Fighting fire with science

Powerful analytical tools and a new generation of wildfire specialists take to the woods as Canadian forests burn.

As a University of Toronto doctoral student working for Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) in 2020, Melanie Wheatley spent a summer analysing the efficiency of six different airplanes being used to douse Canada’s burning forests. Part of her research involved catching droplets from water bombers in 500 plastic cups that had been placed across an open field under the gaze of a tower-mounted infrared camera that measured the drop zone’s temperature fluctuation. It was part of a long-term study that is now influencing firefighting tactics.

Today, Dr. Wheatley works for MNR as a wildland fire scientist in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., where she continues her studies into the amount of aerial suppression required to reduce a wildfire. For example, her work can help predict how many water and fire-retardant bombings it will take to reduce an out-of-control treetop blaze, leaping ahead hundreds of metres at a time, into a manageable ground fire that surface crews can battle.

Combined with analysis from the fire danger rating system and other tools, her research helps provincial agencies plan the location and deployment of their fleets of water bombers, including Canadair CL-415s that can scoop 6,100-litre payloads from lakes several times an hour.

Across Canada, Dr. Wheatley and other university researchers are advancing the science of wildfire suppression as the world experiences devastating losses each wildfire season.

Record-breaking seasons

As of mid-July, there were 502 active fires in Canada with 150 of those listed as “out of control” by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre. The centre reported that forest fires have burned 4.6 million hectares to date this year, compared to about 923,00 hectares at the same time last year.

In 2023, the worst Canadian season on record, 6,623 individual wildfires destroyed more than 15 million hectares of Canadian forests — an area nine times the size of Prince Edward Island — and dislocated almost a quarter million residents.

Last year, there were only one-third the number of wildfires but few good news stories — much of Jasper, Alta., was destroyed in late July when 50-metre-high flames swept into the town from three local campgrounds. Six thousand hectares of surrounding parkland and one-third of the townsite were burned before the fire was brought under control.

Global climate change may be making the wildfire problem worse, but university departments across the country are stepping up their efforts to reduce the harm they inflict.

Rating the danger

David Martell, professor emeritus at University of Toronto’s Institute of Forestry and Conservation in the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, has spent almost 50 years studying the behaviour and patterns of wildfires. “People know how to fight fires,” he explains when asked about the role of academia in the field. “We provide knowledge, planning and decision-making (tools).”

As a graduate student in the 1970s, Dr. Martell helped fine-tune an early iteration of the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System, which has become a standard method of measuring the fire threat a region faces. “Fire danger” quantifies “the ease of ignition and difficulty of control” of a forest fire, and that information provides both a historical perspective of where fires are likely to occur and current data useful for assigning resources, from ground crews to aircraft.

Over the years, a weather index (to calculate the effects of wind, rain and heat) and a fire behaviour prediction system (to forecast the movement of a wildfire) have made the danger rating system more accurate, as provincial and federal teams calculate how fires will react to the presence of “fuels” (coniferous forest burns faster than mixed forest) and to specific topography.

Today, Mike Wotton, an adjunct professor at U of T’s Daniels Faculty and a senior research scientist at the Canadian ForestService (CFS), is contributing to a next-generation fire-danger rating system, last updated in 1992, with half a dozen other CFS scientists.

Among its refinements, the new system will provide better provincial and national forecasts of spring fire danger; fire movement beyond forest boundaries; the effects of forest thinning programs; and the threat of airborne fire brands/embers to spread flames across fuel breaks.

Planning locally

While wildfire fighting is usually managed provincially, the University of Alberta’s Jen Beverly, an associate professor in the Department of Renewable Resources, and U of A doctoral candidate Air Forbes have been bringing planning tools to front-line fire managers with a suite of sophisticated software tools that can be used at a local level, including by municipalities and isolated Indigenous communities, to plan wildfire defences.

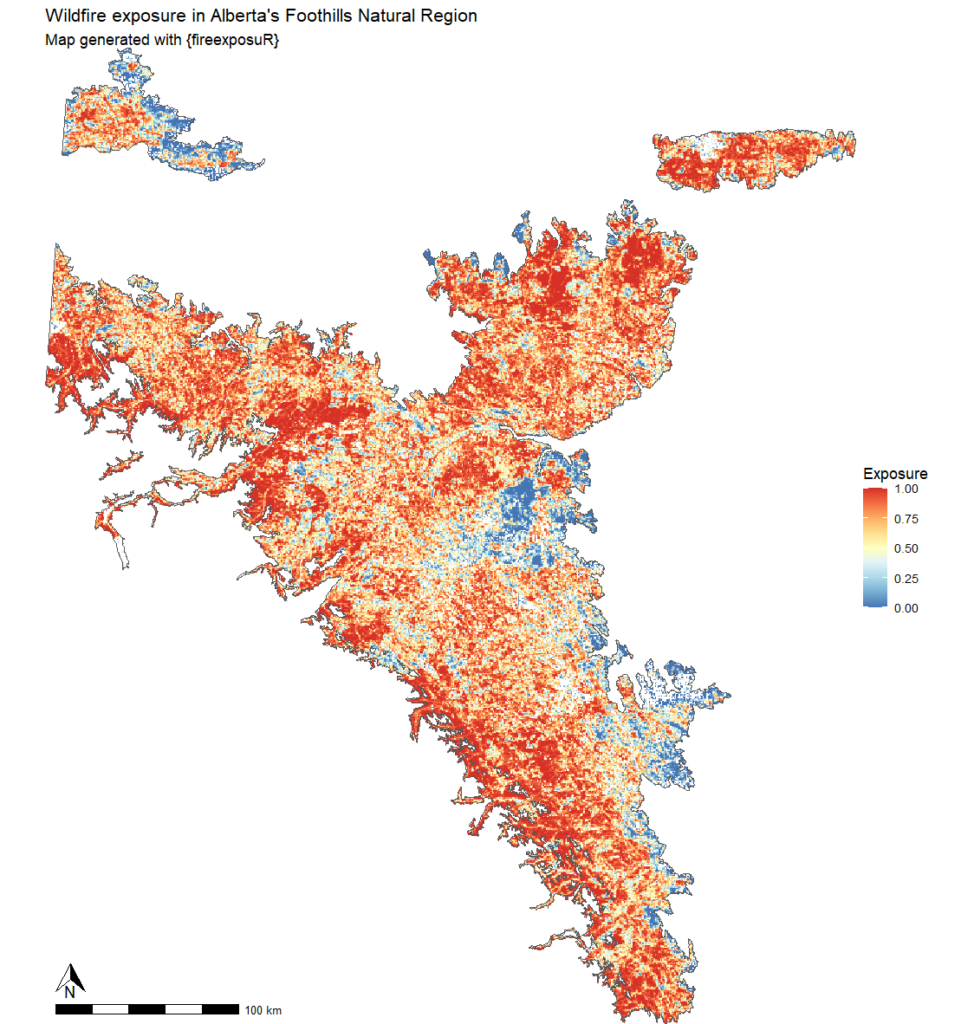

“We provide it for free or at little cost,” says Dr. Beverly of their open-source fireexposuR package. “The software is a simple, cheap tool that is quick, fast and easy to use.”

Based on the programming language R, the software allows managers to create meaningful maps that combine multiple data sets, such as local topographical information and fuel inventory reports, with weather predictions, maps of infrastructure, housing and evacuation routes.

Users, which now include several municipalities in Alberta and British Columbia, can use fireexposuR as a template upon which to add their own maps and relevant local information to get a custom statistical and spatial analysis without having to create their own software tools. So far, seven communities have used firexposuR to assess their exposure to wildfire, identifying neighbourhoods susceptible to airborne embers, for example.

“The program is a way to standardize community wildfire planning nationally,” Dr. Beverly adds. “To be effective, the system needs to be adaptable to local data, scales and goals. And this is easy to get, easy to learn and easy to use.”

Ms. Forbes has conducted free workshops for wildfire managers across Canada, in communities including Fredericton, Pikangikum First Nation in northwestern Ontario, Edmonton and Whitehorse, as word gets out about the power of the program she has developed.

Training firefighting specialists

Perhaps one of the most important resources that universities are adding to Canada’s wildfire fighting arsenal are experts — also called “highly qualified persons” — observes Dr. Martell. He has seen many of his graduate students go on to important work in the firefighting business, including Dr. Wotton, who spends much of his working life in Sault Ste. Marie at the CFS’s Great Lakes Forestry Centre. In turn, Dr. Wotton mentored Dr. Wheatley, the water bomber specialist.

Dr. Beverly was another of Dr. Martell’s students. Before assuming her professorship, she worked as a fire scientist for Natural Resources Canada, in private industry, and as a student on a variety of wildfire fighting crews, including as a “helitak” (helicopter attack) crew leader and fire ranger.

“Most of our graduates will work on air tanker bases, for Parks Canada or various provincial agencies,” she says.

Dr. Martell notes that placement of students into the wildfire field has become as important as academic publishing when applying for grants.

“When your students leave university, they bring their knowledge to their jobs and maintain their academic connections, initiating new research,” he declares. “It’s a strong collaborative relationship.”

Featured Jobs

- Soil Physics - Assistant ProfessorUniversity of Saskatchewan

- Canada Impact+ Research ChairInstitut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS)

- Engineering - Assistant Professor, Teaching-Focused (Surface and Underground Mining)Queen's University

- Anthropology of Infrastructures - Faculty PositionUniversité Laval

- Director of the McGill University Division of Orthopedic Surgery and Director of the Division of Orthopedic Surgery, McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) McGill University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

Dear Esteemed Researchers,

I would like to extend my heartfelt congratulations on your valuable and pioneering work in the field of fire information systems in Canada. In an era where disaster risks are growing globally, your scientific efforts are not only crucial for your own region but serve as a guiding light for communities around the world.

As an Assistant Professor at Necmettin Erbakan University in Konya, Turkey, I serve in the Civil Defense and Firefighting Program and conduct research focused on disaster management and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). From both a scientific and humanitarian perspective, I deeply believe that disasters like wildfires do not merely affect the regions in which they occur. They transcend borders—impacting our shared atmosphere, ecosystems, and economies—reminding us that geography has no real boundaries when it comes to disaster consequences. Like falling dominoes, the ripple effects eventually reach us all.

The interdisciplinary systems you are developing provide critical support in wildfire detection, response, and resilience-building. Your contributions are not only technically impressive but represent hope and progress in the global struggle against the increasing threat of wildfires.

I sincerely celebrate your dedication and success, and I wish you continued excellence in your future research.

Warm regards,

Dr. Hatice Canan Güngör

Necmettin Erbakan University

Department of Civil Defense and Firefighting

Konya, Türkiye