How education became a ‘promise of a future’ for Jesse Thistle

The York assistant professor and author of From the Ashes says he has a responsibility to those who suffer from addiction, and to his former self, to tell his story of homelessness and redemption.

One of Jesse Thistle’s most prized possessions is a plain piece of paper. After living on the streets, struggling with addiction and coming very close to death, in 2008 he was serving a year at Harvest House Ministries in Ottawa, instead of in a correctional facility, and learning how to take care of himself. That year in rehab included classes on communications skills and basic etiquette, overseen by Jenepher Lennox Terrion from the University of Ottawa.

By the time Mr. Thistle graduated from the etiquette classes, he had re-learned how to brush his teeth, shave and look people in the eye when he talked to them, among other things. He received a certificate printed on office paper for his accomplishments, with his name on it next to the words “University of Ottawa.” Mr. Thistle still has that piece of paper today; it’s behind glass and well preserved.

“It means the world, it still means the world… because it represented the hope of university. That was the first time my name appeared on anything that said ‘university’,” Mr. Thistle says.

“I’ve seen old marriages where they used to tie a string on each other’s fingers and they couldn’t afford a ring. It was what the intention represented. And that’s what that [piece of paper] represents to me,” he adds. “That’s my string on my finger. That’s my promise of a future.”

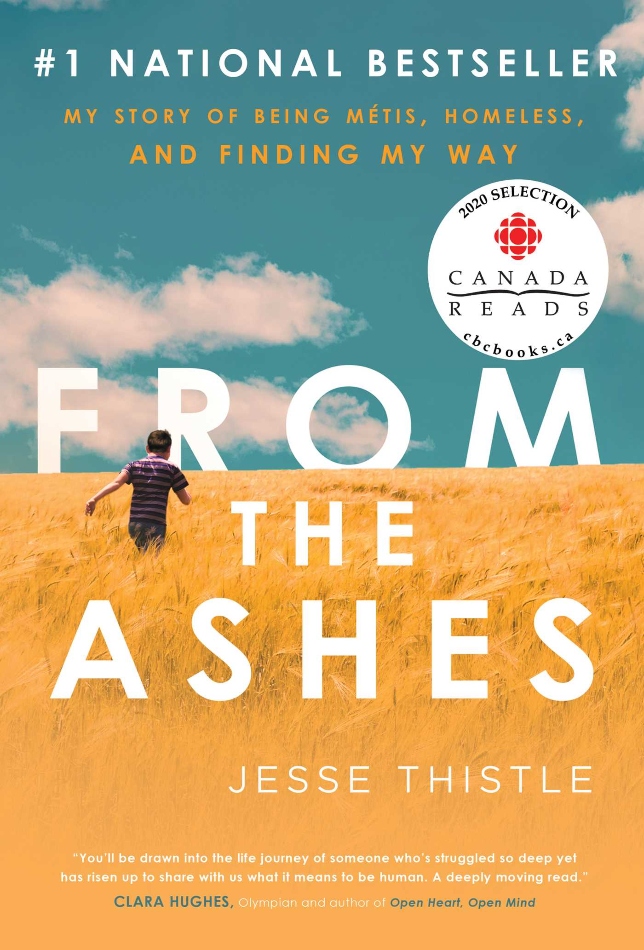

The etiquette classes and completing his GED at Harvest House were tangible steps towards Mr. Thistle’s academic dreams. He went on to complete a BA at York University and an MA at the University of Waterloo. Now, he’s a PhD candidate and an assistant professor in equity studies at York, a Trudeau and Vanier scholar, and an advocate for the homeless, having served as the national representative for Indigenous homelessness with the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. He is also becoming well-known in Canadian literature since his first book, From the Ashes: My Story of Being Métis, Homeless, and Finding My Way, became a fixture on bestseller lists after its publication last year. The memoir has won the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize Nonfiction and an Indigenous Voices Awards, and was named a book of the year by the Globe and Mail, CBC, and Indigo. And this week, Mr. Thistle’s title will compete against four others in Canada Reads, CBC’s popular “battle of the books” competition. While Mr. Thistle is pleased that Canada Reads has put a fresh spotlight on the book, he’s found the experience unsettling.

The Métis-Cree writer says he likely won’t watch the Canada Reads debates, which take place July 20-23. As the author of a piece of art about his own life, Mr. Thistle is reluctant to hear how the way he wrote about his traumatic and vulnerable experiences compares against the other books. “They’re going to be comparing my [memoir] to works of fiction. … I’m just telling my life,” he says.

The media attention has also been unsettling for the author. Although he has an education, teaches at a university and has a platform with people interested in what he has to say, Mr. Thistle says he is the same person who lived on the streets and still lives with trauma. “A lot of people want to know my name,” Mr. Thistle says of his life now. “But there was a time in my life where people literally walked over top of me and didn’t want to know my name. I tried to connect with them and tried to make them listen and they didn’t. And now they’re all listening.”

Born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Mr. Thistle spent his very early years living near his maternal grandparents. They were road allowance Métis, part of a little-known Métis population that was pushed off its North-West lands when immigrant farmers settled in the Prairies and ended up living on Crown land set aside for roads and highways. After his mother left and he and his two brothers were taken away from his drug-addicted father, they briefly lived in the foster care system before going to live with their tough-loving paternal grandparents in Brampton, Ontario. In From the Ashes, Mr. Thistle writes about how he then found himself in a self-destructive cycle of addiction and homelessness, struggling with the pain that he experienced first-hand but also the pain that he experienced through his family. Ultimately, it’s a depiction of how colonization creates and sustains trauma, passing it down through generations.

Writing a memoir wasn’t a goal he’d initially set out for himself and Mr. Thistle says it wasn’t a healing experience. As he told the CBC last fall, he had put some of his writing from rehab up on a blog, which led to a story about him in the Toronto Star. Simon & Schuster took notice and asked him to write the book. “I gotta get up on stage and disembowel myself every time I talk about this, and so there is no healing for me,” he says. “I have to remember the larger picture of why I published. … I was cognizant that my story’s representative of other people who suffered from addiction and homelessness, be they Indigenous or not. And I have a responsibility to them, and to myself, my former self on the streets, to tell that story.”

In From the Ashes, Mr. Thistle recalls his important first meeting with Carolyn Podruchny, a professor at York and an expert on Métis history. Dr. Podruchny hired him as a research assistant for a project that took them both to Saskatchewan, where he was able to reconnect with his history and his Métis kin. And much of his academic work since then has revolved around research on his family and the road allowance Métis in that province. With education’s historical legacy of harm against Indigenous people in Canada, reconnecting with his own history through academia was a subversive way to “re-Indigenize” himself, he says.

Despite the systems that led to Mr. Thistle being disconnected from his ancestry and to his challenges with addiction, he still holds onto hope that Canada can move in the right direction in its relationship with Indigenous peoples. In the grand scheme of things, he says, there have been significant changes within the last decade. “There’s more of an awareness around things like residential schools [and] Inuit relocations. Now the country’s just coming to the realization of things like road allowances and what happened in the Métis people after 1885, when our lands were stolen,” Mr. Thistle says. “But it’s taken a long time, and just as it took seven generations to get into the mess that we’re in, it’s going to take that long of telling the truth and then coming to terms with that truth and then making changes. So we’re just at the beginning of it all.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.