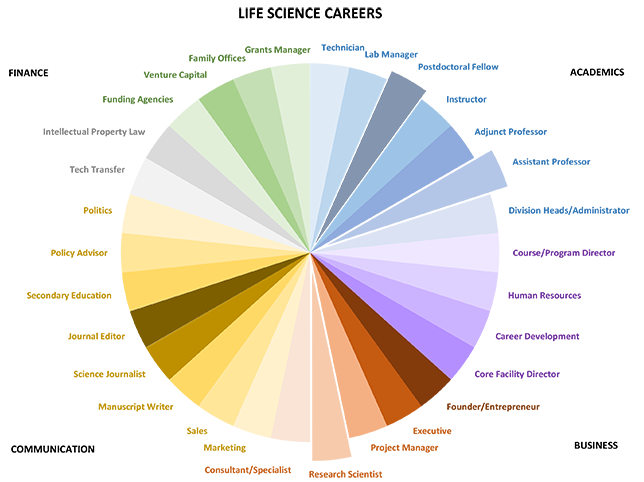

The following is an excerpt from a talk I gave at the Mentor Celebration Event at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA on May 23, 2016. Due to length, I have broken it up into three parts. What follows is the second part.

In the first part, I addressed career options in academe when working in the life sciences:

In this post, I will break down career options in Business, Communication and Finance.

Part 2: Business, communication, and finance

Business

Amongst the most unique career trajectories is that of founder/entrepreneur, which effectively comprises all of the careers listed on this graph under a single title. In the early days of a startup, the founder(s) take on all roles in turn; as the company grows, the burden of each role increases and a dedicated CEO, chief scientific officer, and chief financial/business officer are typically hired, which constitute the executive team. Depending on the number and expertise of the founders, and as the company grows, the executives further off-load some of their responsibilities to new hires. This begins the process of coalescing responsibilities around a specific individual or team, which become further focused over time. The natural evolution of this growth and specialization are large biotech companies, where specific positions become very narrow in scope. Research scientist at a large biotech or pharmaceutical company is what is typically implied when using the term “industry” in relation to career development.

Communication

Supporting the executive team are “consultants/specialists” where I am lumping statisticians, clinical trial designers, regulatory experts and governmental relations, lobbyists, executive consultants and topic specialists (either freelance or at consultant companies). One example are grants consultants that are often hired by private companies to prepare and review federal grant proposals and assist in their submission. In general, consulting tends to be a very lucrative business, and executive consultant companies like McKinsey or Boston Consulting Group often recruit PhDs from major academic institutions, and routinely hold information sessions here to generate interest.

Science communication is of huge importance since it’s quite literally the way we disseminate the work being conducted at primary research and academic institutes to the public, who ultimately finances our work. Most scientists first experience science communication through primary and review manuscripts, as unpaid reviewers for academic journals, and scientific talks (where you are mostly educating other scientists and not the public). Science communication is also a full-time job and can be broken down into a huge variety of independent careers, including marketing, sales, manuscript writer, science journalist, journal editor, secondary education – which is critical if we expect the next generation to understand and build off of our accomplishments, policy advisors, and politics – which is vastly important for the continued health of our country and of which there is a clear dearth of scientists (to our detriment!). As vehicles for science communication continue to grow, so will sub-specialties within these fields.

There is also, of course, law. Employment contracts typically compel inventors to assign their discoveries to their employing institution. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 cemented this practice by also granting ownership of inventions made with federal (public) funds to the research institutions where this work was conducted. With this shift came the growth of tech transfer offices at academic and research institutions, as well as the growing need for intellectual property lawyers. The latter can be particularly lucrative in cities like Boston, where there is a lot of investor capital for the life sciences and numerous strong academic institutions to support a growing private life science sector.

Finance

Central to our social contract is the fact that basic research programs are costly and rely heavily on monies from federal institutions and foundations, as well as private investment from angel, venture, and family offices. Research institutions typically employ grants managers to support applications and manage these funds, as regulations governing these funds are increasingly complex. Likewise, the foundations themselves employ scientists to review, advise, and manage their research investments.

As you can see, there are a lot more career options that just academe and “industry” available to you.