Emphasize this: structuring highly readable sentences and paragraphs (Part 1 of 2)

If your writing is being labeled as ‘too dense’, there are some simple ways to reorder the words in your sentences.

Question:

I’m trying to figure out how to increase the reach of my research in fields related to mine. I think that colleagues in my (highly technical) subfield – EdTech – appreciate my work, but when I look at the papers that cite mine, it doesn’t seem to me that my work is resonating in neighbouring (highly qualitative) fields. I asked a colleague about it and she said she found my writing too dense. What can I do to make my writing more understandable within my discipline as a whole, beyond just my specialization?

– Anonymous, Educational Technology

Answer:

When you’re getting the “too dense” feedback, that usually means that you aren’t using the position of the individual words within your sentences to your best advantage. I expect your writing will become more readable for colleagues within and beyond your areas of expertise if you learn to edit stylistically, for emphasis. My response to this question will be a two-parter, with this month’s column focusing on the beginnings and endings of sentences and paragraphs.

When I perform a stylistic edit, I ensure that the most important content appears at the point of natural emphasis in each sentence and paragraph – that is, at its end.

For an example of how you can use the end of a sentence or a paragraph to emphasize a key point, please re-read the previous sentence.

Stylistic editing – editing for readability, clarityand polish, including editing for emphasis – isn’t taught in most academic programs. Instead, The Elements of Style persists as the most-taught text in universities (according to opensyllabus.org), even though professional editors have long decried that book’s outdated, overly restrictive, inconsistent, rigid and classist stance on what constitutes “good” writing. I also learned a lot from reading technical guides like Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace and Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style.

To reduce the apparent density of your writing, I suggest implementing these two strategies:

1. Bury minor details in the middle of your sentence

Don’t let the end of your sentences fall flat. Avoid ending sentences with:

- Time phrases (“in 2021”; “across the two years of the study”)

- Place phrases (“in Vancouver”; “across Canada”)

- Hedging language (“to some extent”; “in general”)

- Procedural details (“as described above”; “as follows”)

It’s not just that such endings can feel anticlimactic – it’s also that these weak endings make it harder for your reader to pick out and retain the most important information in your writing. Consider, for example:

- Before: “Despite widespread skepticism about game-based learning platforms, longitudinal studies have shown significant improvements in critical thinking skills among middle-school students across Northern Europe.”

Are the most important facts in this sentence that these skills have improved among this student population in this region? Likely not, given the sentence’s opening. Instead, it’s likely that what matters most is that, despite skepticism, studies have found improvements in important skills. So, pick up those unimportant details and pop them into an earlier point in the sentence:

- After: “Despite widespread skepticism about game-based learning platforms, longitudinal studies among middle-school students across Northern Europe have shown significant improvements in learners’ critical thinking skills.”

One grammatical feature all these weak, anticlimactic phrases have in common: they’re all prepositional phrases. If you can’t recall learning that term back in elementary school, it’s OK, because you don’t have know what it means: you can easily identify prepositional phrases using the tool at writingwellishard.com and looking for pink-highlighted phrases at the end of sentences and paragraphs. You can even turn off the non-pink highlighting to focus specifically on this part of speech. This tool enables you to quickly scan and identify sentences and paragraphs that end with prepositional phrases, so you can focus your attention where it is needed most:

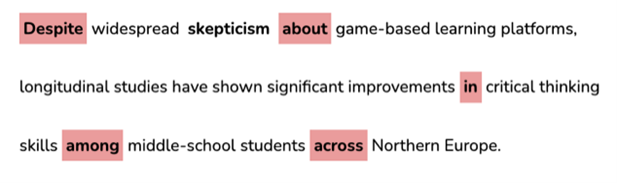

- Before:

Here, you can see two pink-highlighted prepositions near the end of the sentence that both precede unimportant details (a location; the population of someone else’s study), giving us a clue that we might want to bring in a revision.

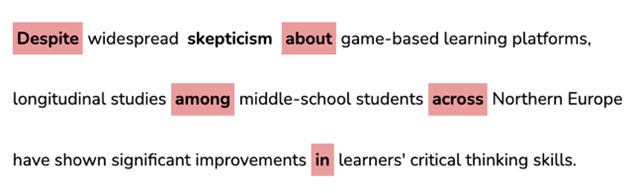

- After:

Here, there’s still one pink-highlighted preposition near the end of the sentence, but because it precedes the most important information – the evidence that counters widespread skepticism – we know we don’t need to bring in an edit here.

Because I designed and host this website, I know that it doesn’t have a back end that stores your data and so won’t harvest your text for some AI-feeding corpus – honestly, I don’t want your draft text; I have no purpose for it; I’m not training any bots. But if you’re generally (and legitimately!) skeptical of claims about data security that you read online, and still aren’t comfortable cutting-and-pasting your text into a textbox, then you’re free to grab the open-source code from GitHub and install your own local version of writingwellishard.com.

One last note: in addition to not ending a sentence or paragraph with an unimportant detail in a prepositional phrase, I also don’t advise ending paragraphs with someone else’s words, as detailed in my November 2018 piece in this column, “Strategic paragraph structuring.”

2. Use right-shifting in topic sentences, to increase emphasis

Now here’s one of those times I love to break the usual “rules” of academic editing. Let’s first establish what the rule is. Many academic editors will recommend cutting phrases like “there is”, “there are” and “it is ___ that.” Indeed, I’m one of those editors – just last September, I suggested that you can cut “is” to shave your word count in character-constricted grant proposals.

But just because cutting “is,” “are,” “was,” and “were” is often a good idea, that doesn’t mean “is” is verboten. So let’s discuss how to “is” with intentionality.

If the end of a sentence or a paragraph is a place of emphasis, we can use “there is” or “there are” at the beginning of a sentence – and ideally, in a topic sentence, at the beginning of a paragraph – to shift our phrasing two words to the right on the page, and thereby subtly increase the emphasis. Here’s the example from Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace:

- Several syntactic devices let you manage where in a sentence you locate units of new information.

- There are several syntactic devices that let you manage where in a sentence you locate units of new information. (Williams [10th Ed.], p. 88)

Starting a topic sentence with “there is” or “there are” can be particularly effective when introducing a complex or counterintuitive concept. By shifting “several syntactic devices” to the right on the page – and, grammatically, from the subject of to an object in your sentence – you’re giving your reader a bit more space and time to process the new context that your paragraph is about to present.

This right-shifting technique can also help create a smooth transition between paragraphs, especially when moving from a broad concept to a specific example, as the “there is/are” construction acts as a gentle bridge that eases the reader into new territory – without needing to awkwardly deploy heavy-handed transition words like “moreover,” “additionally,” “notably,” or “furthermore.” Like the most powerful rhetorical moves, though, this right-shift is most effective when used sparingly.

Remember: The goal isn’t to have a “strong” or “climactic” ending. I know I’ve used those words, but they alone aren’t a justification for this stylistic edit. Instead, your goal here is to structure information in a way that facilitates your reader’s understanding. In educational technology research, dear letter-writer, I expect you often need to describe complex systems and methodologies. For qualitative researchers who don’t work with EdTech, your writing may feel like unfamiliar terrain. Stylistic editing and careful sentence structuring helps readers grasp both individual concepts and their broader significance.

When editing, ask yourself: “What do I want my reader to remember most from this sentence? From this paragraph?” Those concepts belong at the end of each unit of text, sentence or paragraph; that’s where it will have the greatest impact on reader comprehension and retention.

In next month’s Ask Dr. Editor – Part 2 of my response to this letter-writer – I’ll discuss enhancing readability in long and short lists.

Plan ahead to advance your writing practice

This spring, Writing Short is Hard is offering an eight-week facilitated section of “Becoming a Better Editor of Your Own Work.” The course runs from May 4-June 28; the early-bird pricing is available until March 15. Learn more here.

Featured Jobs

- Law - Assistant or Associate Professor (International Economic Law)Queen's University

- Education - Indigenous Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Teacher Education)Western University

- Biochemistry, Microbiology and Bioinformatics - Faculty Position (Microbial Systems Biology, Omics Data Analysis)Université Laval

- Neuroscience - Assistant ProfessorMacEwan University

- Business - Assistant Professor (Digital Technology)Queen's University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.