How a set of nearly 400-year-old Italian instruments ended up at the University of Saskatchewan is a story true to the can-do nature of the Prairie province. In 1959, local grain farmer Steve Kolbinson came to the school’s music department with a stunning donation: a viola, cello, and two violins, forming what’s known as the Amati quartet. Fascinated by string instruments, Mr. Kolbinson spent years travelling in search of rare ones. He was also good friends with Murray Adaskin, a renowned Canadian composer who then headed the university’s music department.

The instruments have been brought out periodically, but this fall the university launched its first dedicated concert series to honour them. “Discovering the Amatis” came out of a collaboration between violin professor Véronique Mathieu and musicians from around Saskatchewan. “One single Amati instrument is rare, and to think that there are four of them together, it’s almost unheard of,” said Dr. Mathieu. University president Peter Stoicheff said in a statement that Mr. Kolbinson wanted to see the instruments used “in ways to benefit the people of the province,” noting that the concerts are open to the general public.

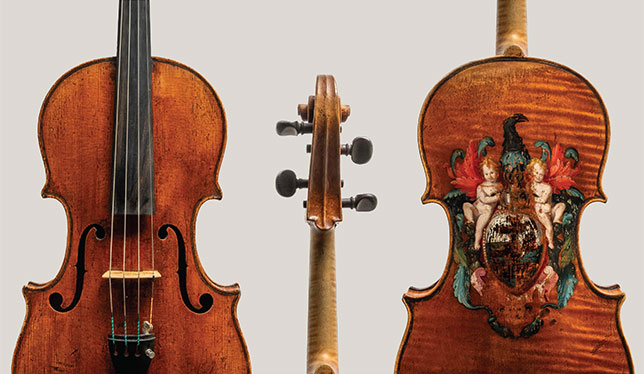

The instruments were handcrafted in the 1600s by members of the Amati family in Cremona, Italy. Their story overlaps with crucial historical moments, even landing in the hands of the famous Borghese family. Cellist Simon Fryer, who played in the October concert, called the Amatis “tremendous pieces of history.”

Dr. Mathieu, who holds the school’s David L. Kaplan chair in music, has wanted to design concerts for the Amatis since starting in her role five years ago, but the pandemic stymied her plans. When restrictions eased she started small, having one or two of the instruments played at specific areas around campus, which she termed “noon hour” concerts. she would discuss the history, answer questions, and afterwards, the instruments would stay out on display. “People could actually come and see them close up – it was a nice opportunity for everyone,” she said.

Given their significance, it would be understandable to want to approach the instruments with delicate hands – but Simon Fryer, a cellist from the Regina Symphony Orchestra (RSO) says some music “requires you to lay into the instrument quite heavily.” Mr. Fryer, who played in the Oct. 23 concert, described the Amatis as “tremendous pieces of history,” pointing out that they were crafted in the so-called “Golden Age” of string instrument making. He said practising with the cello was “very much like meeting royalty.”

Christian Robinson, a violinist with the RSO who also played in the October concert, said working with the Amatis was a lesson in skill. “With stringed instruments, everything is very tactile, and the way that you draw a sound out of the string is very personal,” he said. “Each individual instrument has its own personality.”

As concertmaster, he chose a contemporary piece by Canadian composer Dinuk Wijeratne alongside Beethoven, a thematic reflection of the experience. “It worked well with this concept of the old and the new, and the collision of those two things. It seemed really appropriate to incorporate that on these old instruments.”

Dr. Mathieu ensured the concerts would be intimate, as the Amatis were originally meant to be heard in that type of setting. She also helped select music that would be recognizable to a wider audience, upholding Mr. Kolbinson’s goal of having the instruments accessible to the general public (the RSO was also given the opportunity to play the Amatis at Saskatchewan’s Government House). “Even if we have a program with all these exciting concepts, if there’s no audience, then there’s no concert,” Dr. Mathieu said.

She has a vision of future concerts that reflect and trace the Amatis’ unique story – music from Italian or French composers – and perhaps one day an in-house quartet to play them regularly.

The public can see the Amati instruments for their next planned concerts on Feb. 5 and April 23, on the USask main campus.

Very heart-warming! Bellissimo!