Many of us have had the frustrating experience of being in a crowded doctor’s office, or the emergency department, waiting hours for test results or trying to coordinate a family member’s care. Such issues arise because the medical experts who created our health-care system to heal patients don’t necessarily possess the lived experience of the health care system. These issues can be addressed by listening to patients – but even better, by having patients and their caregivers at the decision-making tables.

For example, the Ontario Government has a Patient and Family Advisory Council designed to give personal and professional advice to government on key health-care priorities. With such advice in hand, the system can change for the better, including improving patient safety, making sure programs reflect patients’ needs, and improving how patients and their families access, understand and use health information.

Similarly, we need students at the decision-making tables in higher-education, especially as we contemplate summer and fall semesters of COVID-19 impacts. Students experience that system; they are the principal stakeholders and stand to benefit (or be harmed) the most from the quality of their educational experience. For example, they know best the experience of navigating program and course choices, ways to communicate with each other, and the learning challenges they face in this pandemic situation (Figure 1). They are not experts in the subject matter, but they are experts in the system. We need their expertise at the table to design the best possible education system.

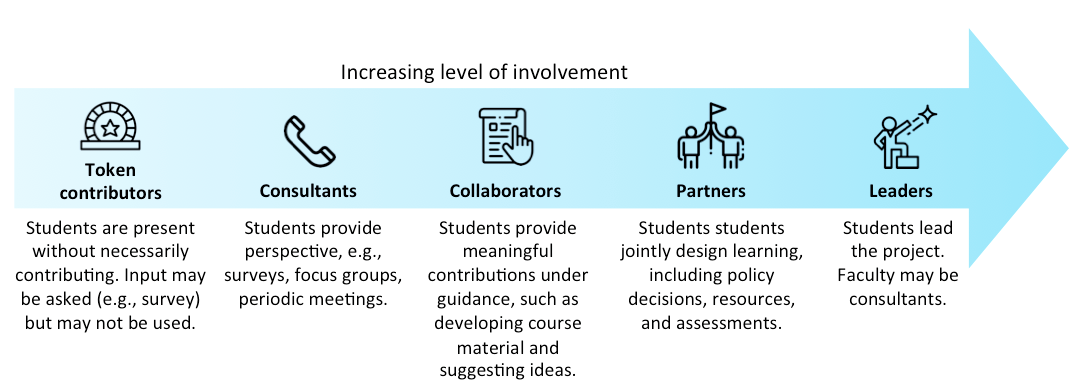

There is a range of ways to bring students to the table as consultants, partners and leaders (Figure 2). Students can be included by sending out simple surveys asking for suggestions and information, such as “What should the instructor (1) start, (2) stop, and (3) continue doing in this course?” or “What has happened in the (1) best and (2) worst courses you’ve taken?” Alternatively, teaching assistants in your courses can act as collaborators or partners, helping to design a new format for the course, develop course materials (e.g., videos and problem sets), or act as facilitators for class discussions (synchronously and asynchronously). Students can also join the decision-making tables for department, faculty and university-wide committee meetings as partners as new policies are being made on a host of issues, including educational equity, assessments, communication and mental health.

In our own work, students have been a part of every development and research team in every type of role. We have also consulted with students early and often throughout projects. For example, in our Growth & Goals module, our original prototype of an outside-the-course workshop became an integrated course module following student consultation. Moreover, a mature student as a partner on the project brought the perspective of how the module could benefit not only in the academic setting but also in the professional setting beyond.

Other groups have student leaders to develop and prototype solutions to problems in the system, as identified by students. For examples, eCampusOntario’s SXD lab “uses human-centered design processes and tools to (re)design better student experiences. We do this by working with the end users of education: students. We hire, train and coach students from across Ontario to conduct user research, define specific problems, generate and test ideas, and develop innovative solutions with institutions and industry.”

The results are better when students are at the table: the work goes faster, and students think of ideas that professors would not have thought of alone. Professors benefit from new, more relevant materials for their courses as well as enhanced relationships with student partners. Students themselves directly involved in partnerships leave those partnerships with new skills and ways of thinking, including greater metacognitive skills. Research has found that students leave partnerships more engaged, motivated, and take more ownership for their learning. There are still more benefits, including improvements to faculty’s teaching and students’ perceptions of learning, helping future students, and creating inclusive communities.

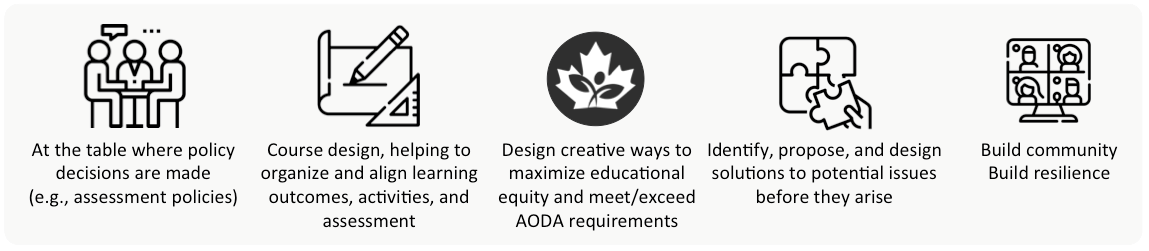

With the upheaval brought on by the global pandemic, we need student partners more than ever. We are having to dramatically rethink the ways in which we teach our courses. For the majority of us, these courses will be remote courses (very different from carefully designed and constructed online courses) and students can be involved in many ways (Figure 3).

Students can be partners at the tables where policy decisions are being made, such as assessment policies. Students can be partners in course design, helping to organize and align learning outcomes, learning activities and assessment. Students can help design creative ways to maximize educational equity and meet (or exceed) Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act requirements, including identifying options to support student learning through this pandemic. Students can identify and propose/design solutions to potential issues before they arise within the course itself. Students can connect with other students, helping us build our community and resilience through this challenging time.

Including students is easy and the benefits they bring far outweigh any lack of expertise in a given subject. Let’s get our key stakeholders to the table so that we can make education better.

Alison B. Flynn is a 3M National Teaching Fellow, member of the Global Young Academy, and an associate professor in the department of chemistry and biomolecular sciences at the University of Ottawa.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to the following artists for the icons from flaticon.com used in this article: Freepik, Becris, dDara, Srip, and Nikita Golubev.