The long road to equity

Despite increased institutional commitment, experiences of men and women faculty differ starkly.

About six years ago, Amanda Moehring recalls a meeting where faculty had gathered to discuss student evaluations. To lead off, her male colleague overseeing the meeting began introductions around the table of mainly female participants, referring to each by their first name. When he reached the first male in the room, however, that colleague was introduced by his surname, preceded by the title “Dr.” All of the females in the room had doctorates, so the inconsistency was striking. As the meeting proceeded, she began referring to each of the women in the room by “Dr.” followed by their surname. In response, she remembers the male colleague chairing the meeting “stood there and sort of jerked back a little and looked flustered.” She says he then sputtered, “Oh, I didn’t mean, oh, oh… I didn’t realize I did that.”

“He genuinely didn’t realize what he was unconsciously doing,” says Dr. Moehring.

What Dr. Moehring witnessed in that room – females of equivalent educational status to the males being referred to, even if inadvertently, as if they had a lower rank – has a name: unconscious demotion. It refers to assuming someone holds a position of lower status or expertise than they actually do. This, explains Malinda Smith, University of Calgary’s associate vice-president of research (equity, diversity and inclusion), has been formally studied. It is just one of many types of unconscious or implicit biases that individually and cumulatively impact the composition of who attains faculty positions in academia, disadvantaging women, particularly racialized women, throughout all phases of their career, as outlined in her chapter “The Dirty Dozen,” in the 2017 book The Equity Myth.

Such biases, with impacts that begin before graduate school and continue on or off the tenure track and into leadership and administration, are variously labelled as unconscious, implicit, hidden, subtle, covert, invisible, or second-generation discrimination. A wealth of research suggests these biases function to limit entry and stall progress through the ranks, leading, in the case of gender and intersectional bias, to the term “leaky pipeline,” referring to the way in which scholars with aspirations for academic careers leave prematurely or are forced out.

Dr. Moehring, a Canada Research Chair in functional genomics and associate professor at Western University, considers herself senior enough in her career to have felt comfortable calling out the subtle bias she saw that day. It wasn’t the first incident she had experienced or witnessed. And hers is just one of myriad examples of gender biases that persist in Canadian academia today.

In 2025, where does Canadian academia stand on gender equity compared with the past? Has progress been made? And have programs designed to address gender bias and other inequities made a difference?

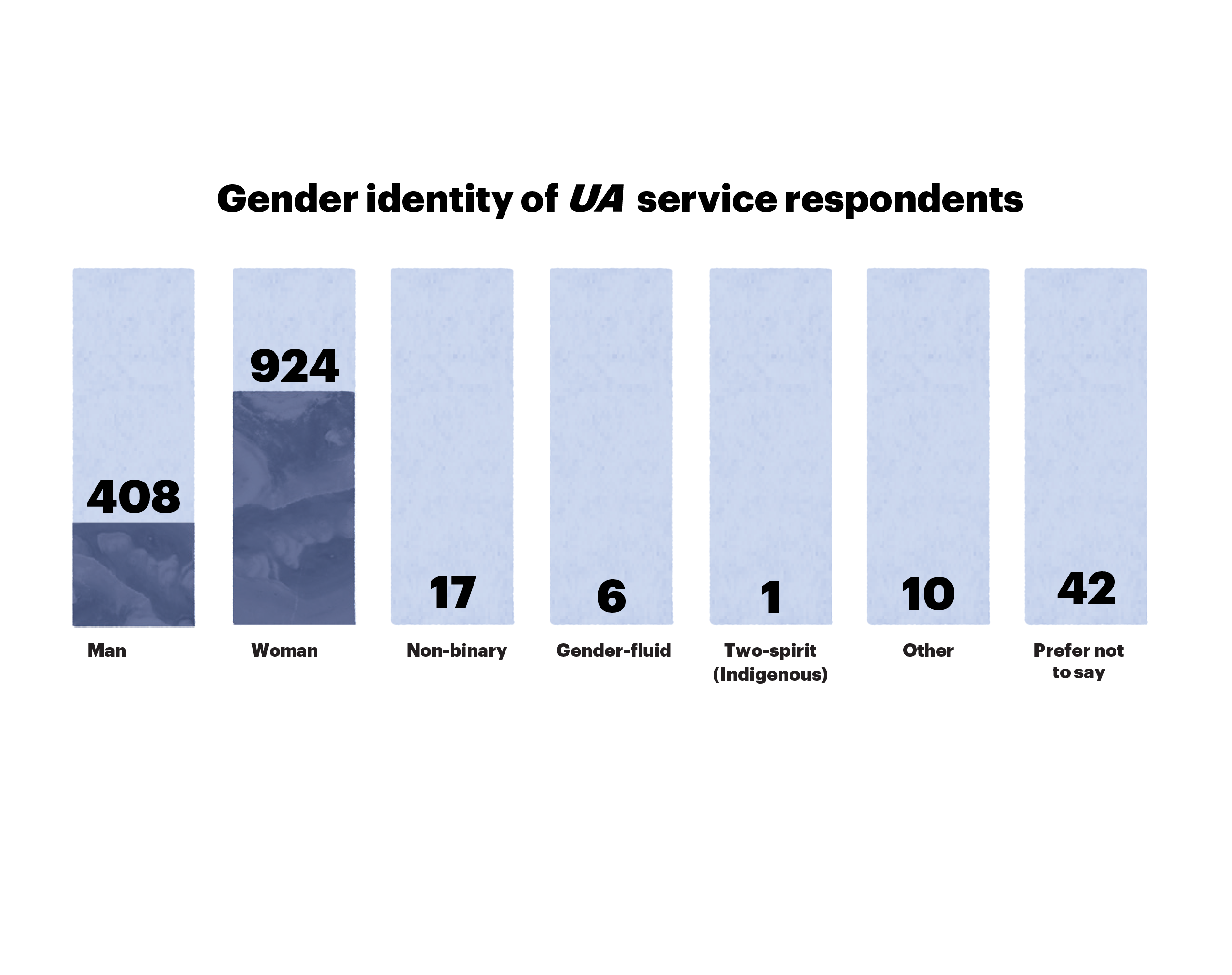

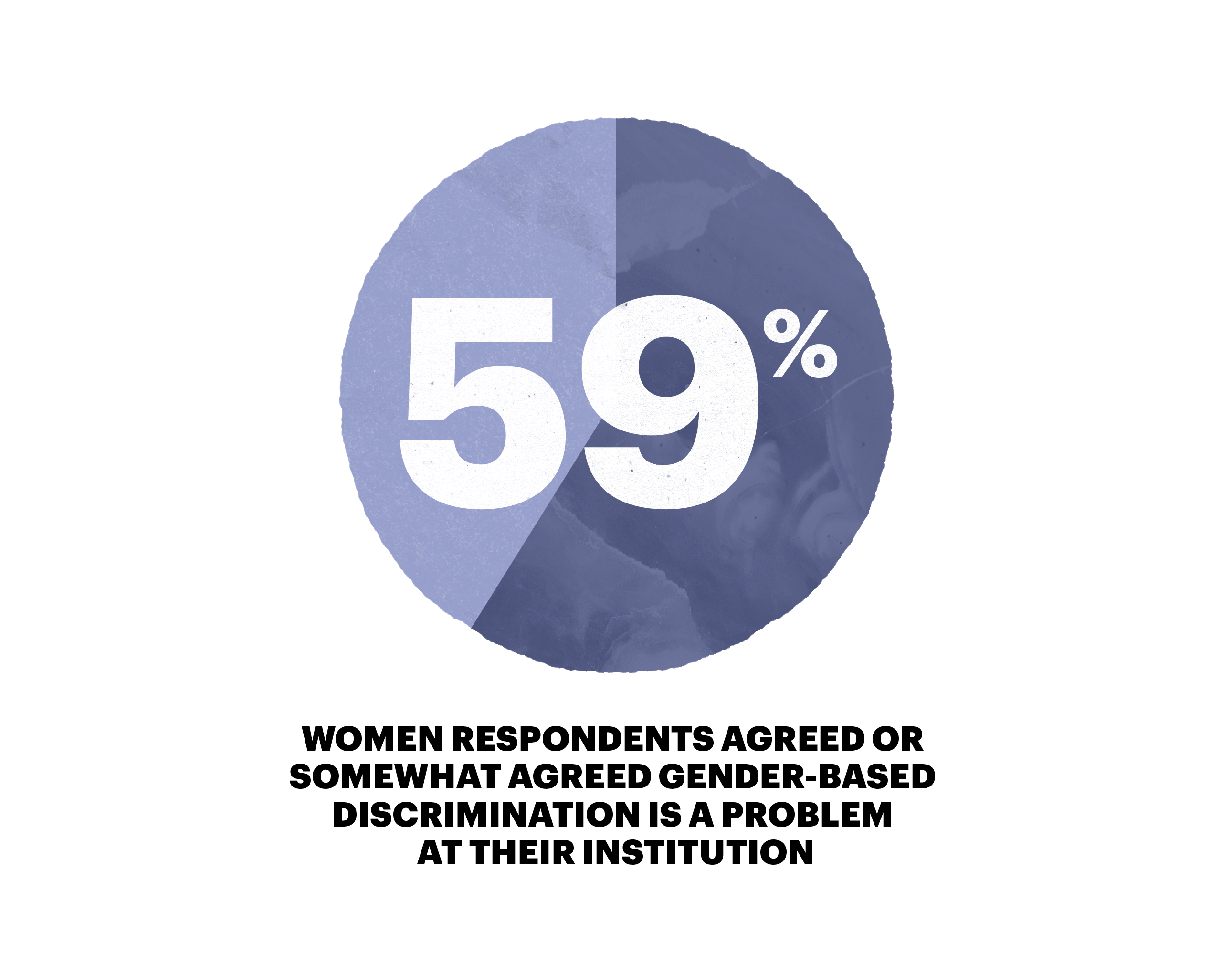

For this special issue, University Affairs commissioned a survey of academics at Canadian institutions, inviting all genders to participate, to find out. Data collected from the 1,408 faculty and administrative staff who responded to the survey suggest that progress is happening, but slowly. More than half of women surveyed agreed or somewhat agreed that gender-based discrimination is a problem at their institution.

Where We Came From

Taking us on a historical journey, Dr. Smith explains that Canada’s attention to the issue of employment equity traces back to the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, created in 1967 and tabled in the Canadian Parliament in 1970. That work focused attention on employment and hiring questions. Justice Rosalie Silberman Abella introduced the term “equity” in the 1984 Royal Commission on Equality in Employment.

The focus on gender inequity gained much greater traction with the Royal Commission. Beyond hiring, considerations included issues around care or so-called family-friendly policies and the gender wage gap or pay equity. “These are thorny issues. They’re not novel,” says Dr. Smith.

As for gender-based violence at Canadian academic institutions, that issue was brought to the forefront of public consciousness in 1989 with the massacre of 14 women at Montreal’s École Polytechnique, since renamed Polytechnique Montréal.

In 2017, the #MeToo movement focused awareness on gender-based violence, harassment, and discrimination more broadly. “It’s really important to frame these as not new issues,” Dr. Smith insists, but to frame them in terms of where we’ve come in the 40 years since the Abella report. “We see some progress, but it’s glacially slow.”

Where Are We Now

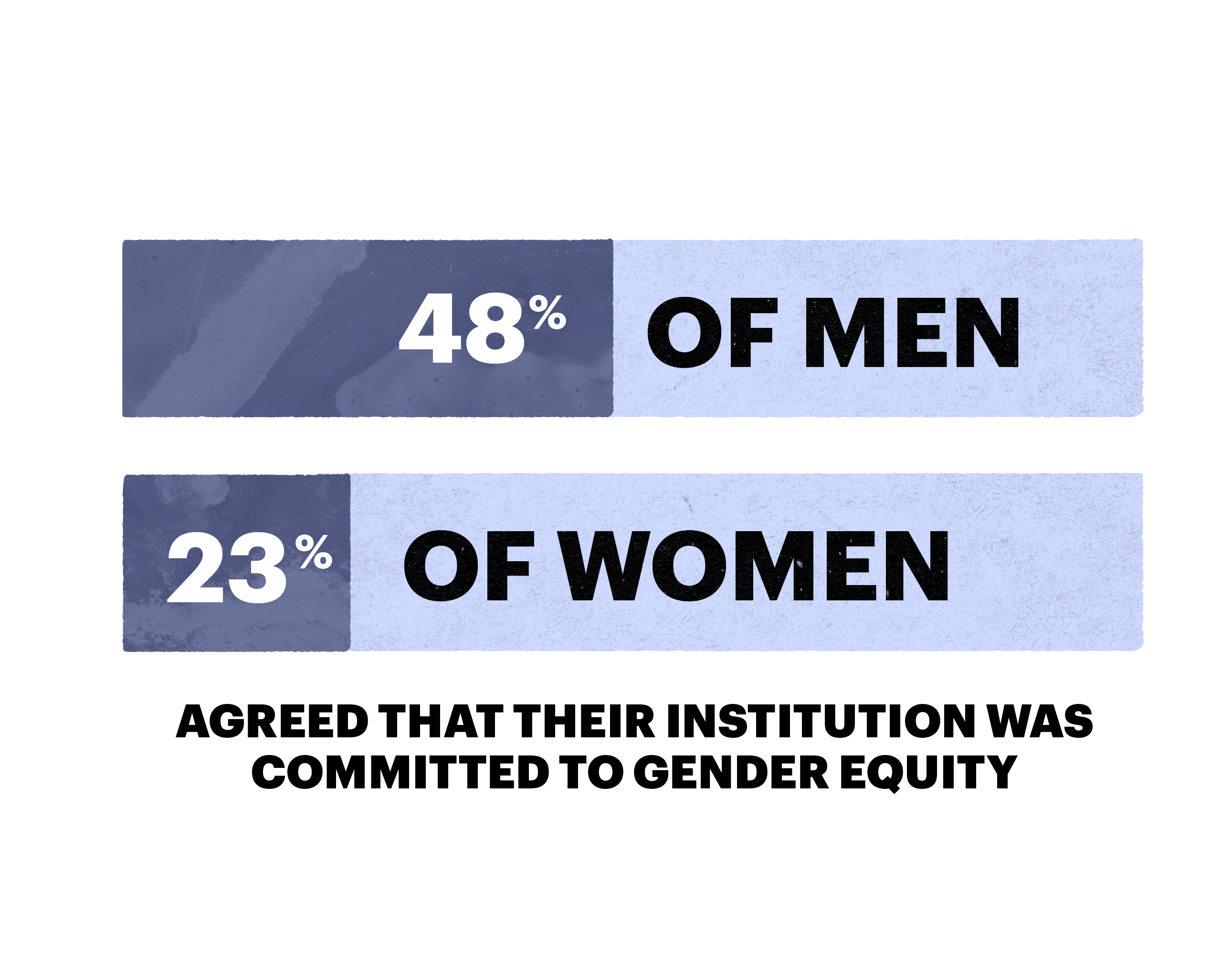

According to the University Affairs-administered survey, the extent to which individuals felt their institution was committed to gender equity was significantly different between respondents identifying as men versus women. Forty-eight percent of men agreed that their institution was committed to gender equity, compared to only 23 percent of women. Similarly, 11 percent of men and 24 percent of women agreed that gender-based discrimination was a problem at their institution, while 19 percent of women and 43 percent of men disagreed it was a problem – both differences statistically significant.

These findings are striking but perhaps not surprising. Research on gender bias shows that, at least in STEM fields, men and women are not equally receptive to experimental evidence demonstrating the existence of gender bias. A 2015 study by U.S. researchers, titled Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder, published in the journal PNAS, found a relative reluctance among men, especially those within STEM, to accept evidence of gender biases in their field. As that study’s authors outline, “This finding is problematic because broadening the participation of underrepresented people in STEM, including women, necessarily requires a widespread willingness (particularly by those in the majority) to acknowledge that bias exists before transformation is possible.”

The University Affairs survey data reveals differences in perceptions of commitment to equity by individuals with different genders and lived experiences in Canadian academia. The results speak to the difficulty of addressing discrimination that stems in part from biases that can be unconscious and unrecognized.

Pushing Forward

Maydianne Andrade’s involvement in equity-seeking work in academia began early in her career. “As a Black woman in academia, people have asked me to do this type of work since I started,” says Dr. Andrade, a professor of evolutionary biology and former Canada Research Chair in integrative behavioural ecology at the University of Toronto. She is also past president and co-founder of Canadian Black Scientists, as well as founder and co-chair of the Toronto Initiative for Diversity and Excellence.

Early on, Dr. Andrade says she was often the committee representative who “ticked a box,” but back then she said no to all explicit EDI-related queries because she felt she lacked the expertise. “As a scientist, just talking about my own experience was not something I was interested in.”

A Personal Turning Point

Around 2013, Dr. Andrade was challenged to take an implicit association test. “What I found was that I have a moderate to strong tendency to associate positive things with whiteness and negative things with Blackness. And that, of course, really shook me,” she says. This realization spurred her deep dive into the social science literature, where she recognized how poorly known this area of scholarship was among her colleagues.

Understanding bias, she says, “really does affect our ability to do our jobs well and to make good decisions.” Since then, Dr. Andrade has been deeply engaged in knowledge translation. A major pillar of the Canadian Black Scientist Network, she explains, involves interacting with parliamentarians and policymakers to stimulate sustained change.

Addressing Gender Discrimination

Dr. Andrade affirms that gender discrimination remains understudied in Canadian academia. However, she notes that data collection on gender equity at Canadian institutions is improving. Universities are required to collect employment equity data, and some institutions are making that data more publicly accessible. For example, she points to the University of Toronto and Queen’s University, both of which have dashboards tracking employment equity trends, such as the proportion of women at the assistant and associate professor levels.

That proportion, on average, “has been improving quite a bit across the Canadian academy,” she says, “although there are still big gaps in certain fields, like the sciences, relative to the proportion who are going into their undergrad and PhD programs.”

Nevertheless, when it comes to full professors, women remain underrepresented. “People say, well, you just need time for it to flow through,” Dr. Andrade notes. But the evidence suggests otherwise. If the proportion of women among associate professors a decade ago were translating into full professorships today, “we should see that proportion at the full professor level,” she explains. Yet the numbers don’t reflect that.

“We lose women between postdoc and faculty positions, and we lose women between associate professor and full professor,” she says. In the latter case, she clarifies that “losing” women doesn’t mean they leave academia entirely but that they often remain in the system without being promoted.

Women in Leadership

One positive trend, Dr. Andrade observes, is that more women are occupying leadership roles. “What that suggests is that universities have been looking for talent among women for leadership, because for leadership roles, you’re tapped by senior administration, whereas for full professor, your department is putting you up for full professor.”

However, when it comes to racialized faculty, she warns, “there is still a precipitous drop-off.” Intersectional data remains limited, making it difficult to track what’s happening to racialized women in particular. But data compiled from Statistics Canada and the Canadian Association of University Teachers, as analyzed in The Equity Myth by Dr. Smith and co-authors, suggests that racialized academics—including racialized women—are more likely to be in temporary, part-time, or precarious roles.

In a 2010 University Affairs article on racism in academia, Dr. Smith posed the question: “If I walk into the room and I’m the only person that looks like me, what kind of change can I believe in?” Fifteen years later, she says little has changed. “I’m still the only person [of colour] when I walk into a room of senior leaders, and I’m thinking of [all] Alberta universities, not just my own.” She adds that this pattern holds not only in Alberta but across Canada.

Sexual Harassment and Microaggressions

One of the survey questions asked how recently individuals had experienced or witnessed sexual harassment. More than a quarter of women respondents said they had personally experienced sexual harassment, and among those, 24 per cent within the last two years. In open-ended responses, participants also shared dozens of personal anecdotes about harassment they had witnessed or endured.

The most common forms of harassment cited were verbal harassment and unwanted advances. Respondents described experiences ranging from sexualized and inappropriate comments from faculty and students (e.g., “Oh my, you are hot”) to negative remarks about pregnancy and maternity leave during postdoctoral studies. Other incidents included stalking, intimidation, bullying, gaslighting, and unsafe work environments.

Not all responses were so alarming. One said, “Things are a lot better than they used to be. And I have been well supported and encouraged by other male professors and mentors, who have become long-lasting colleagues,” adding that “my department now is very inclusive and encouraging, which is wonderful to see!”

Ivy Bourgeault, a professor in the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa, notes that sexist microaggressions are something she has experienced throughout her career. “I’ve been asked in the context of interviews: ‘Are you married?’ ‘Do you have children?’ ‘Are you going to have any more children?’ That’s not appropriate,” she says. She remembers one job interview during which she was told, “Do you know that you are a very beautiful woman?”

When faced with these kinds of undermining biases and inappropriate advances, says Dr. Bourgeault, “You have to sit there and respond … because it’s a job interview, and you need the job, and you can’t look shrill.”

“It ends up being like someone’s farted in the room,” she adds, “because that kind of comment is not a compliment in the context of a job interview.”

Dr. Moehring recalls a similar moment early after being hired into her CRC position at Western about 15 years ago. A small group of colleagues was chatting at the pub on campus when a senior male colleague sitting at the table leaned over and said to her, “I could have gotten a CRC, but I’m not a woman.”

“I just froze,” she recalls. “I didn’t know what to say in response. And it was really offensive.” She later learned that at that time, CRCs were overwhelmingly given to men. “That story speaks to me of how somebody might feel entitled to say something dismissive … but also how they might have a completely wrong perception of the advantages they have had in academia.”

Dr. Bourgeault holds a Research Chair in Gender, Diversity, and the Professions. She notes that she feels very lucky to have landed her role at the U of O, a place she feels respected and safe, crediting that in part to a dean who is understanding of the experiences she has had, including changing institutions to avoid incidents of sexual harassment.

She points out that universities began as male-only institutions. Harvard College (an undergraduate college within Harvard University), for example, admitted only white men for more than 300 years. The University of Toronto welcomed male scholars beginning in 1843, but it wasn’t until over 40 years later that the first women were admitted. Academia was developed and constructed for white, middle-class men, very much from a colonial perspective, Dr. Bourgeault notes. That historical context casts a long shadow, and until it’s dismantled or changed, “that’s the structure that we all have to fit within.”

Reflecting on her own path, arriving at university after growing up on a farm, Dr. Bourgeault was inspired and excited to “make it” in academia.

“You then start to experience things that we now have a language for—microaggressions—little ways to undermine you based on your looks and your age and definitely your gender. And … do you or don’t you have kids, or when [are you] going to have kids? All of these little things accumulate and make it very clear that this [place] wasn’t made for you.”

It’s a familiar message for many of the women surveyed who said they continue to experience those subtle and not-so-subtle examples of gender-based discrimination. Notably, 28 percent of women respondents say gender-based biases have affected their promotions and access to resources, while 50 percent believe their gender has impacted their ability to secure funding or publications.

“People talk about it as a leaky pipeline, and that makes it sound like it’s gravity that’s pulling people out.” In fact, says Dr. Bourgeault, “women are actively pushed out of that pipeline,” partly by decisions that they make.

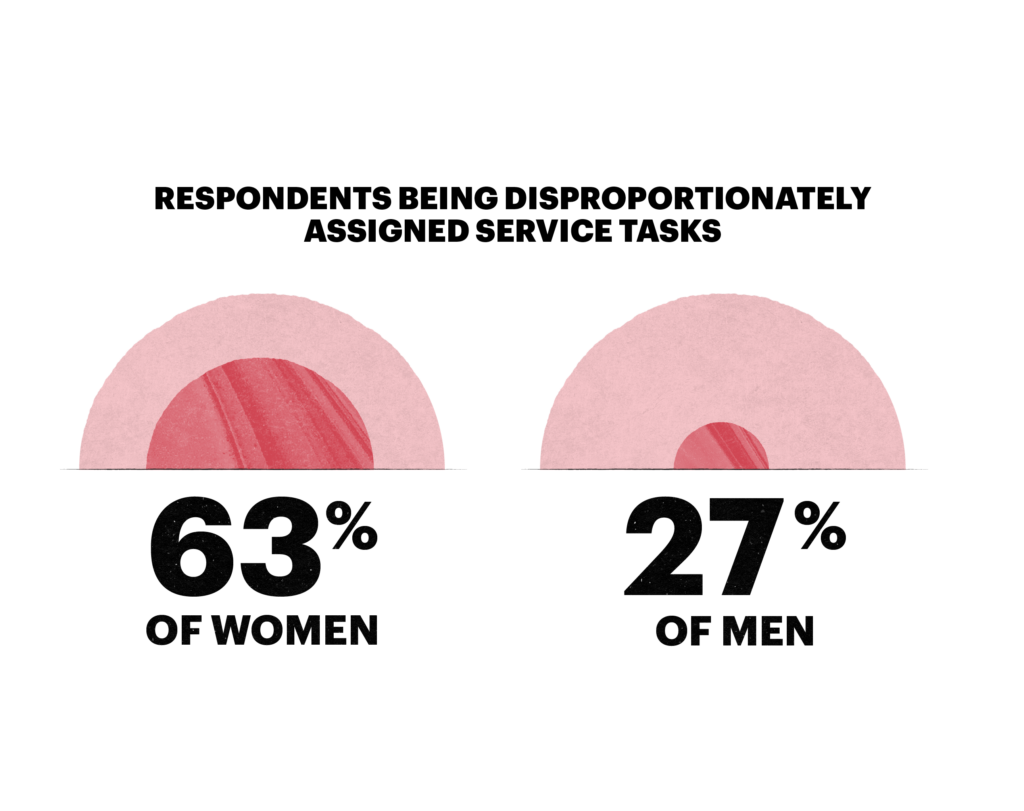

“If you have children, you’re on an off-ramp, and then you get put on the mommy track,” she continues, often with more teaching, serving on the undergraduate committee, and being disproportionately assigned something Dr. Smith calls the “housewifely work of the academy.”

According to the survey, 63 percent of women versus 27 percent of men responding felt they had been disproportionately assigned service work and administrative care activities compared with colleagues.

Hiring, tenure, promotion and leadership

To put a microscope on hiring equity, Lynn Arner, professor of English at Brock University, took a quantitative look at the situation in English departments in Canada. Drawing data from websites, she looked at where every faculty member who taught in an English PhD program in Canada earned their degrees, and their gender. “I found that women are more likely to teach in the contingent faculty pool, so outside the tenure stream.”

Some claim that women choose these roles to accommodate children, but that’s not what she found. “My respondents were reporting that they overwhelmingly wanted [or had wanted] tenure stream positions,” says Dr. Arner.

In examining scholarly and lay literature for her analysis, published in the paper “The problem with parity,” she also found an assumption that numerical balance is equity. “It’s not. I found that women have been getting the majority, by far, of PhDs in English on both sides of the border for decades.” That means that striving for 50:50 gender balance is over privileging men, she explains, “giving them an invisible affirmative action hiring program.”

Maja Krzic, a professor in the faculty of forestry at the University of British Columbia, worked with collaborators to assess gender equity in the field of soil science not just in Canada, but also in Egypt, Mexico, Nigeria, the U.K., and the U.S. Their 2025 study, led by Eric Brevik at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, compared data over time, from 1900 to 2024, and showed a slow closure of the gender gap at introductory levels. “Unfortunately, at mid-career or upper levels, the gap is still there,” says Dr. Krzic. One note of optimism was that compared with other countries, Canada has made progress, with nine female university presidents of its soil science society since 2005. “Even in Canada, our first female president was elected in 2005 and the society was established in 1955,” she notes.

Access to resources and mentorship opportunities

According to the UA survey, 17 per cent disagreed with the statement that men and women are given equal access to financial and non-financial resources. One survey respondent commented that, “Women systematically get deprioritized when it comes to research space allocation and the option to apply for CFI funding. It seems to be a bias, maybe because the negotiation differs from men during recruitment processes?” Another, identifying as a man, said, “Access to resources is a barrier for women with intersecting identities such as race.”

Another woman respondent said, “Males in our department get access to pre-established programs with lab space, technicians and mentors. New female faculty are expected to build our own programs and we are given lab space that we are expected to clean. Males can hit the ground running where barriers are in the way for females which either stall progress and result in non-tenure. It’s a huge problem where I’m at.”

And yet another recalled losing her lab space after giving birth. “The day I went into hospital to give birth to my son, the chair of my department gave my lab space away to another researcher despite my having technicians and grad students using the space. I was the first faculty member not to be given a departmental technician.”

Work-life balance

As for work-life balance, there was a strong signal from the survey. Of those sampled, men feel they have better work-family life balance than women academics.

Elaborating on what that looks like, one woman respondent said, “Men that are not the primary caregivers have the time and ability to research more, write more publications, apply for more grants, and then get said grants.”

Another woman noted that many assume it’s a level playing field, but it isn’t. “For example, the fact that women tend to have more responsibilities at home, such as for caregiving, and get behind relative to their male peers when they take maternity leave, is not considered relevant.”

Indeed, academia is seen by some as so hostile for work-life balance that a majority of women respondents said it has made them reconsider plans for family life based on their career.

Survey respondents also spoke to biases affecting tenure, promotion, flexibility for hybrid work, sponsorship, mentorship and how the pandemic had adversely affected their ability to meet teaching and research obligations.

“We lose women between postdoc and faculty positions, and we lose women between associate professor and full professor.”

Pay Gaps

An interesting feature of academic life in Canada, notes U of T evolutionary ecologist Megan Frederickson, is that faculty salaries are often publicly available information. In Ontario, all public sector salaries for employees who earn more than $100,000 are disclosed on a “Sunshine List.”

Realizing the availability of data, and as part of informal discussions in her department over the gender pay gap, she combined pay data with information from NSERC Discovery Grants, reasoning that the latter provided a metric of success in this particular competition. “I thought it would be interesting to look at these two things together,” she says.

That’s because Statistics Canada figures at the time, in 2016-2017, showed that U of T paid male and female professors median salaries of $168,425 and $145,150, respectively, a difference of $23,275 a year, or 14 per cent. “Over a 30-year career, this could add up to nearly $700,000 in lost income, a number that keeps me up at night,” wrote Dr. Frederickson.

Using a computer program to infer gender from her dataset, she found that in 2016, among all professors on the Sunshine List, women were paid $9,921 less than men – even when granted the same amount of funding, something she considered a metric of merit. “In other words, the gender pay gap is not because men bring in larger operating grants and therefore merit larger salaries,” argues Dr. Frederickson, who wrote up her number crunching for The Conversation Canada.

Since then, some progress has been achieved in closing the gender pay gap at Canadian universities, she notes, but adds that “I would love to encourage universities to continue to do their own analyses and to look for ways to close those gaps when they exist.”

King’s University College professor Marcie Penner also studied not only the gender pay gap but the pension gap that results when pay disparities carry on over the course of an academic career and into retirement.

What she found was startling. Dr. Penner, a cognitive scientist, had been part of a feminist caucus of faculty and other employees and in raising the issue of pay inequities, received pushback during collective bargaining with their faculty association. A survey at King’s in 2018-19 had flagged that only 50 per cent of faculty thought that pay inequities were an issue. At that time, exactly 50 per cent of faculty were women. “I think that made us pretty angry, if I’m honest,” she says. The message was that if only women thought it was an issue, it wouldn’t be addressed.

So Dr. Penner teamed up with her colleague Tracy Smith-Carrier to write a policy brief for her institution. A quantitative researcher, Dr. Penner wanted to quantify the numbers. “We ourselves were struck,” she says. The disparity was half a million dollars. By quantifying the lost income, the team was then able to get salary corrections for women and other faculty with salary anomalies.

Addressing gender biases and inequities

Dr. Penner has been encouraged by many faculty associations reaching out to say they used similar analyses to get salary anomaly information and corrections. She also testified last fall, along with Drs. Smith-Carrier, Andrade, Smith, Bourgeault and many others, at the House of Commons Standing Committee on Science and Technology hearings on closing the gender wage gap. The information from the study featured heavily in the final report and informed their recommendations.

“I am continuously encouraged by how much better things are now than they were 20 or 30 years ago. And I think a huge part of that is this feeling of public accountability that allows change to happen.”

However, when it comes to addressing gender and other biases, she says we are not systematically developing an evidence base to evaluate which solutions are effective and which are not. “It doesn’t mean that they [policies/programs] don’t work, but we don’t have evidence that they do work,” says Dr. Penner, who is at work on a systematic review of all existing research looking at ways to improve career outcomes of equity-denied faculty, not just women, but more broadly.

Cognitive neuroscientist Julia Kam at the University of Calgary, part of a team that summarized gender bias in academia and possible solutions in a 2021 paper titled “Gender bias in academia: a lifetime problem that needs solutions,” published by Neuron, says “We have come a long way,” again underlining the importance of considering the intersectionality of gender and other demographic characteristics, such as ethnicity and neurodiversity.

As a best practice, she advocates for bias training which can help to ameliorate discriminatory practices in peer review, hiring tenure, promotion and conference presentations. As one example, conference organizers can ensure an equitable balance of speakers and create a clear code of conduct with clear solutions in the case of harassment.

For her part, Dr. Moehring says, “I am continuously encouraged by how much better things are now than they were 20 or 30 years ago. And I think a huge part of that is this feeling of public accountability that allows change to happen.” She notes that when she was a graduate student, there were cases of sexual harassment; however, it was widely acknowledged that by coming forward, the only person that would suffer would be the victim. “That’s different now,” says Dr. Moehring. “There are still cases of that, to be sure, but it’s a very different feeling, with faculty at all ranks taking these things way more seriously and having accountability. I think that’s a massive change in the environment.”

As for her own personal experiences, she says the overwhelming majority of people she now interacts with are aware of microaggressions: “the death by 1,000 paper cuts – all the things that accumulate to make people feel unwelcome.”

“I’m not saying it’s 100 percent by any means,” says Dr. Moehring, noting there are still bad actors. “But I think the majority of people actually care about this and want it to be better.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

2 Comments

What if all hiring and promotion was merit based? Does DEI not discriminate against certain groups?

I applaud the efforts on this project, and it was an interesting read. I’m dismayed, however, at the suggestion that the problems might be fixed by more anti-bias training. The problem is systemic. A workshop on anti-bias will keep those DEI folks employed, but won’t help the problem. In fact, studies show the opposite, and they foster resentment.

What we need is for universities to commit to structural changes. Audit pay to determine if there is a pay imbalance. My own university committed to doing this, but has not followed through (I suspect they know they will have to raise women’s pay). Audit and ensure equity in service loads: put an hour value on the work in each role and ensure units are dividing those roles fairly. Stop using the student course evaluations for any tenure and promotion or merit pay purposes. Any promotion or merit pay decisions should be made by committee that is divided equally in gender, and where workloads are discussed and accounted for in those decisions. Again, at my school this is handled by the department chair alone, and this introduces clear opportunities for favouritism and bias.

What other demonstrable, actionable items could universities take? I’d like to hear the experts give us real answers, not more workshops that take up faculty time and do nothing to solve the issues.