The exploitation trap of hope labour

Non-tenured and precarious faculty deserve better.

Universities ought to be places that offer stable, secure and dignified employment to faculty and staff while encouraging all the members of our academic communities to flourish. Unfortunately, the Canadian postsecondary system depends on the incredible contributions of underpaid and undervalued contingent labourers. Canadian stats on contingent faculty are hard to come by, but as Samantha Stainburn said in her 2009 New York Times article, “In 1960, 75 percent of college instructors [in America] were full-time tenured or tenure track professors: today only 27 percent are. The rest are graduate students or adjunct and contingent faculty.”

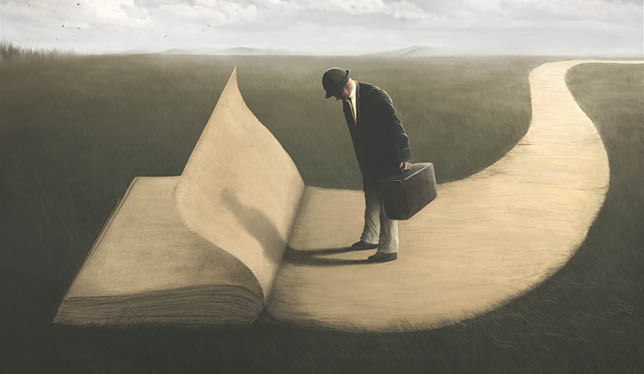

While some faculty appreciate the mobility offered by flexible employment contracts, many only stay in the academy in the hopes of landing a secure position as a professor or instructor with tenure or job permanence and meaningful employment benefits, like a pension and extended health insurance. As Keith Hoeller observed in Equality for Contingent Faculty: Overcoming the Two-Tier System, when students graduate with an MA or PhD, they are often deeply in debt, and those who are not lucky enough to land a tenure-track job must either accept a contingent position with few or no benefits or leave the academy. Those who take on contingent positions often stay in hopes that they will become more attractive to job search committees by putting in time and paying their dues as educators. This creates a system of exploitation, whereby some of the best and brightest minds in Canada get locked into the sessional trap by a cruel hope that, somehow, contingent labour will lead to stable employment within a vanishing permanent academic class.

As Judith M. Gappa and David W. Leslie note in their classic study The Invisible Faculty, departments are developing a bifurcated caste system, where precarious faculty “now carry a significant part of the responsibility for teaching, especially at the lower-division level of undergraduate education.” While full time and tenured faculty get to teach smaller, upper-level, boutique classes, many of those engaged as contingent labours are teaching lower-level classes with higher enrolments. As Frank Donoughue wrote in The Last Professors, most of the advice we give to precarious faculty is take-charge or involves self-help-based approaches that imply that one becomes or remains a sessional due to a lack of professionalization and job skills. In The Adjunct Underclass, Herb Childress says that we have largely given up on the idea that unlucky college faculty deserve to make a living wage. We expect skilled workers to be happy to be employed “course-by-course or year-by-year, with no guarantee of permanence, often for embarrassingly small stipends and no other benefits.” Yes, some faculty in these situations “write their way out,” to paraphrase Hamilton. I was one of them. I wrote academic articles and served on college and university committees while working as a contingent faculty member, and this helped me secure my first full-time job. My employer did not say that I had to do this, but the implication was that working as if I had a tenure-track job was the only way I would ever get one. The problem is that hundreds of academics do the same thing I did and do not land full-time jobs. They provide research and service labour that keeps their universities running and work for less than a living wage.

Those non-tenured and precarious faculty who work above and beyond their contracts are doing what Kathleen Kuehn and Thomas F. Corrigan call “hope labour.” Hope labour is a form of uncompensated or undercompensated labour carried out in the hopes that the exposure, experience, or goodwill generated by this labour will lead to future employment opportunities. Part of the issue is that teaching can be addictive. It is a rush to stand before a class, holding forth on an obscure topic you know well. It can feel like you are powerful, and all your training was worth it. The system relies on these positive feelings. It is hard to cut costs in a university, and the easiest way to keep budgets balanced is to keep faculty wages down. For those of us with more stable jobs and good benefits, sessional labour can become invisible, and thus we don’t see the human cost of maintaining the system.

I worry that, politically, this contingent labour crisis is invisible outside the university system, and that students and parents do not understand that many of the professors who are charged with teaching students are poorly paid, living contract to contract, and often working at multiple colleges and universities to make ends meet.

Hope labour is a trap. If you have hope that things can work out if you just teach one more class, publish one more article, or serve on one more committee, it can be hard to generate the momentum to leave the academy. Moreover, hope labour becomes a strangely effective way of maintaining a contingent labour force because it occasionally doles out rewards. We need stories of the hopeful, people who picked themselves up by their proverbial bootstraps, and who beat the odds. Their stories reinforce the idea that those of us who were lucky deserved our luck, and that there is a path to stable employment to be found through professionalization and hustle.

As academics, the kindest thing we can do for contingent workers is advocate for them whenever possible while, at the same time, helping them to get out of the trap that keeps them in exploitive working conditions. We need to reject the idea of contingent contract labour as a dignified way of existing within the university system, and we need to ensure that as many students as possible are taught by people who make enough money to stay out of debt, to have food security and stable housing, and maybe, just maybe, to take a nice vacation occasionally. The ideal solution to this problem would be massive worker demonstrations in the sector, a rise in the power of labour unions, and a return to 1970s levels of government funding for colleges and universities. Maybe it would involve boards of governors making massive cuts to the managerial and administrative class and redistributing that money to sessional employees. Faculty and unions should keep fighting for these radical solutions.

It shouldn’t be radical to imagine a university community where everyone is treated with dignity and respect, where all the employees are paid fairly, and where people have meaningful job security, employee benefits, and are paid a living wage. Hope is a beautiful thing, but we need to stop essentially paying people with hope and prestige. To do this, many professors and administrators who have the power to advocate for radical changes to the system need to see that the line that separates deserving winners from precarious employees is razor thin.

Featured Jobs

- Engineering - Assistant or Associate Professor (Robotics & AI)University of Alberta

- Chief Administrative OfficerUniversity of Toronto

- Medicine - Associate or Full Professor Professor (Kidney Health)Université de Montréal

- Sociology - Tenure-Track Position (Crime and Community)Brandon University

- Finance - Faculty PositionUniversity of Alberta

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.