Rethinking student transcripts to include skill development

Consider UBC dept. of political science’s rich transcripts project.

University of British Columbia political science associate professor Fred Cutler was frustrated with the limited information provided to students on their university transcripts. As he states, “For me the main reason is that students pursue higher education to develop skills more than to assimilate knowledge. And yet the one thing they get to document their studies has abbreviated course titles that are almost all defined in terms of content knowledge.

So he led his department to create something better. The result, the UBC political science rich transcript, provides an exciting example of how the humble student transcript can become a key way of advancing student skill development. In previous columns, I’ve emphasized how one of the big challenges in skill development is helping students identify and articulate the skills they have learned, especially in programs with broad skills training and content learning outcomes. The rich transcript helps them do exactly this.

What are rich transcripts?

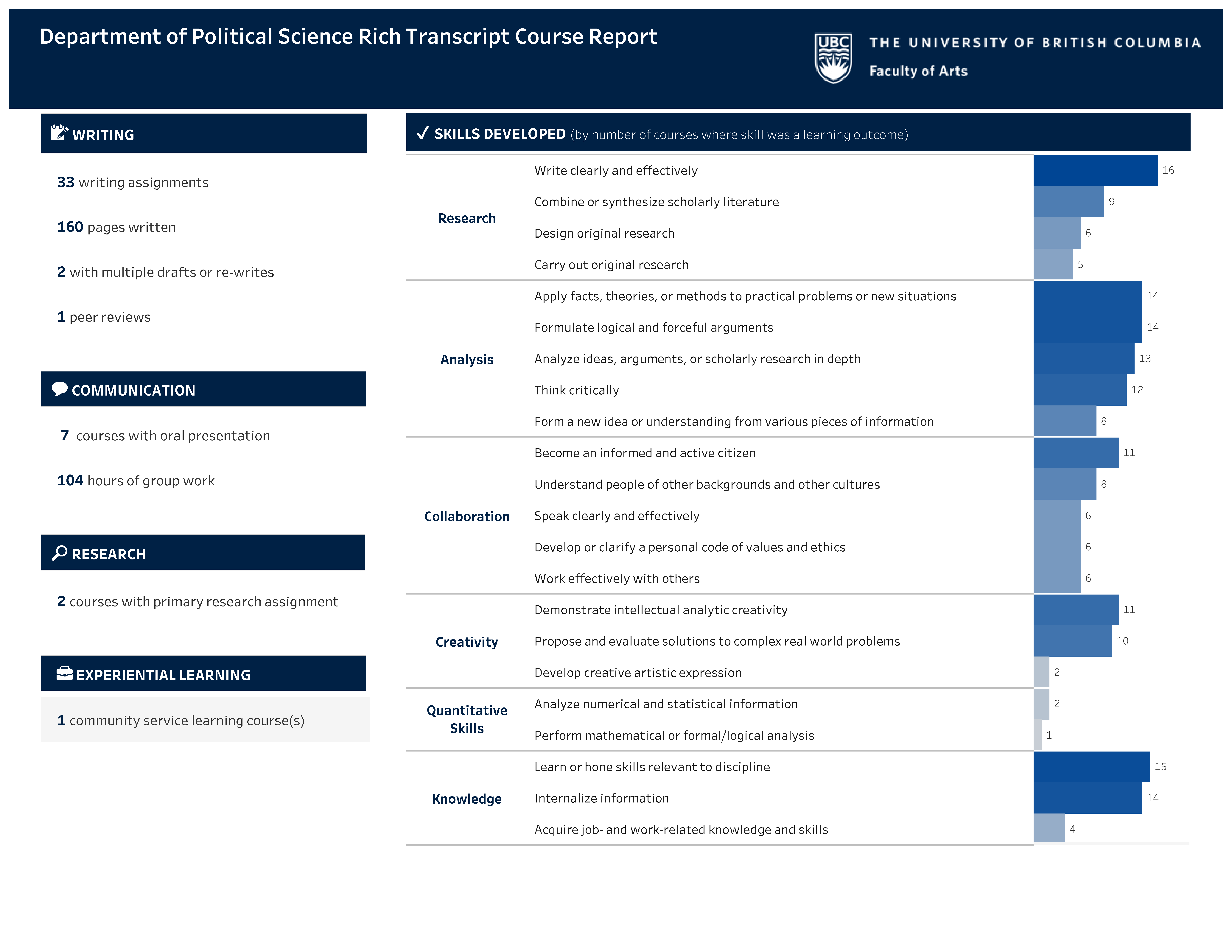

The UBC political science rich transcript is a supplementary student transcript that summarizes student learning in the program. It presents information about all political science classes a student has completed in a visually appealing two-page infographic format.

The first page identifies the political science classes the student completed with their full title (unlike the abbreviated titles found on official transcripts). To capture the content knowledge the student learned across these courses, the rich transcript presents the words in the instructors’ syllabus course descriptions in a word cloud (see Figure 1).

The second page captures a student’s skills training across 23 areas by tallying the number of political science courses a student completed in which a specific skill was one of the course learning outcomes. The rich transcript also identifies the assignment formats a student completed to achieve those skills outcomes, listing (for example) the number of written assignments and hours of group work (see Figure 2).

What is the value of rich transcripts?

Students often struggle to explain to employers the skills they can bring to a job. As Dr. Cutler explains, “In arts programs and courses, there is broad and deep skill development happening, and yet students don’t have something they can refer to when they are asked what they learned to do in their studies.”

Rich transcripts fill this gap. According to Dr. Cutler, “About two-thirds of the students had already shown it to friends or family when we followed up with them a few weeks after they first received it. Sixty per cent said they thought they were likely to show it to a prospective employer at some point.”

And even if an employer may not be able to fully absorb the document on its own, many of the student reactions spontaneously referred to using their rich transcript to identify and articulate their skills. Dr. Cutler reports, “One person said, “I was originally hired as a panel administer for a broadcast measurement company and was promoted in March to a position that requires a lot of writing and teamwork. For my job application and interview, I was able to use the specifics in the transcript to identify what I did during undergrad. Thank you and the department for putting it together!””

Students are not the only beneficiaries of the rich transcripts information. Barbara Arneil, Barbara Arneil, who was department head at the time the pilot was launched, argues rich transcripts are also valuable to departments: “Rich transcripts allow a department head to demonstrate to the dean the level of program quality and pedagogical innovation in a department. That is very valuable.”

What are the lessons from the UBC political science rich transcript project?

In my communications with Dr. Cutler and Dr. Arneil, I drew three key lessons from the UBC political science rich transcript project.

First, university-level initiatives that leave room for unit-specific approaches that suit the particular disciplinary contexts can be valuable to prompt and create space for faculty innovation in skills training. As Dr. Cutler writes, “the faculty of arts at UBC Vancouver was taking first steps into defining program learning outcomes and building a data mart including enrollment and course information. From another angle, the careers and co-op office was looking for more tools to help students articulate the skills they develop in their BA degrees. So the time seemed right to propose a pilot project.”

Second, faculty and department leadership are critical to success. Dr. Arneil spoke to the importance of having a faculty member, and not staff or university administration, driving the initiative. “Faculty are busy and receive many emails and requests. They might not want to be bothered to respond to something external to the department, but Fred is a colleague. Staff can provide critical support but you need a faculty leader to champion the pilot study in order to get faculty buy-in.” Similarly, Dr. Cutler argues that having the full support of the department chair is critical.

The third lesson I draw is the need to identify ways to make data collection for such initiatives easy. While the initial idea had been to code all of the necessary information from course syllabi, this proved inadequate and the team had to develop a new approach. According to Dr. Cutler, “Our estimate is that from start to finish, the project took 400 hours of work by the project team. And then there is the 20 minutes per response for 270 instructor-courses, or another 90 hours.”

That level of labour can be a deterrent, particularly as departments must try to assess the tangible investments (time, energy) against the intangible returns (improved student, employer, and university understanding of a program’s learning outcomes). Dr. Arneil suggests that there is potential to use staff support to reduce the time burden on faculty, if universities wish to provide departments with resources to help. It is also possible that universities could develop or invest in software options that could help automate the identification of skills training.

The UBC political science rich transcript project is inspiring, especially for programs with broad skills training and content learning outcomes that can struggle to help students articulate the skills they have learned. It also shows the advantage of unit-level innovation, allowing departments to construct instruments that fit their context. I hope it inspires readers to think about ways they can similarly equip students.

Continuing the #SkillsAgenda conversation

What are your own thoughts about how universities can identify and communicate the skills that students develop in their programs? Please let me know by commenting below.

I look forward to hearing from you. Until next time, stay well, my colleagues.

Featured Jobs

- Accounting - Tenured or Tenure-Track Faculty PositionUniversity of Alberta

- Electrical Engineering - Assistant Professor (Electromagnetic/Photonic Devices and Systems)Toronto Metropolitan University

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Social)Mount Saint Vincent University

- Indigenous Studies - Faculty PositionUniversité Laval

- Electrical and Computer Engineering - Assistant/Associate ProfessorWestern University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.