Staying human in the Zoom boom

Video conferencing can be isolating and strange for some of your students – here are some tips to make sure everyone feels seen and heard.

In the past month I’ve reinvented myself as a Zoom host. I’ve leveraged 20 years as a facilitator, educator, and media producer with hours of experimentation and research that include facilitated meetings, family Skype gatherings, and guest teaching at my children’s homeschooling chaotic classroom meet-ups. In that time, I’ve learned a few things I’d like to share.

Overall, I find that Zooming with students can be a very positive experience — especially while we can’t be together in person. There are unique features, challenges, and delights in the Zoom world, and there is a skill set to make it a fulfilling, memorable, and transformative experience. Most of all, there is a lot of potential.

Beginnings and endings

When people first arrive on a Zoom call, we don’t know what they’ve been dealing with just before they logging-in. Since they are in their homes, the division between private and public has changed, and they have to transition into their public self in a matter of seconds. Helping to welcome them into the public gathering by simplifying any of the technical issues and facilitating low-pressure icebreakers can go a long way. When they are first joining, remind them to get a drink and to make themselves comfortable. In the “chat” function you can list some details about the gathering for when people first arrive, such as the format, what to do if they must leave the meeting early, or some standard practices for the gathering. Sharing a screen and showing a slide illustrating the basics of how to use Zoom can be helpful at the start for anyone who is still learning. It also allows people who are reluctant to participate verbally to still find their own way into the conversation or receive support.

How things end is also very important. Happiness research shows that we later determine if an experience was positive based on how it ended, in combination with any specific highlights. If a meeting runs long and the ending is rushed, there might not be a chance to say a proper goodbye, ask pending questions, or process feelings or concerns that came up. When meetings end, students will find themselves alone again. If we can make our endings more meaningful and thoughtful it can help our students greatly. A simple checklist can include:

- Allowing time to check-out and say good-bye. Ideally each person can speak, otherwise you can unmute everyone and all say a collective goodbye.

- Use the “chat” function to check-in about any lingering questions or concerns. Offer to remain after the meeting to talk with anyone.

- Invite people to write in the “chat” a brief note about what they plan to do after the meeting/event is over in order to help ground themselves and take care of themselves. This allows them to plan positive actions and to share ideas. It might help reduce the likelihood that once the meeting ends they will feel suddenly alone and directionless, unsure what to do and possibly just get sucked into social media instead of stretching, getting a drink, stepping outside, having a shower etc.

Being seen and heard

I always open online gatherings with an invitation to keep people’s cameras on. Sometimes people have asked for an extra minute to brush their hair or move their laundry. A non-judgmental invitation to share the space can include some reasons for why this is important or valuable. I explain that because many of us are isolated, seeing other human faces is a welcome reprieve from text, static images, and emojis — and less impersonal than a blank image. It can put people on the spot and feel like they are being overly scrutinized to share their video, and yet they often feel differently when they understand that seeing them or just their space helps us feel more connected and helps the speakers focus and not feel like they are talking to their computer screen but to people sharing space with them.

While it is best if people can all have their cameras on, there are instances when this can’t happen. Sometimes for technical reasons but other times it’s a personal preference or it might be particularly stressful for the individual, and so in those instances they can still be present through the chat. Having a facilitator read the comments aloud helps ensure the writers’ participation and inclusion when they may otherwise feel left out. I received feedback from one participant who was muted and had their screen off the entire time, they said that they had been crying and needed personal space but still wanted to participate. They reported that hearing the co-host read their comments from the chat made them feel included and grateful.

Icebreakers

Some possible icebreakers to use at the start of a meeting can include:

- Show and tell: Ask participants to select an object from the room to share. Invite them to hold it to camera and describe how it is meaningful to them or what it says about them. What’s interesting about this is that people often will remember the objects people shared. It provides an opening for further conversation and connection. It also allows them to be personal but to talk about something other than just themselves.

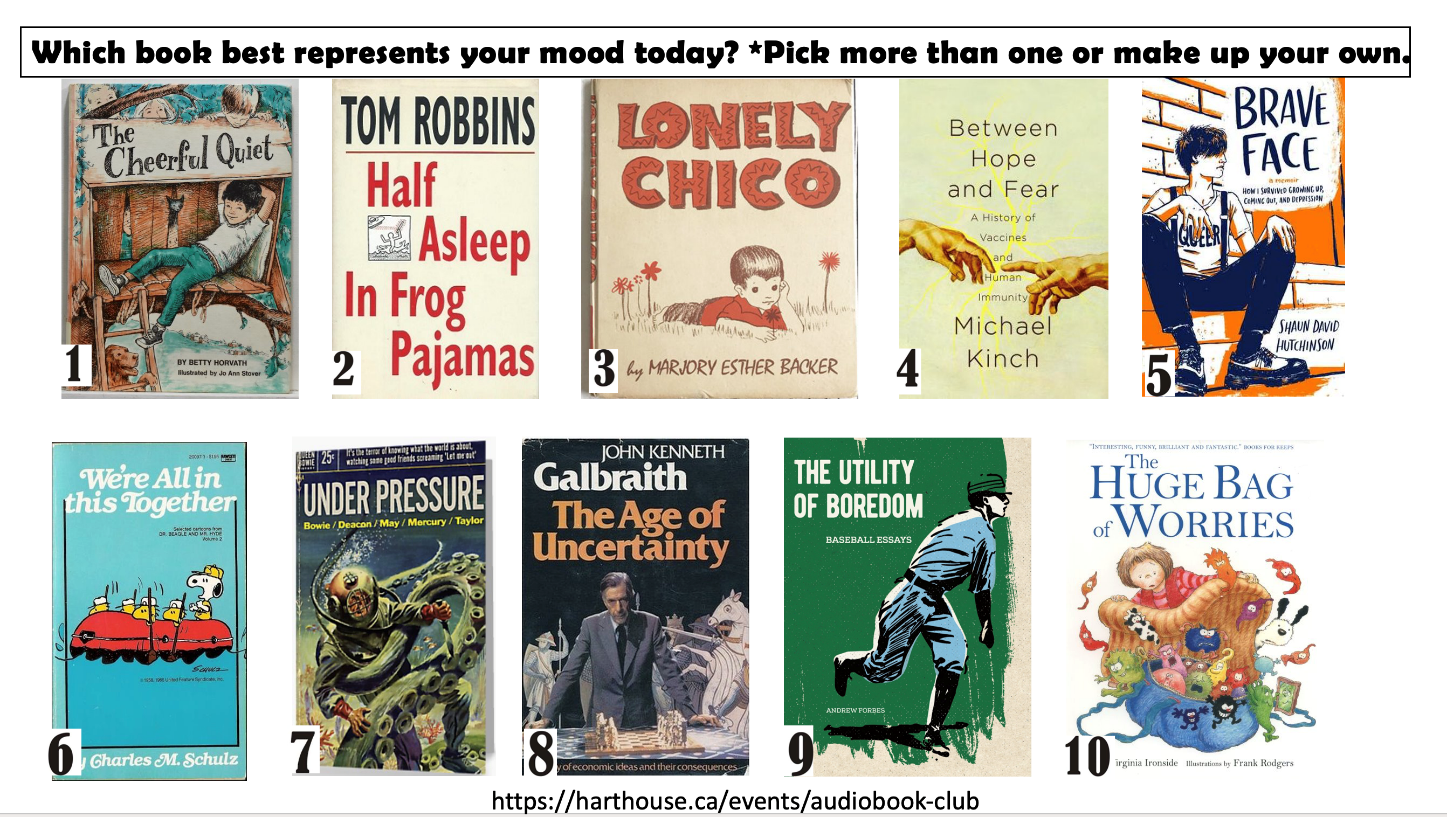

- Chose and share: The facilitator shares a slide with 8-10 images that could represent someone’s mood. Ask people to select which one or two images best describes their mood. This is a helpful activity because although it’s a bit abstract it allows them to be personal while providing an orienting prompt. It also allows participants to see commonalities they might have with each other. We created one for an audio book club showing 10 book covers; participants are asked which cover and title best represents their mood that day:

- What’s your emoji? Participants can enter an emoji into the chat and the facilitator(s) can acknowledge them and invite participants to explain why they chose the emoji they did.

- Using one word in the chat: Participants can be invited to write one word or sentence to describe what they are hoping to get out of the experience of participating in the event, and then everyone hits enter to share their comment at the same time. This is a great way to “take the temperature” of the room and can be done throughout an event to check in about where people are at.

Gathering feedback: using the “chat” function to complement the experience

It’s good to check in throughout the event for feedback through simple techniques like asking for nodding heads or thumbs up to show agreement or inviting people to enter one-word answers in the chat. You could ask: “Are we moving too slowly?” “Should we take a break?” without interrupting the flow of conversation. They can post to “Everyone”, or privately to the facilitator.

I find it’s very helpful to integrate the written chat function with the flow of the spoken conversation, and that they don’t interrupt or contradict, but rather complement, intensify, orient and help keep the conversation focused. It creates a layered way of communicating, just as we do in person with gestures and intonation. The chat function can be a “feeder” for the spoken conversation and allow everyone to take a break and reorient themselves based on what was written. It also allows you, as the leader, to use your own judgment to pick and choose selections that will direct the conversation in a helpful way. You can ask for feedback near the end of the session using the chat function. It’s important to remember to copy and paste the chat before ending the meeting to save the content for yourself or others, unless you have recorded the event in which case the chat will also be saved. I have asked questions like:

- “What was a highlight from today. What is something you liked or would want more of?”

- “What didn’t work for you? What would you like to change?”

- “Do you have any other suggestions or ideas to share?”

Last thoughts

- It’s best to facilitate in teams, so that one person can manage the chat and technical issues while the other takes the lead on facilitation. This allows for a more fulsome and less hurried engagement.

- Meetings longer than 1.5 hours should include a break.

- It helps to establish an order for speakers if you are going around for responses, so that people know when they’ll be called on and can prepare mentally and also unmute themselves. Similarly, during a discussion if you are going to call on someone for their contribution, start by naming them and then describing what you hope to hear from them, as this gives them time to get to their mute button and not feel frantic or hurried before speaking. For example: “Sasha, it would be great to hear from you about your experiences volunteering at the food co-op.”

Carly Stasko is an educator, journalist and coordinator at the University of Toronto’s Hart House, working with colleagues to support students and the broader community to stay connected during these times of physical distancing through common interests in the arts, dialogue, wellness and community engagement.

Featured Jobs

- Electrical and Computer Engineering - Assistant/Associate ProfessorWestern University

- Economics - Associate/Full Professor of TeachingThe University of British Columbia

- Electrical Engineering - Assistant Professor (Electromagnetic/Photonic Devices and Systems)Toronto Metropolitan University

- Fashion - Instructional Assistant/Associate Professor (Creative & Cultural Industries)Chapman University - Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences

- Indigenous Studies - Assistant Professor, 1-year termFirst Nations University of Canada

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.