Breaking the glass ceiling: Women in Canadian university leadership

Despite making up the majority of faculty, women are still underrepresented among university leadership.

Women have been flocking to Canadian universities in volume since the 1990s. While only 15 per cent of women aged 25 to 64 held a university certificate or diploma in 1991, Statistics Canada shows that this number more than doubled to 35 per cent by 2015. And it’s still growing: by 2021, 41 per cent of women held a degree, 59 per cent of university graduates were women and the majority of students registered in public universities and CEGEPs were women. Yet this trend is not reflected in university leadership. During the 2018-19 academic year, only 29 per cent of tenured professors in Ontario were women.

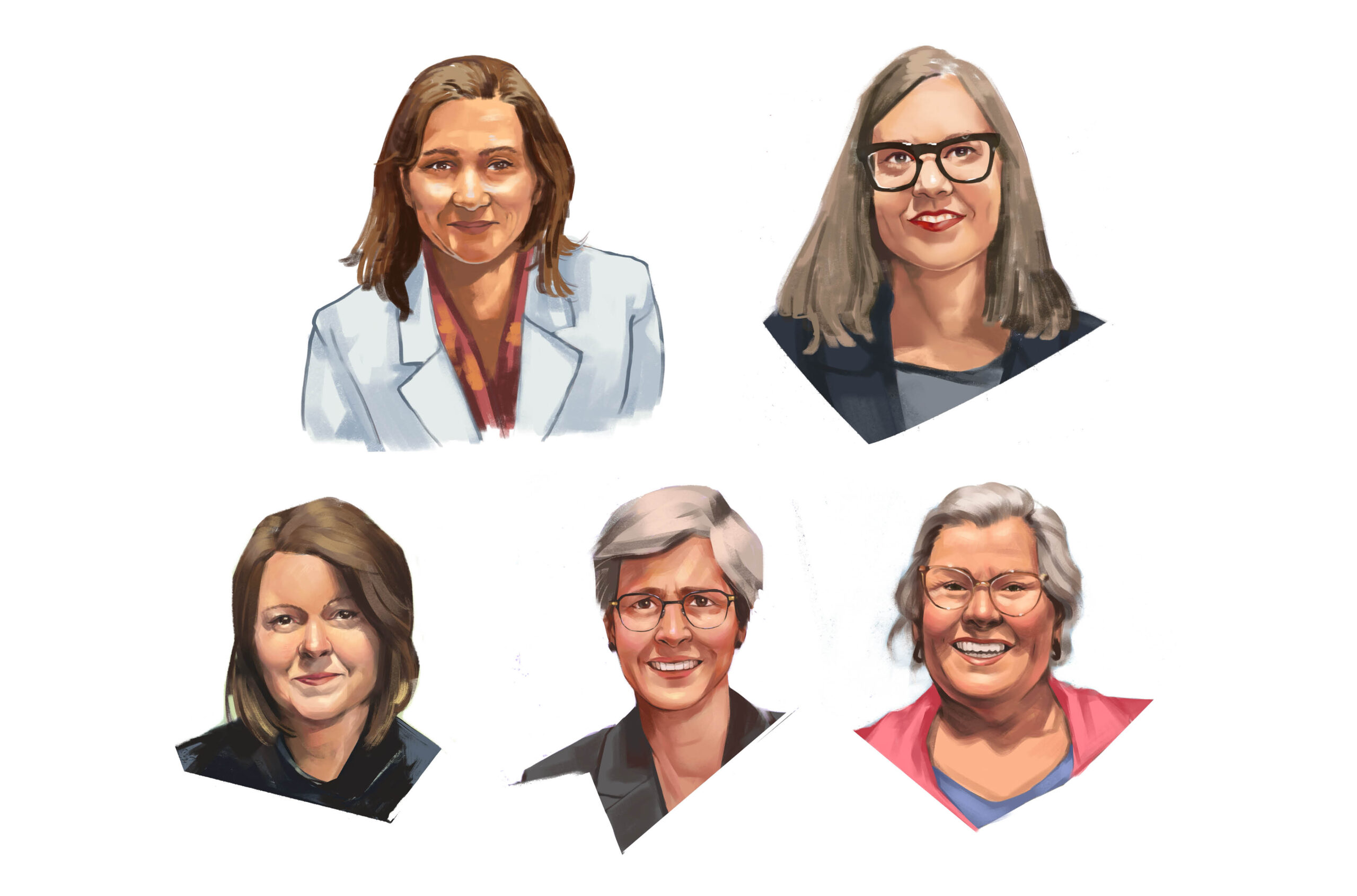

To better understand the challenges facing women pursuing leadership roles, University Affairs asked five female leaders from francophone universities about their experiences: Sophie Bouffard, president of Université de Saint-Boniface; Maud Cohen, president of Polytechnique Montréal; Sophie D’Amours, rector of Université Laval; Murielle Laberge, president of Université du Québec en Outaouais; and Lucie Laflamme, general manager of Université TÉLUQ. They discussed systemic barriers, how far universities have come and how to improve gender equity in university administrations.

Breaking the glass ceiling

Our interviewees agreed that women in leadership roles face persistent barriers. Becoming president in a historically male-dominated environment meant overcoming numerous obstacles, said Dr. Laberge. “Women are in the majority here, and we have many female professors, but I’m the first woman to become president. Men make up the majority on the university’s board. The glass ceiling is still very much in place—and tough to shatter.” Ms. Cohen, the first female president of Polytechnique Montréal, described a similar dynamic at her institution, where certain departments remain male-dominated. “It’s intimidating to take leadership of an institution with such a male background,” she said. “For many women, it poses a mental barrier.”

“The glass ceiling is still very much in place—and tough to shatter.”

Gendered stereotypes can add even more hurdles. Dr. Laflamme recalled a colleague who was reluctant to promote a young pregnant woman. “A colleague said to me, ‘I’d love to promote a young woman to a leadership position, but she’s pregnant. She may struggle to balance work and family obligations, she’ll probably request leave…’” She argued that these concerns would probably never have been raised if the candidate was a young man.

Dr. D’Amours also shared her experience of bias in higher education. “I’ve participated in a number of major hiring decisions in the last few years, and it’s fascinating how recommendation letters are written. C.V.s cross our desks from men and women who have all tackled impressive projects, but they’re described in gendered stereotypes. Women tend to be described with words like motivational, collaborator, kind, communications expert.” Conversely, men tend to be described as strategic, competent, and decisive, clearly telegraphing their natural leadership skills.

Our interviewees noted that this discrepancy implies that women are appreciated for their interpersonal skills but are not perceived as decisive or strategic leaders. This viewpoint reinforces prejudices that weigh heavily on selection committees’ perceptions and choices and hamper women’s ability to break into leadership positions.

Big steps toward cultural change

Despite facing myriad challenges and obstacles during their professional careers, our interviewees were adamant that considerable progress has been made for women in leadership. Dr. Laflamme said she’s seen the effects of this progress. “The younger generations are introducing new mores and pushing for a cultural change. Buoyed by the efforts of the women who came before them — including ours — they feel more strongly about gender equity in academia.” She noted that gaps have been narrowing since the start of her career. Our interviewees identified two major cultural shifts resulting in more women in leadership roles.

“When a woman leads a university, that changes things in and of itself,” said Dr. D’Amours. “We represent women’s progress. Just us being here communicates a great deal without us having to say a word.”

The first is the influx of women into universities. There are far more women now than when our interviewees were doctoral students or new professors. Dr. Bouffard raised her own university as an exemplar of this transformation. “The situation is very different today. Universities have seen significant changes, especially Saint-Boniface. Women were only invited to study at Université de Saint-Boniface in 1959. Today, 67 per cent of our students identify themselves as women, and our leadership team is 61 per cent female. It’s a notable example of gender parity!” Our interviewees noted that more and more women can likewise be found in leadership positions outside higher education. Seeing more women in politics, for example, contributes to the normalization of women in leadership positions and helps propel women into these roles.

Evolving family responsibilities has also had an impact. Women in leadership positions are more supported at home, enabling them to balance work and family obligations more effectively. Men now play a more active role as parents, said Dr. Laberge, which helps redistribute parental labour, as does the normalization of paternity and parental leave. “Women have historically been the ones to interrupt their careers to care for their children. Meanwhile, men have been free to build their careers. The situation has evolved with the introduction of parental leave. Familial responsibilities are more evenly distributed within couples. This is a critical change allowing more women to take on leadership roles.” This shift in mindset and family structure has allowed for domestic responsibilities to be more equally distributed, which in turn allows women to take on high level jobs.

Toward gender equity in university administrations

Our panel ended the interview with concrete advice for working toward gender equity in university administrations. They highlighted the importance of demystifying leadership roles to encourage women’s participation by making roles more visible, clarifying administration’s responsibilities, and engaging women early in their university career — especially doctoral and postdoctoral students. They highlighted that the composition of selection committees is integral to equitable representation.

Our interviewees also offered practical tips for any new professors aspiring to leadership positions. Their main advice? Grow your self-confidence. Dr. Laflamme noted that “believing in yourself” is critical. “We often feel uncertain: Do I have the necessary skills? Will I be good enough? Am I self-assured enough?” Her advice is to push through, even if you don’t feel absolutely ready.

Dr. D’Amours agrees. “I always tell myself: Don’t self-reject.” She says it’s sad watching women talk themselves out of applying because they don’t think they’ll be selected. She encourages women to take a shot, as each application process is a great way to grow and build experience, whether or not they succeed.

“We often feel uncertain: Do I have the necessary skills? Will I be good enough? Am I self-assured enough?”

Support is crucial to developing women’s confidence in leadership roles. One-on-one meetings help encourage professors to consider administrative positions. “Everyone has to start somewhere,” said Dr. Bouffard. When professors express interest in administrative roles, she takes the time to sit down with them to discuss opportunities. Ms. Cohen recalled conversations with women who doubted their own skills because they lacked leadership experience, despite obvious potential. She often tells them, “You can do anything you set your mind to. Of course there is an institutional framework to deal with, but you decide how to lead based on your personality and priorities.”

Challenges remain, even as significant progress has been made toward gender equity. Implicit biases continue to affect how leadership roles are perceived within the academy and in the broader society. Dr. Laflamme says the obstacles to leadership are often “intangible.” Significant cultural changes are still needed for gender equity to become the norm, and Dr. Bouffard stresses that we must bring this cultural change about ourselves.

Upon sharing their examples of positive cultural change and concrete tips to help women obtain leadership positions, our interviewees wrapped things up on an optimistic note by underscoring their belief that gender equity in academia is not only possible, but essential.

When “a woman leads a university, that changes things in and of itself,” said Dr. D’Amours. “We represent women’s progress. Just us being here communicates a great deal without us having to say a word.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.