A brief history of clock towers on Canadian university campuses

Now mostly admired for their aesthetics, university clock towers were originally erected to reinforce the concept of an orderly sense of learning and to help students get to class on time.

Mention clock towers and most people will think of Big Ben, the nickname for the elegant, chiming clock at the north end of London’s Palace of Westminster, or the clock on the Spasskaya Tower of Moscow’s Kremlin, a landmark so revered that many Russians once believed it possessed the power to protect the Kremlin from enemy invasion.

Although clock towers are still admired for their aesthetics, in a world where time is at everyone’s fingertips, their important original purpose has been largely forgotten. Before the 20th century, most people did not own watches and prior to the 18th century even home clocks were rare. The first tower clocks did not have faces, but were equipped solely with bells or chimes that were rung to call the community to work or to prayer. They were placed in towers so the bells would be audible for a long distance. As these towers became more common, their designers realized that adding a dial to the exterior would allow townsfolk to read the time whenever they desired.

Historically, clock towers also played a symbolic role as monuments of power and structure. Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe, professor emeritus in the department of art history, visual art and theory at the University of British Columbia, notes that clock towers on administrative buildings “expressed the dignity and authority of the local government. They were to assure everyone that things were moving forward in a measured and organized manner.” Similarly, on university campuses they were erected to reinforce the concept of an orderly sense of learning and to help students get to class on time. Here’s how a few notable clock towers came to be on Canadian university campuses.

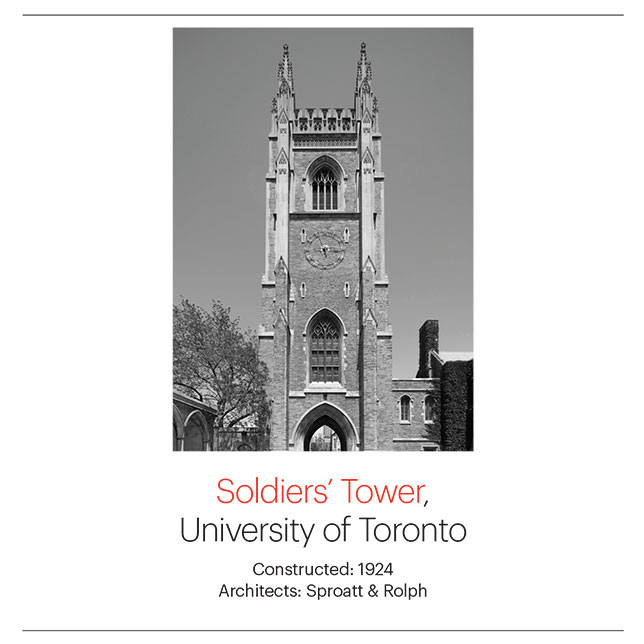

Soldiers’ Tower was built in 1924 with funds raised by the University of Toronto Alumni Association as a memorial to U of T students who died in the First World War, though it now commemorates all those from U of T who lost their lives in combat.

The Gothic monolith on U of T’s St. George campus is adorned with a beautiful stained glass window that features a 12-panel visual interpretation of John McCrae’s poem In Flanders Fields, and a memorial room with portraits of graduates, medals, flags, photos and a WW1 German machine gun.

The clock was purchased later, in 1927, from the British firm Gillett & Johnston, along with 23 carillon bells. A carillon is a musical instrument consisting of a set of bells cast in bronze and tuned so that a player on a keyboard can sound them. Today, the tower houses 51 bells ranging in weight from 10 to 3,600 kilograms. The only functioning carillon at a Canadian university, it plays during June and November convocations, informally for short intervals each week, and for formal, one-hour recitals.

The tower is said to harbour the ghost of a caretaker who was rumoured to have fallen to his death in the 1930s while polishing the bells. Students have reported seeing a shadowy figure falling from the tower.

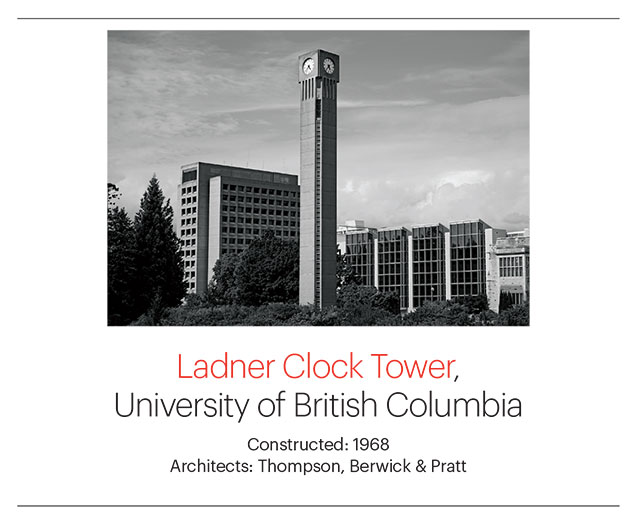

The UBC clock tower was a gift from Leon Ladner, a prominent Vancouver lawyer and ardent supporter of the university, who donated $150,000 for its construction in 1966. He intended it as a tribute to the province’s founding pioneers (including the Ladner family), but some students opposed the idea. Donald Gutstein, writing in the student newspaper The Ubyssey in 1967, called it “a functional, social and visual irrelevancy” and complained of “the monotonous and inconsequential tolling of the hours, hour after hour, day after day, year after year, century after century” that the clock would bring to the campus.

The original tower included a carillon composed of 330 small bronze bars that could be played by small metal hammers. In 1997, it was replaced by a digital system able to play a variety of synthesized bell sounds. The clock is controlled by a master mechanism housed in the equipment building beside it.

Music broadcast from the tower has become a traditional part of school ceremonies, but students have never treated the landmark with much reverence. The Ubyssey has depicted it draped with a condom, and in 2014, UBC engineers pulled off a prank that resulted in a red Volkswagen Beetle miraculously appearing atop the concrete spire.

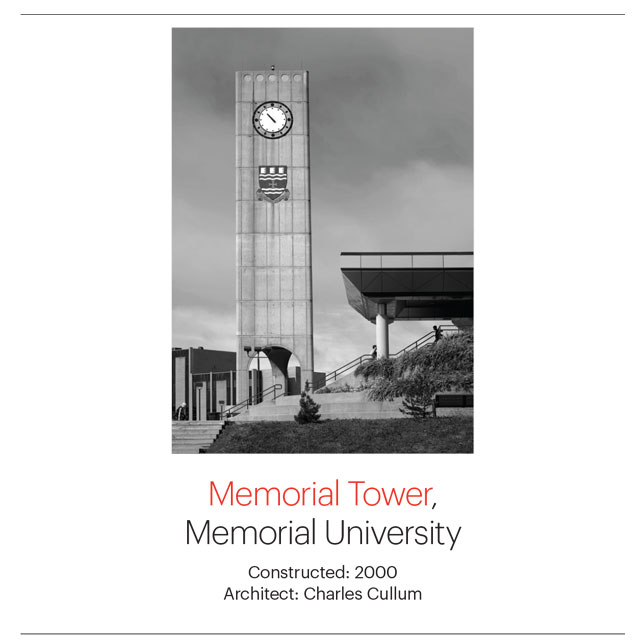

Much like Memorial University itself, the Memorial Tower was established to honour Newfoundland soldiers who fought in the First World War. The Johnson Family Foundation, which supports the preservation of heritage sites in the province and other charitable endeavours, paid $500,000 to erect the tower, which now provides a central visual landmark for the university campus.

The tower entails several curiosities. Although the cement behemoth does feature a large plaque honouring fallen soldiers, it’s hidden away on the structure’s least visible side, facing a concrete wall. Student lore contends that it was never actually finished. Some say there was to be a dome, a spire and even an “eternal flame” capping the triangular tower.

Certainly, the builders failed to take into account St. John’s breezy weather. A storm blew the clock hands off kilter soon after it was installed and, for a while, the tower’s three clock faces told different times. In 2016, the clock was overhauled and had a new cast acrylic face installed by the Verdin Company, which claims more than 55,000 installations worldwide, including the clock faces at St. John’s Basilica and Ottawa’s Peace Tower.

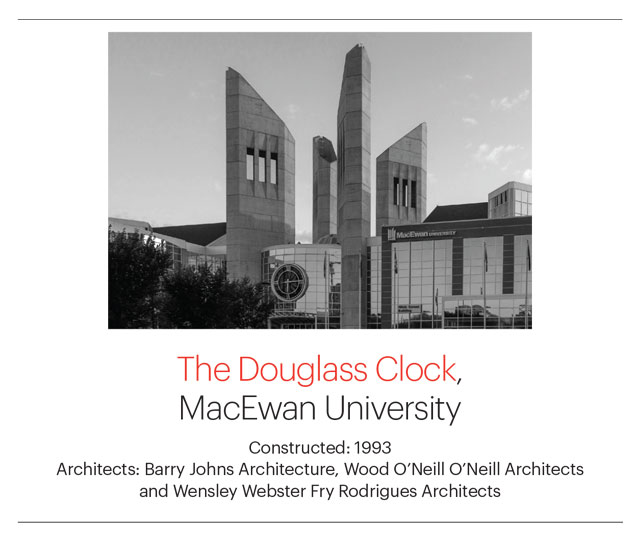

The postmodern clock tower at MacEwan University doesn’t conform to traditional expectations. Instead of having clock faces affixed to a single tower, this massive circular timepiece is actually a clock surrounded by towers – four jagged concrete spires that are repeated as a design motif throughout the university’s City Centre campus, which extends for six city blocks along Edmonton’s 104th Avenue.

The “Oxbridge” model of Gothic architecture influenced the campus layout, but the clock itself seems to draw from the glittery metallic fashion excesses of the 1990s. Its huge aluminum face only sports four numerals, 3, 6, 9 and 12, and is surrounded by reflecting glass.

Called the Douglass Clock, in recognition of Eric and Helena Douglass’s contributions to Grant MacEwan Community College (the university’s predecessor), it draws attention to the campus main entrance, which otherwise would not be easily distinguishable. “It’s iconographically powerful,” says Barry Johns, one of the architects responsible for the campus design. “It’s become a city landmark. Everybody knows it.”

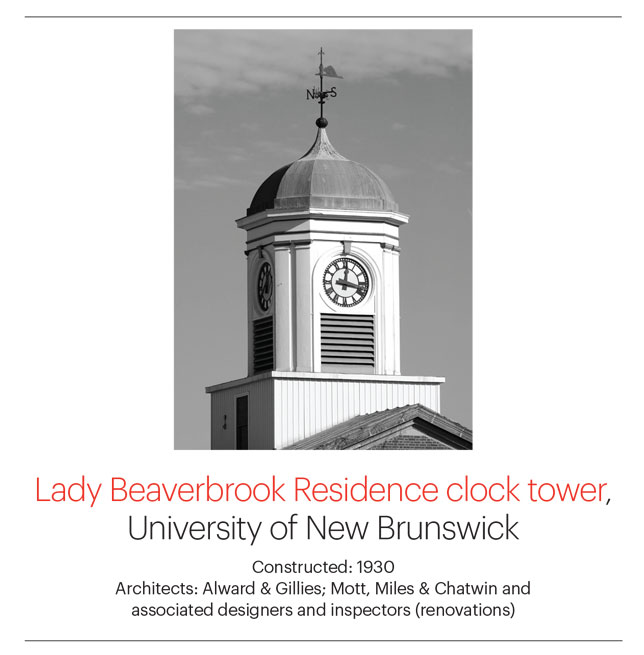

This four-sided clock tower crowns Lady Beaverbook Residence, which was an all-male residence until 1984. (Female guests were only allowed in residence bedrooms for 30 minutes during formal dances, and both feet of the occupants had to remain on the floor with the door open at all times.)

The building was constructed on UNB’s Fredericton campus by Lord Beaverbrook – also known as Sir Max Aitken, Canadian financier and newspaper publisher – in honour of his first wife, Gladys. It was intended as an exclusive residence, cloaked in decorum and dignity, with spacious lounges and a giant dining hall. Flourishes of that feeling remain with its brick detail, carved stone entrances, mansard roof, ivy-covered walls and clock tower, which is capped by a beaver weathervane.

The tower’s chimes, which once signaled the start and end of class lectures, play “The Jones Boys,” a Miramichi folk song favoured by Lord Beaverbrook. The bells fell into disuse over time but were revived in 1995 by a donation from the class of 1947 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of their graduation.

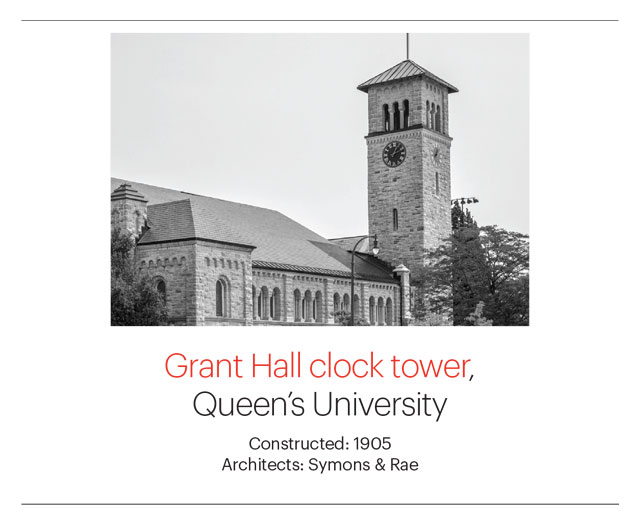

Installed in 1905, this limestone clock tower is the university’s best-known landmark. It sits atop Grant Hall, a 900-seat auditorium used for public lectures, concerts, convocation ceremonies, dances and exams. Named after George Monro Grant, principal of Queen’s from 1877 until his death in 1902, the building served as a military hospital during the First World War. In the Second World War it became a meal hall and entertainment centre for troops.

Nathan Dupuis (1836-1917), a professor of mathematics and dean of applied science at Queen’s, not only invented numerous pieces of scientific and practical instruments for the university, but also designed the original clock.

Over the years, the clock had trouble keeping accurate time and its hands eventually became frozen in place. In 1993, the clock was replaced with an English-designed electrical mechanism. Students paid for the device, continuing a tradition of directly supporting Grant Hall, which was constructed with $30,000 raised by students. Unfortunately, the new clock has also malfunctioned. In 2006, it was renovated yet again.

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

2 Comments

There’s also the bell tower (with clock) at Massey College, designed by Ron Thom, in the University of Toronto, which is worth mentioning in terms of its modernist architecture.

There is also a clock at McGill Unversity – recently restored by my firm, additional information at the link below;

https://www.electrictime.com/news/mcgill-university-clock-restoration-unveiling/