subscription. Ms. Berryman said the main subscribers are universities and research companies, with the price based on a sliding scale that depends on the size of the institution or company. She refused to give the price range, saying that institutions can receive estimates directly from Cabells. Beall’s List was free, and reportedly received up to 20,000 pageviews a day.

David Moher, an associate professor in the School of Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventative Medicine at the University of Ottawa, runs the Centre for Journalology at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and has been researching predatory journals for the past three years. He said he’s concerned that Cabells is charging people to access the blacklist. “In a culture moving fast and furious to open access, it’s unfortunate that people have to pay. University libraries are unlikely to be able to pick up the tab. They’re already under fiscal pressure.”

“Our initial plan was to offer it for free,” Ms. Berryman explained, “but as time and resources grew, we realized that wasn’t sustainable.” However, she said the company hopes that the list will be freely available one day.

Marc Couture, a retired professor at TÉLUQ, Quebec’s distance-learning university, said many academics don’t like the unacknowledged subjectivity behind blacklists – or whitelists, for that matter. As well, some of the criteria for these lists “don’t fit well with the reality of small social science and humanities journals, especially criteria that require fees or investment of time,” he said. “A small journal’s presence on a blacklist (or absence on a whitelist) must be interpreted with caution.”

But he is supportive of the new Cabells initiative. “What I like about Cabells is the transparency of the criteria,” he said.

Nevertheless, cautioned Ms. Berryman, “A blacklist is only one solution to addressing deceptive journals. It’s going to take the whole academic industry to address them.”

Some of the 65 criteria used to evaluate a suspected journal

Integrity:

- Hijacked journal (defined as a fraudulent website created to look like a legitimate academic journal for the purpose of offering academics the opportunity to rapidly publish their research for a fee).

- The journal or publisher claims to be a non-profit when it is actually a for-profit company.

- The journal gives a fake ISSN.

Peer review:

- No editor or editorial board listed on the journal’s website at all.

- Editors do not actually exist or are deceased.

- The journal includes scholars on an editorial board without their knowledge or permission.

- Inadequate peer review (i.e., a single reader reviews submissions; peer reviewers read papers outside their field of study; etc.).

Website:

- The website does not identify a physical address for the publisher or gives a fake address.

- Dead links.

Publication practices:

- The journal publishes papers that are not academic at all; e.g. essays by laypeople or obvious pseudo-science.

- Falsely claims indexing in well-known databases (especially SCOPUS, DOAJ, JCR, and Cabells).

Indexing and metrics:

- The journal uses misleading metrics (i.e., metrics with the words “impact factor” that are not the Thomson Reuters Impact Factor).

Fees:

- The journal does not indicate that there are any fees associated with publication, review, submission, etc., but the author is charged a fee after submitting a manuscript.

Access and copyright:

- States the journal is completely open access but not all articles are openly available.

- The journal publishes not in accordance with their copyright or does not operate under a copyright license.

Business practices:

- Emails from journals received by researchers who are clearly not in the field the journal covers.

- The journal has been asked to quit sending emails and has not stopped.

Encouraging a culture of open critique of individual papers no matter where they’re published is more valuable to science than any concept of blacklists or whitelists which are really just apologists for hierarchical and non productive academic practices. They simply feed into publishing oligopolies and worse, justify institutional monopolies on elite output forums.

My general opinion on Cabells’ blacklist, and on blacklists in general, is accurately portrayed in this article. I would nevertheless like to add some further explanations.

1. By “transparency of the [Cabells’] criteria”, I meant not only that the list of criteria is publicly available but, more importantly, that the specific criteria which led to the inclusion of each journal are also available (as far as I can tell from what is found on Cabells’ website, not having access to the list itself). Other blacklists, like Beall’s and DOAJ’s (which hosts a list of nearly 2000 journals removed for “not adhering to best practices” or “suspected misconduct”, http://bit.ly/1cPK4Lr) also make their criteria available, but the detailed reasons for the inclusion of each journal (and publisher, in the case of Beall) are hard to find, if disclosed at all.

2. Cabells’ blacklist uses about the same number of criteria than Beall’s (~ 60). While the majority are equivalent or similar to those of Beall, some of the more questionable or fuzzy among the latter were not retained. However, in the whole, Cabells’ criteria still cover a large spectrum of issues, ranging from outright dishonesty or misinformation to arguably sub-optimal practices. Some of these, notably in the case of small journals, are more a consequence of limited resources than of lack of rigour or intent to deceive. This is one reason why a detailed justification of inclusion for each journal is important, as it helps researchers make their own judgments – as they always should do anyway – on the suitability of the journal.

3. I concur with David Moher that a main drawback of Cabells’ list is its paywall. This is particularly important if one considers the well-documented issues of the use of so-called “predatory” journals by researchers from emerging countries. It could well be that those who most need the list will be the less able to access it.

Finally, there has been much debate on the importance – both in terms of number of papers and of global influence on scholarly publishing – of the phenomenon of “deceptive” journals (a more appropriate qualifier than “predatory”). One can only hope that Cabells’ initiative will help us progress towards a more nuanced perspective. For instance, I strongly suspect than the number of papers published annually in truly deceptive journals will be much lower than the figure mentioned in the article (420 000 papers in Beall’s list journals), which is itself disputed (see http://walt.lishost.org/2017/04/the-problems-with-shenbjorks-420000).

Interestingly, Cabell’s International website does not identify a physical address. Can we consider it a deceptive company?