International student visa permits: What to know

IRCC announces 2026 international student targets.

After a steep rise in international student arrivals to Canada over the past decade, the federal government took unprecedented action beginning in 2024 to limit the number of student visa permits for international students to post-secondary institutions.

The announcement and subsequent measures have had serious consequences for the sector and universities’ bottom line. They have also caused confusion for post-secondary education stakeholders in Canada and damaged Canada’s reputation as a study destination abroad.

The latest policy changes following Budget 2025 have been hard to track – here’s a breakdown of what to know.:

The new cap – and what it means for the sector

On November 25, 2025, the government announced its international student targets for 2026.

Next year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) will issue a total of 408,000 study permits – this includes newly arriving international students as well as extensions. That is a 7 per cent reduction from the 2025 target of 437,000 and 16 per cent lower than the 2024 target of 485,000.

Of the 408,000 total permits, 155,000 will be given to new international student arrivals while the remaining 253,000 are expected to be for extensions for current and returning students.

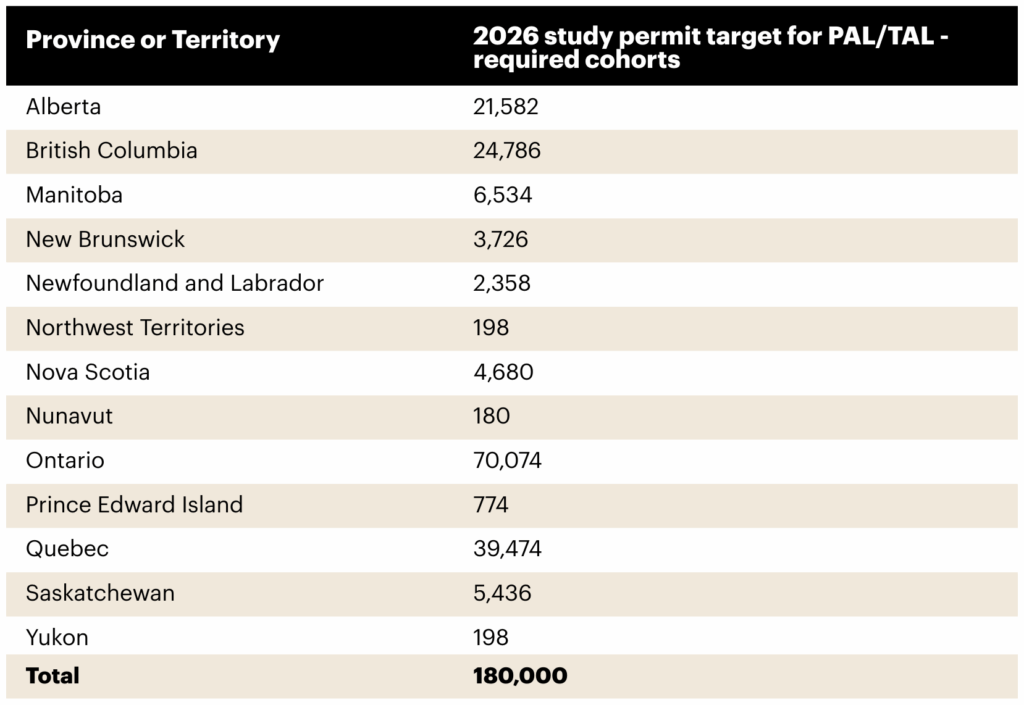

The number of study permits expected to be issued to students requiring a PAL/TAL in 2026 will be 180,000. This is distributed to each province and territory based on their respective populations. Here are the provincial and territorial allocations for 2026:

As of January 1, 2026, master’s and doctoral students enrolled at public designated learning institutions will not need to submit a provincial or territorial attestation letter with their study permit application, meaning they are exempt from the cap. However, they are included in the target of 408,000 issued study permits, which is being used to meet the government’s target for temporary residents in Canada. Within the 2026 national target, it’s expected that study permits issued to master’s and doctoral students at public institutions will be 49,000.

For 2027 and 2028, as announced in Budget 2025, the target for new arrivals will be 150,000.

The study permit issuance targets are aligned with the government’s goal of reducing Canada’s temporary resident population to 5 per cent of the total population by 2027, first announced in March 2024. According to IRCC, the international study permits cap has proven an effective tool: study permit holders dropped from over 1 million in January 2024 to about 725,000 by September 2025.

That year, the government had capped international study permit applications for 2025 at 437,000. However, not all students who apply for a permit end up studying in Canada, for a number of reasons. For example, international students who apply may not be accepted, or those who are accepted may choose a different country of study.

The discrepancy between the application ceiling and the actual number of international study permits issued is quite high. In 2024, applications were capped at 485,000, but only 293,220 new study permits were issued that year.

Many in the post-secondary sector believe that successive federal policy changes affecting study and work permits have tarnished Canada’s reputation as a study destination and caused uncertainty for prospective international students, leading to decreased enrolment.

New permits issued for 2025 are projected to be even lower. Sixty per cent fewer new students arrived between January and September 2025 compared to the same period in 2024 – down 150,220. While total applications are capped at 437,000, actual study permits issued in 2025 are expected to be around 120,000, with 80,000 for post-secondary only.

This suggests that there is some room to grow the number of international student applications from 2025 to 2026 in order to reach the 2026 target of 155,000. The new target is effectively more realistic for new international student arrivals following the disruptions to the sector from the 2024 announcement and is based on current PAL/TAL usage.

Graduate students, doctors and economic immigration

The federal government under Prime Minister Mark Carney is prioritizing both temporary and permanent residents that will fill specific labour needs and help to grow the economy – known as “economic immigration.”

The economic category will represent the largest proportion of permanent resident admissions each year, reaching 64 per cent in 2027 and 2028.

The government is also focusing on attracting graduate students who can support key sectors like emerging technologies, health care and skilled trades, who are seen as strong candidates for permanent residency.

On Nov. 6, 2025, IRCC launched a new website targeted at graduate and doctoral students to apply for study permits and visitor visas, work permits or study permits for family members. The process is streamlined and designed to identify clear pathways to permanent residency to keep recent graduates in Canada, according to the website. Doctoral students can have their study permit application processed in two weeks.

On Dec. 8, 2025, IRCC announced it would create a new Express Entry category for international doctors with one year of work experience in Canada within the last three years.

The government will also reserve 5,000 federal admission spaces for provinces and territories to nominate licensed doctors with job offers. Doctors can apply beginning in early 2026, and those accepted will have their permanent residence applications processed within 14 days.

The new measures for doctors, graduate students, doctoral students and their families are designed to support the government’s International Talent Attraction Strategy and Action Plan, announced in Budget 2025. The one-time initiative is aimed at recruiting highly qualified researchers to Canada for an accelerated international research Chair initiative.

The government plans to provide $1.7 billion over 13 years to the granting councils and the Canada Foundation for Innovation to recruit international researchers, doctoral students and post-doctoral students to relocate to Canada.

What other measures are in place?

Post-Graduation Work Permit (PGWP) program changes

The Post-Graduation Work Permit (PGWP) program allows students to continue working in Canada after they graduate. Access to work opportunities through the PGWP, and the potential for permanent residence based on that work experience, is one of the factors that appears to drive increased demand for studies in Canada, according to the government.

IRCC adapted the PGWP as follows:

- International students who begin a study program that is part of a curriculum licensing arrangement will no longer be eligible for a PGWP. Under curriculum licensing agreements, students physically attend a private college that has been licensed to deliver the curriculum of an associated public college. These programs have seen significant growth in recent years but have less oversight than public colleges, according to the government, and act as a “loophole with regards to post-graduation work permit eligibility.”

- Graduates of master’s degree programs are now eligible for a 3-year work permit. The previous criteria based the length of a postgrad work permit to the length of an individual’s program of study.

- Spouses of undergraduate or college graduate students are no longer eligible for open work permits – only spouses for graduates at the master’s or doctoral levels.

The cost-of-living requirement

IRCC has raised the cost-of-living requirement to align with the government’s “low-income cut-off” (LICOs) – an income threshold established yearly by Statistics Canada.

Prospective international students must prove they have enough money, without working in Canada, to pay for tuition fees, transportation to and from Canada, and living expenses for themselves and their family members, if they join them in Canada.

For those applying from September 1, 2025, one year of living expenses is $22,895.

Provincial and territorial attestation letters (PAL/TALs)

Post-secondary designated learning institutions have been required to confirm every letter of acceptance submitted by an applicant outside Canada directly with IRCC.

The government says the process enhances verification and protects prospective students from fraud, ensuring that study permits are issued based only on genuine letters of acceptance.

Most study permit applicants are currently required to submit a provincial or territorial attestation letter.

Primary and secondary students, Government of Canada priority groups and vulnerable cohorts, and existing study permit holders applying for an extension at the same designated learning institution and at the same level of study are exempt.

How did we get here?

Canada’s international student population has surged since the mid-2000s, dipping only briefly in 2020 during the pandemic. The record growth can be attributed to a combination of policy changes, demographic pressures, institutional incentives and global shifts in international student mobility.

In 2012, an Advisory Panel on Canada’s International Education Strategy identified international students as critical to addressing projected labour shortages, stating in its final report that its “specific goal is to double the number of quality international students within 10 years.”

By 2015, the total number of study permit holders across all levels of study reached 352,290, about double that of 2005. By 2023, the year before the caps were announced, it peaked at over one million, at 1,037,165.

Much of this growth occurred in public post-secondary institutions, where international enrolment more than doubled between 2011 and 2020. Their share of total enrolment jumped from 7 to 18 per cent as domestic numbers fell, likely due to population decline.

The surge coincided with declining provincial funding in several provinces. To compensate, institutions raised tuition and recruited more international students, whose undergraduate fees nearly doubled between 2011 and 2021 to more than $32,000 – often three to five times more than their domestic counterparts.

Ottawa doubled down in its 2019–2024 International Education Strategy, arguing that immigration would drive all net labour-force growth and positioning international students as ideal future permanent residents.

By 2022, international students’ economic footprint reached $37.3 billion in spending and supported 361,000 jobs — an increase of 195 per cent since 2014. At the same time, the rapid growth in both international students and other temporary residents began to expose strains and unintended consequences across housing, services and labour markets.

In January 2024, the federal government under then Immigration Minister Marc Miller introduced a series of reforms to Canada’s immigration system. The government said that while international students “contribute many social, cultural and economic benefits, rapid increases in the number of international students and a lack of provincial measures to temper this growth has threatened the integrity of the International Student Program, putting pressure on housing and support services and leaving students vulnerable to fraudulent actors and precarious situations.”

Former Minister Miller was particularly critical of certain private colleges that rely heavily on international students, calling some “bad actors” which he accused of exploiting the international student system by operating “under-resourced campuses,” lacking sufficient student supports, and charging high tuition while continuing to recruit and increase enrolment.

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

Would be interesting to know how this may impact on processing time for applicants (especially in light of apparent delays since the introduction of mandatory letter of acceptance (LOA) verification process etc), and also if the changes in the cap will impact on e.g. international students on short-term research visits/exchange etc.