You will have to bear with me. I am both a Canadian and an American citizen. I am also an inveterate reader of The New Yorker magazine, whose weekly arrival I look forward to but never seem to catch up with. Inevitably, the stack grows and I wait for the lull of the holidays to read through them. This year my stack dated back to early November. Sitting down to read them reminded me where I was during the weeks before and after the U.S. presidential election.

On election night I was in Ottawa at the Canadian Science Policy Conference, where colleagues and I watched the results. Confronted by an unexpected new reality, I began to wonder what it meant for our universities.

A little over a week later, I was with fellow panelists of the Advisory Panel on Federal Funding of Fundamental Research. Anne Wilson, a panel member and astute social psychologist from Wilfrid Laurier University, suggested we read American Amnesia, a book by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson (co-director of the CIFAR Successful Societies Program). The book sketches out the socio-political process that has contributed to the public’s rising distrust in government and suspicion of “elite” thinkers which have set the stage for the recent election’s surprising outcome. Dr. Wilson reminded us that a similar phenomenon could happen here in Canada and queried how we could keep our universities relevant and understood to be useful by the electorate.

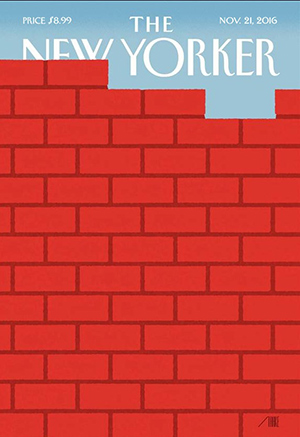

I promptly, thereafter, buried these thoughts under holiday merriment until late in December, when I began my vacation reading with a mind piercing short piece by Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard University. Hers was one of 16 brief reactions to the election in the November 21 edition of The New Yorker. Dr. Lepore wrote, “Many Americans [have] lost faith in a government that has failed to address widening inequality, and in policy-makers and academics and journalists who have barely noticed it.”

I promptly, thereafter, buried these thoughts under holiday merriment until late in December, when I began my vacation reading with a mind piercing short piece by Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard University. Hers was one of 16 brief reactions to the election in the November 21 edition of The New Yorker. Dr. Lepore wrote, “Many Americans [have] lost faith in a government that has failed to address widening inequality, and in policy-makers and academics and journalists who have barely noticed it.”

By January 10 (and several New Yorkers later), I heard outgoing President Obama also invoke our universities’ responsibilities to engage when he said, “For too many of us it’s become safer to retreat into our own bubbles, whether in our neighborhoods, or on college campuses … surrounded by people who look like us and share the same political outlook.” By now, I had started to think hard about how universities are implicated in the state of North American society, and about what we need to do to address what was staring us in the face come inauguration day.

As universities, we are clearly facing a challenge. We need to ask ourselves how we will make our teaching and research relevant, understood and useful to people on both sides of the inequality gap, as well as what to do about that gap. People need to know and understand how what we do is related to their well-being. We need to educate our students to understand fact from fiction, to produce and interpret evidence, to grasp social inequalities and where they come from, to value diversity and – last but not least – to prepare them for an ever-changing job market.

This brings me to another holiday read, Elizabeth Kolbert’s article, “Our Automated Future,” with the subhead, “How long will it be before you lose your job to a robot?” (New Yorker, December 19 and 26 issue). Canadian researchers have become among the world leaders in artificial intelligence, the very science whose impact Ms. Kolbert describes in her article. She demonstrates how these new and exciting frontiers of knowledge have, perhaps unintentionally, led to job stagnation for the very middle class voter who has become disenfranchised from academics and other elites.

On the flip side, we are in an era of fascinating and exciting innovation that has the capacity to improve many aspects of peoples’ lives. Yet, some of these inventions have made a relatively small group of people very wealthy while others lose their jobs. In his farewell speech, Mr. Obama said, “The next wave of dislocations won’t come from overseas, it will come from a relentless pace of automation that makes a lot of middle-class jobs obsolete.” This led me to two simple-minded questions: When robots take over jobs, will they pay taxes? And, if not, how will our governments afford research funding, never mind health care?

My holiday reading has left me convinced that, for the citizenry to elect politicians who are dedicated to the cause of university education and research, we need to make our work, our ideas and our campuses accessible and meaningful to all, not just our students and ourselves. We need to become aware of the social realities that set us apart from many of our fellow citizens and address them.