Remember when hardly a week went by without headlines in the media proclaiming a “Trump bump” was driving droves of international students to swarm university campuses in Canada? That was the seemingly distant 2017, when a welcoming and gentle Canada was opening its arms to the world’s brightest, as the Trump administration instituted travel bans, set out to build walls, and stoked the flames of xenophobia.

Although we did not have the official numbers – courtesy of our morose national effort at collecting and disseminating postsecondary education statistics – journalists, university associations, and admission officers were ready to stoke the fire on this narrative. “Trump is turning Canada into a haven for the world’s best and brightest,” proudly shouted out Maclean’s magazine. “Applications from international students were up by double digits this year, with record levels of interest from American students,” reported the Globe & Mail. TVO ran a 40-minute The Agenda debate on how Ontario universities benefited from the “Trump bump.”

The narrative was not lost on international observers, and certainly no greater satisfaction was enjoyed domestically than from the recognition of Canadian virtue and triumph by American news media, with coverage of the “Trump bump” from the New York Times to Vice indulging the national character.

Invited to speak at an international education seminar during that summer at Boston College, I discussed my skepticism about this narrative based on my research on international student mobility, to my audience’s surprise. Basically, it is too simple and too fast. There are usually multiple factors at play influencing the choices of international students, and long-term considerations are as relevant as short-term events. This is, of course, the antithesis of media-friendly sound bites – such as, say, the “Trump bump.”

It turns out that there was no “Trump bump” after all.

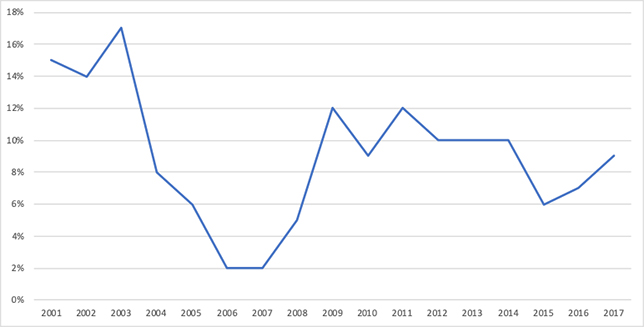

The most recent international student enrolment figures released by Statistics Canada show two things. First, the unfolding of a long-term pattern: international student enrolment has been growing relatively steadily since the late 1990s in Canadian universities, approaching 200,000 students in 2017. Second, the nine percent annual growth in 2017 is rather ordinary; it is the actual average rate of growth since 2000.

Had there been a “bump” of any kind since Trump’s election, we would expect to see an increase in enrolment that goes above and beyond the usual growth that we have experienced for two decades, not simply any growth. Because for many other reasons, our campuses have been welcoming more international students in greater number for many years. Instead, the 2017 growth rate is lower than those of most years during President Obama’s administration, for example.

It is quite possible that the picture has changed in the intervening years. But again, we will not know for sure until Statistics Canada releases updated figures in another year or two. And in the absence of data, stories like the “Trump bump” can easily take on a life of their own, built on facile narratives that many people are eager to believe in.

Considering Trump only took office in 2017, and the matriculation cycle can take a year to show up, don’t you think drawing this conclusion from data that stops in 2017 is a bit premature? The Trump Bump may well show up in the 2018 and 2019 data.

Also there is a difference between application data and enrolment data. Many programs, like our nursing and veterinary ones, have caps that are always met. We may get double the number of applicants, but our enrolment will stay flat – the difference will be in the increasing competitiveness and therefore quality of admitted students. We also may choose not to increase the ratio of international to domestic students, or not to do it so fast as to overburden the special services that international students require. So again, the bump may show up not in total enrolment but in selectivity/quality of international students accepted.

Maintenance of a long term average growth rate with a larger base over time suggests a “bump” occurred in absolute enrollment of international students. Also, perhaps a better of measure of whether a “bump” ocurred is the change in applications from international students, particularly those disdvantaged by American Visa policies. Given enrollment is at capacity for many Canadian institutions and the policy for % of seats allocated to international students does not necessarily change in proportion to change in applications, then it would be reasonable for a scenario where there indeed was a bump in demand but not propertionately in supply of seats at Canadian universities. Would be interesting to look at issue from that lens.