In one of my earlier posts, I mentioned that the Ontario government had released a discussion paper on postsecondary education in the province. Following this release the Minister for Training, Colleges and Universities, Glen Murray (MPP for Toronto Centre), has been seeking feedback on the ways in which Ontario should change its PSE system.

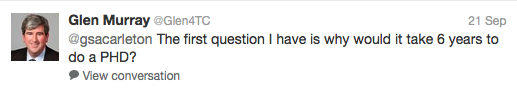

What kind of feedback is the Minister seeking? Well, here’s one query that hit a nerve on Twitter:

I admit I was somewhat taken off-guard by this. Assuming the Minister is familiar with the doctoral education process (in North America) and what it entails, he already knows that it’s longer here than in European countries, for example, where length is more like three to four years and there is no coursework. Coursework alone tends to last a full year in the Canadian PhD, and can extend into a second year if anything goes “wrong”.

Depending on the program and area of study, after coursework students must complete comprehensive exams, a dissertation proposal, and then the dissertation itself; the time can start to add up. In some U.S. doctoral programs, including at prestigious institutions, “standard” times to completion can be seven or more years given that there may be requirements to work in multiple languages (depending on disciplinary area). In Ontario six years has become an optimistic maximum, but have we really examined how and whether (and which) students are finishing their degrees in this amount of time?

Speaking of things “going wrong”, even if we set aside the academic requirements–which are demanding–we cannot assume the “ideal” conditions for students’ completion. For example, my coursework time was extended because of a three-month strike at York University (and for other reasons as well). In the PhD “schedule” there’s already little or no room for illness or accident, for mental health issues, a divorce or a death, the birth of a child, a bad or wholly inattentive supervisory relationship, vicious or destructive departmental politics, or any of the other serendipitous twists and turns that affect all levels of education but which are so poorly accounted for in much of our policy.

Another, related question I would ask is this: does the Minister have access to Ontario’s doctoral attrition rates, and if so, is he asking questions about those as well? PhD non-completion rates are notoriously high in the United States and the few numbers being batted around suggest that rates may be similar in Canada. We need to start taking a hard look at these numbers and ask, in which programs are students graduating and why?

We should also think about the fact that some of the most helpful feedback could come from past students, those who graduated but also–perhaps more importantly–those who didn’t. I don’t know of any PhD programs that use exit interviews with the students who didn’t complete their degrees. Yet this information is invaluable in assessing policies and practices in doctoral education. We need to know what can go wrong as well as what “works”.

Apart from the qualitative information, we also lack recent and comprehensive quantitative data. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, the Canadian government has either suspended or cut the major surveys such as the Survey of Earned Doctorates (the last cohort represented in this Ontario report, graduated in 2005).

Most of all, we need to take apart the idea that PhD outcomes are the result of selecting the “right” students who have enough “merit” and who work hard enough. There is research, mostly from other countries (again: we need more Canadian work on this), that suggests these aren’t the main determinants of PhD completion–but that faculty often assume they are. It’s not as if students don’t want to finish or lack the intelligence and stamina; but there’s more to it than just wanting, and that’s the part we need to figure out.

If one goal is to reduce the time it takes to complete a PhD, then clearly there’s a need for governments to engage in close consultations with PhD students (and former students), graduate program directors and faculty, and deans, in order to get a sense of what kinds of interventions and policies might help. I hope that’s what will happen before changes are made to Ontario’s approach to doctoral education–and this will be especially important considering the ongoing increases to graduate enrolment in this province. Otherwise, we are shooting at a moving target–in the dark.

PhD takes 6 years to complete because you need to collect data. For me, I’m beginning my fourth year and the major phase of data collection, and it would take me at least two years (one calendar year if I’m lucky and extremely aggressive) to collect enough data to answer the questions I’m trying to answer. I collected some pilot data before that, but my first two years were mostly dedicated to coursework and “finding an idea”.

I’m a UK graduate and took just over 4 years to complete a PhD (while working full-time for two years of it). I think the North America PhD experience can be both really damaging to grad student careers (as it delays their entry into the academic job market to such an extent that they get trapped in insecure and demoralising contract positions for years) and very beneficial (as it provides time to get some vital teaching, especially lecturing, experience and publications).

Now, one thing I don’t understand about Canada is that if a PhD student in Canada is expected to have a Masters degree before applying for a PhD (and I don’t know if this is the case), then why would they then expected be expected to also complete coursework in the first 1-2 years of their PhD?

To me it would make sense to get rid of those 1-2 years of coursework if a student has a Masters. This is the position in the UK now, where you pretty much need a Masters before you can complete a PhD.

In terms of the length of time needed for fieldwork / data collection to complete a PhD (galpod comment above), I’m guessing this depends on the field of study. It would seem to make sense to me, however, that supervisors strongly suggest that PhD students aim for projects that can be completed in a reasonable timeframe.

Now, this comment is based on the assumption that PhD students are doing their PhD to then pursue an academic career. If it’s more to do with personal interest etc., then all bets are off. But, at a certain point during the PhD it will become increasingly difficult to subsequently find an academic career if a student has spent too long as a PhD student. There is a very real chance that they will simply ‘miss the boat’.

YES YES YES! This issue goes beyond Ontario; Canada as a whole lacks hard data on graduate student attrition and times to completion and really hasn’t a clue as to the reasons why students leave. Let’s get going with the data collection so I don’t have to rely almost entirely on American data and literature in my dissertation, how shameful is that?!

I agree with every single word! In my PhD, for example, two years were practically wasted because the project “went wrong.” And it took a few more months to figure out another research project. With this change, I had to take other courses (one more year!)… And now I just had a child… It’s been 4 years already and only now I can foresee an expected graduation date…

Oh! And how about the supervisors taking months to provide you with feedback so you can move forward?!!??! Anyways, a PhD is much more mountainous that it seems.

The missing element in this discussion is funding for graduate student stipends. In the sciences, most university departments establish a guaranteed minimum stipend based on TA-ships, funds from the Province divided among students, and contributions from supervisor’s research grants. Because the stipend is guaranteed, the student has a reasonable chance to complete a degree with no distractions other than TA-ships. In the humanities, there appear to be fewer financial resources to support students, particularly since grants are not structured in the same way as in the sciences. Thus, doctoral students must take employment, often outside the university, to support themselves, particularly where the cost of living is high. Employment not directly related to thesis work is time not spent doing thesis work (in addition to travel and work-related distractions), and a major obstacle to progress. Picking up the threads after weeks or months off the project, or juggling time and place to do research simultaneously, seriously reduces the value of the time available for research. Until funding for doctoral students approximates the cost of living, doctoral programs will be longer than ideal.