Pioneering biologist Anne Innis Dagg gets her due

Canada’s “queen of giraffes” – denied tenure because she was a woman, despite her groundbreaking research – finally gets the recognition she deserves.

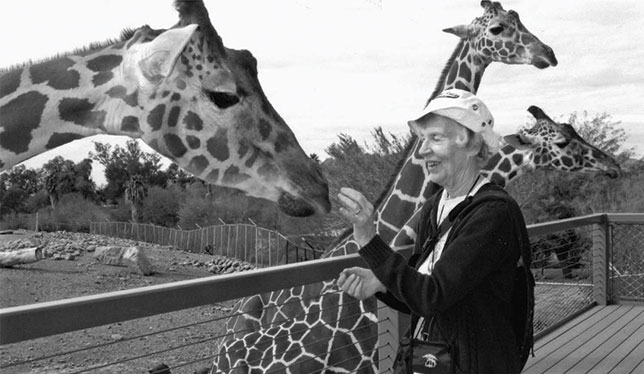

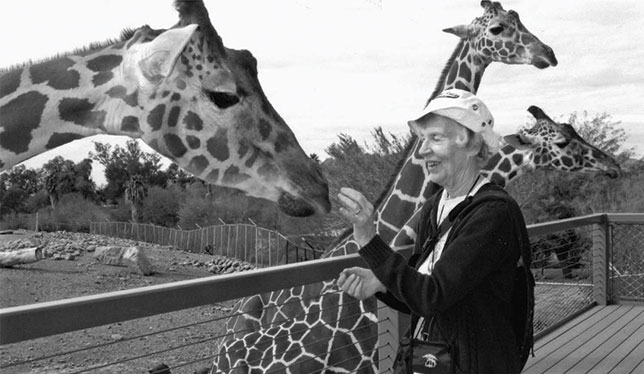

After a screening of the documentary The Woman Who Loves Giraffes this spring in Toronto, the audience rises, tears in their eyes. They leap up again when its subject, Anne Innis Dagg, takes the stage wearing a large smile and a yellow shirt with giraffes on it. There’s another standing ovation in the Q&A session after, when a student of Dr. Dagg’s from 1965 takes the mic. “It is evident that you have shown the strongest leadership over the last 54 years in science, but in particular in personhood. And I applaud you and I ask you all to stand for this fine woman.”

After, at the back of the theatre, Dr. Dagg, 86, draws a crowd. “She’s a rock star now,” says the film’s director, Alison Reid. At screenings across North America that both have attended, people flock to Dr. Dagg. “It’s really nice to see her get the kind of recognition and accolades that she so richly deserves.”

Indeed, for vast swaths of Dr. Dagg’s career, she got few kudos. She visited South Africa in 1956, in the early days of apartheid, to observe giraffes. She went alone and without a university’s financial backing or other resources behind her. It’s likely she was the first person in the world to do systematic scientific observations of a large mammal in the wild. It wasn’t until four years later that Jane Goodall first went to Tanzania to study chimpanzees.

But, unlike Dr. Goodall, Dr. Dagg’s trip did not make her famous. In fact, after she got her PhD, taught for several years and published in peer-reviewed journals, the University of Guelph rejected her tenure bid in 1972.

“As I say in the film, that decision ruined her career,” says retired U of Guelph zoology professor Sandy Middleton, who sat on Dr. Dagg’s all-male tenure and promotion committee. He says he was the only one to vote yes. So Dr. Dagg worked part-time at the University of Waterloo and, on her own time and own dime, produced a steady stream of articles and books about animals, the environment, and gender inequality in academia and science. “It’s just who I am,” says Dr. Dagg of her productivity as a self-proclaimed citizen scientist. “I’ve always got to be doing something.”

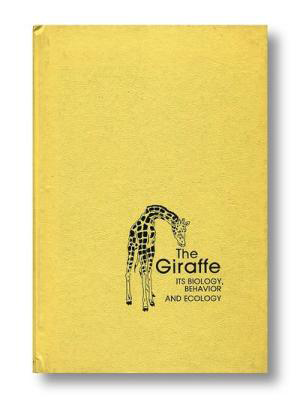

Tenacity, work ethic and curiosity allowed Dr. Dagg to carve out a career, which ended up being one of quiet importance. While she always knew it had sold well, she only found out recently that her 1976 book, The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior, and Ecology, has been dubbed “the bible” by giraffe biologists around the world. “It is the standing volume of work on the subject. Even to this day, that is the book,” says Jason Pootoolal, a zoologist based in Cambridge, Ontario, who worked with giraffes while on staff at the nearby African Lion Safari animal park.

Tenacity, work ethic and curiosity allowed Dr. Dagg to carve out a career, which ended up being one of quiet importance. While she always knew it had sold well, she only found out recently that her 1976 book, The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior, and Ecology, has been dubbed “the bible” by giraffe biologists around the world. “It is the standing volume of work on the subject. Even to this day, that is the book,” says Jason Pootoolal, a zoologist based in Cambridge, Ontario, who worked with giraffes while on staff at the nearby African Lion Safari animal park.

Dr. Dagg was the first in the world to publish observations of homosexual behaviour in animals. She called out biologists for imposing human social values – and sexist motifs – on their descriptions of animal behaviour. Meanwhile, her work on gender discrimination in academia charted wage inequality and how things such as anti-nepotism rules at universities discriminated against the wives of faculty members. “She’s very much about publishing and getting the knowledge out there, without any spin on the facts. She’s such a trailblazer,” says Mr. Pootoolal.

Now, Dr. Dagg is getting her due via apologies, awards and applause. Although some would say it’s too little, too late.

Anne Innis, born in 1933, seemed destined for academic life – and, indeed, all four Innis children did graduate-level study. Her father was Harold Innis, the acclaimed professor of political economy who has a college named for him at the University of Toronto. Mother Mary Quayle Innis was a prolific author and editor who served as dean of women of University College at U of T. Mary took three-year-old Anne to the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago, where she saw her first giraffe. “From then I wanted to know more and more about this wonderful creature,” she wrote in her 2016 memoir, Smitten by Giraffe, published by McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Anne Innis, born in 1933, seemed destined for academic life – and, indeed, all four Innis children did graduate-level study. Her father was Harold Innis, the acclaimed professor of political economy who has a college named for him at the University of Toronto. Mother Mary Quayle Innis was a prolific author and editor who served as dean of women of University College at U of T. Mary took three-year-old Anne to the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago, where she saw her first giraffe. “From then I wanted to know more and more about this wonderful creature,” she wrote in her 2016 memoir, Smitten by Giraffe, published by McGill-Queen’s University Press.

After high school at Bishop Strachan School (painter Robert Bateman was her first boyfriend back then, she recalls), a degree in biology and a master’s in genetics at U of T, Anne began plotting her trip to Africa. One of her professors suggested she write to a ranch manager he’d heard of in South Africa, and she did so, signing the letter A. Innis – previous inquiries had been rejected because she was a woman.

At the Fleur de Lys ranch, Anne took detailed notes on what giraffes were doing at five-minute intervals, charting about 30 creatures every day. She collected leaves from the trees that they ate from to understand their diet. Despite the heat, she stayed inside the Ford Prefect she’d bought for $200, because if they saw her outside the car, the giraffes changed what they were doing. This was in contrast to how Dr. Goodall conducted her field research. “She had the chimps in her tent and they were playing games. That’s just exactly what I would never do,” says Dr. Dagg. She also ignored the rules of segregation, and the acerbic comments, when she struck up friendships with Black people on the boat to and from Africa, and became close to two Black children on the ranch.

After the trip, in 1957, Anne married physicist Ian Dagg, who shared her love of tennis. He took a faculty job at U of Waterloo. She taught and did her PhD in animal behaviour at the same university, and the couple had three children. She recalls the children climbing on her lap and wanting to help as she analyzed film recorded while in Africa – Ian had taped strips of film to the walls of Anne’s office so she could examine the giraffes’ gait, eventually discovering that they could not trot.

children (left to right) Mary, Ian and Hugh.

A year after completing her degree in 1967, Dr. Dagg landed a job as an assistant professor at U of Guelph. By the time she’d applied for tenure, she had about 20 published articles on topics such as giraffe behaviour, their food preferences, the locomotion of various animals, and the bird population in the Waterloo Region, in publications that included the Journal of Zoology, the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Mammalia and the Canadian Journal of Zoology.

Her tenure committee claimed her research program wasn’t fully established and she hadn’t been published in prestigious publications. “That was really a cop-out as far as I was concerned. Women didn’t fare well in my department,” Dr. Middleton says, recalling how one woman got tenure around that time, but her husband worked in a key technical role for the dean. A few years after Dr. Dagg’s rejection, another well-qualified woman also got turned down.

“That was the end of everything I had ever hoped for,” Dr. Dagg says in The Woman Who Loves Giraffes. U of Waterloo had already made it clear that they would not hire married women for full-time positions. She applied to Wilfrid Laurier University, but a man with a less impressive resumé got the job. Dr. Dagg launched a complaint with the Ontario Human Rights Commission. The case dragged on for years, and she lost.

“I recall in the 1970s mom being very depressed,” says her daughter, Mary Dagg. Amy Phelps, an animal scientist at the San Francisco Zoo who knows Dr. Dagg, says: “It would have been easy to pull the ‘poor me’ card. But she just used it to fuel her fire.” Dr. Dagg founded Otter Press, publishing a book of her husband’s work, her own first book, Mammals of Waterloo and South Wellington, and many others. She drew on her notes from Africa to write The Giraffe along with former classmate Bristol Foster, putting it out with a U.S. publisher.

enclosure at Brookfield Zoo in Chicago.

By 1978, Dr. Dagg had found part-time work with the integrated studies program at U of Waterloo. It was later called independent studies and at one point she worked as its program director. She served as Cory Doctorow’s advisor in 1992. Now a science fiction writer and journalist, Mr. Doctorow wanted to write his tech-focused thesis in hypertext and submit it on a CD-ROM. “She went to bat for me,” he recalls. The school refused, insisting he file on paper. “While she was always bullish on academic rigour, she’s also not constrained by convention,” he says.

She kept writing and publishing, and that work was kept quite separate from her teaching. “No one talked to me about it, ever,” says Dr. Dagg, referring to her colleagues at U of Waterloo. “No one asked me, ‘What are you doing?’ because they would assume I wasn’t doing anything.” Mary thinks her mother’s tireless work ethic came from her upbringing. “Her father was always working, her mother was always working. Being at home working and writing books was just what you did.” Along with a second edition of The Giraffe in 1982, Dr. Dagg published dozens of articles and a total of about 20 books throughout her career, and new books are still coming out, including children’s books on animals and one about her mother.

Over the years, Otter Press became marginally profitable, and Dr. Dagg made a bit of money as well from her teaching and writing. She would often say to her kids, “I take care of the travel.” Indeed, she would finance all the family’s trips while Ian’s salary paid the regular bills.

When Ian died suddenly in 1993 – he collapsed from a heart attack during one of their Friday night tennis games – Anne kept on with her writing and advocacy work. She later reconnected with an old university friend who’d also been widowed, political science professor Alan Cairns, and they were common-law partners until his death last year.

While Dr. Dagg came up against blatant sexism in her dealings with universities, the subject of her research may also have proved a barrier. “Giraffes were thought of as these big, stupid, beautiful cows,” says Ms. Phelps in San Francisco. “They were not given the same level of serious study that you see for the great apes and elephants and large carnivores.” Jonathan Newman, dean of the college of biological science at U of Guelph (until August 1), says giraffes can be a challenge to study. “The bigger the animal, the harder it is to do good science, to get replication,” he says. Plus, they tend to live far from Canada.

As a poorly funded citizen scientist, Dr. Dagg managed to look past her first love and began tackling another topic: sexist assumptions in science. In 1983’s Harems and Other Horrors: Sexual Bias in Behavioral Biology, she calls out (mostly male) scientists for imposing their gendered ideas on animals, such as describing mating behaviours in females as “coy” or “flirtatious.” Years later, an ongoing argument via journal articles about infanticide among lions with U.S. biologist Craig Packer – during which he called her a “fringe scientist” with a “bizarre obsession” – led to the 2004 book ‘Love of Shopping’ is Not a Gene: Problems with Darwinian Psychology. In it, she links assumptions about animals, the inevitability of war and the inferiority of women and minorities, to flaws with Darwinian psychology.

“That book was transformative for me,” says Mr. Doctorow, who reviewed it. “I realized I had accepted some ideas that didn’t hold up to even the thinnest veneer of scrutiny,” he says. “I still talk about that book to people.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Dagg’s negative experiences in academia – including realizing that she and other female part-time instructors were being paid less than the men – drew her into writing about gender issues in academia. Her 1988 book, MisEducation: Women and Canadian Universities, used surveys and statistical data to map out the extent of sexual discrimination at Canada’s universities. Her 2001 book, The Feminine Gaze, celebrates the works of female non-fiction writers in Canada.

“Part of me thinks it was actually a good thing,” says daughter Mary of her mother not getting tenure. “It means she focused so much on another huge issue, which was getting women respect in the world, not just at universities but on every level.”

About a decade ago, Ms. Phelps, who was then working with giraffes at the Oakland Zoo, helped form the International Association of Giraffe Care Professionals and began planning the group’s first conference in Arizona for 2010. She wanted the author of the giraffe book she’d been carrying around since she was a teen to attend. “This woman was so important to us … but nobody knew her,” says Ms. Phelps.

She enlisted the help of animal behaviour consultant and former police officer Lisa Clifton-Bumpass. The two had been training an arthritic giraffe at the zoo to comply with treatments to relieve its pain. Since Ms. Clifton-Bumpass had never worked with giraffes prior to that, the first thing Ms. Phelps did was give her a copy of The Giraffe. Ms. Clifton-Bumpass did some digging, found Dr. Dagg’s contact information and Ms. Phelps got in touch.

When Ms. Phelps learned what her idol had been through, getting her to the conference was more urgent than ever. “It was really important that her story be told and that she be given the respect she’d been denied for 50 years.” Dr. Dagg showed up, made a presentation and received the Pioneer Award (conference organizers renamed it the Dr. Anne Innis Dagg Excellence in Giraffe Science Award after that, and give it out annually). “She was kind and gracious and I think she was genuinely shocked that, to all of us, she was this amazing hero,” says Ms. Phelps. Mr. Pootoolal was at the conference and remembers her being courteous with him. “She’s the queen of giraffes and there she was acting so humble,” he says.

The event got Dr. Dagg connected with the who’s who of giraffe biology around the world. “It’s really nice. When I go to a conference, I know a lot of people and they know me,” she says. “She was re-energized,” says Mary. “She had been digging around and doing her own things and not realizing it was resonating with anybody. She was operating in a bit of a bubble.”

That bubble has since undeniably popped. In 2011, the CBC radio program Ideas did a piece on Dr. Dagg, which caught the attention of filmmaker Ms. Reid, who first proposed a scripted movie about the researcher but altered her plan and started work on the documentary.

Meanwhile, Cambridge University Press wanted a new edition of the giraffe book. Dr. Dagg tapped her newfound colleagues for the latest research. “I can phone them if I don’t understand something,” she says. Before it came out in 2014, Dr. Dagg wrote a piece for The Globe and Mail that explained her errors regarding social behaviour and anatomy in earlier editions. “She admitted she was wrong,” marvels Ms. Phelps.

Around the same time, at long last, she went back to Africa. Ms. Clifton-Bumpass, herself smitten by both Dr. Dagg and giraffes, proposed a trip to Kenya in 2013. Two years later, she returned to Fleur de Lys, now cut up by paved roads and with a dramatically smaller giraffe population. The same year, she contributed to a segment on giraffes for CBC’s The Nature of Things that highlighted their dwindling numbers. In 2016, she released her autobiography, Smitten by Giraffe.

Now, with the recent documentary, Dr. Dagg’s story has spread wider still, and the acknowledgments and awards keep coming, including one from her alma mater Bishop Strachan. U of Guelph hosted a screening of the film this past February where Dr. Newman spoke, reading an official apology from Charlotte Yates, the provost and vice-president, academic, and announcing the creation of a summer research scholarship in Dr. Dagg’s name. “Our goals were to allow the college community to engage with the film and with Anne afterwards, and also for us to say we’re sorry for how things worked out for her,” says Dr. Newman.

This late-in-life redemption clearly feels bittersweet to Dr. Dagg. “They had to, really,” she says of the university’s apology. “Pretty much everyone is saying, ‘this was terrible.’” Mary says the film may have opened old wounds for her mother, who rewatches it at every screening. “Each time, she gets riled up again about the whole Guelph thing.” Dr. Dagg refers to the dean behind her tenure refusal as “the horrible guy” and says it’s “just disgusting” that it was mainly men who held faculty jobs at the time.

Dr. Dagg’s house is full of giraffes – a huge stuffed toy giraffe, giraffe mugs, a painting of giraffes by long-time pal Robert Bateman – but she missed out on decades of working with them, and to protect them. “I’m happy to introduce her to the younger generation of female zookeepers, to remind them that the door was not always open,” says Ms. Phelps. “There were women who beat on that door with blood, sweat and tears to open it.”

Yet many other slighted female academics will never get their due. “There are a lot of other stories out there about women like Anne who did significant work and never got the recognition for it,” says Ms. Reid. Dr. Dagg now humbly embraces her superstar status, and looks back on her life’s work with a new perspective. “I feel much happier now. I feel now that what I was doing was something important.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

11 Comments

Big surprise. And yes, it’s still happening. Even in professions that are female-dominated, like librarianship. The profession itself is about 80% female, and the heads of large urban libraries and R1 research institutions are over 50% male. It’s getting better. It used to be they were over 80% male. But it’s still ridiculous.

Thanks Diane for the wonderful and thorough article on Anne! I am the filmmaker who made the documentary about her that you mentioned in your article. If people are interested in seeing The Woman Who Loves Giraffes, it is available on iTunes in Canada. Here is the direct link:

https://itunes.apple.com/ca/movie/the-woman-who-loves-giraffes/id1468418195

Best, Alison

Remarkable and moving documentary , have just watched on Crave tv. it’s people like Anne, who’s never ending commitment , care and love for Giraffes gives hope for their survival.

Thank you Anne.

xx.

I am watching that biography right now on CTV, Dec 26, 2019. Giraffes are one of my loves. My father was a biologist also, so I have also had a love of animals and forestry.

I have a separate question … is there any way to contact Dr Dagg by email. My father was head of biology dept at Wilfred Laurier University from mid 1960’s into ’80’s. I am wondering if she knew him – Dr DA MacLulich. Thank you for considering this.

Dr. Innis Dagg was my advisor in the University of Waterloo Independent Studies programme. She took a chance on me – a high school dropout – and helped me transform my life. I went on to complete graduate degrees and become a scientist. I credit her for me taking that path. I never could understand her being overlooked because she was such an outstanding researcher and academic. I am so grateful to Dr. Innis Dagg for everything she did for me (and the world) and am so pleased with her recent Order of Canada appointment. Congratulations.

Dr. Dagg’s life story is so inspiring – proof that you should focus on your passion projects, and the accolades will ultimately find you. The documentary, The Woman Who Loves Giraffes, tells her story so beautifully, thanks to Alison Reid.

Just watched the documentary and I am in such awe of Dr. Dagg that I would love to send her a note of congratulations and admiration, how can that be accomplished? I am a retired translator, born in Mexico, educated in Europe and Canada and currently living in the Chicago area in the U.S. Thank you so much for any assistance you can provide.

I watched the documentary today. It prompted me to Google this amazing lady. I have read your article.

I worked in the nuclear power sector for 20 plus years. It was an amazing dynamic environment to work in. Such a diverse knowledge base in physics, mechanics, chemistry and analysis.

It is a very hard place for woman to work in. At least 25 men for every woman. You certainly have to develop what my grandmother use to call “tough skin”.

I am so very proud of Anne. My heart is filled with pride. I wish that i knew of some of her podium moments where i could have heard her speak.

So many silent tears from woman of her stature. God certainly loves her very much. She has endured so much…but has held Africa in her hands and heart. She is certainly loved.

I watched the film ”The Woman Who Loves Giraffes” today and I loved it!! What an amazing woman who was seldom recognized for her lifelong work simply because she was a woman!!

Bravo Anne!!!

Paddy Campbell

Calgary

What a wonderful person–a Canadian I regret I knew nothing about.

Joe Hudson, Calgary

As a woman, I received the very same treatment in the 1970s. Men, with lesser qualifications were pushed ahead of me & they had absolutely no compunction to state that it was because I was a woman. I might get pregnant was their favourite one. As it was I did & I taught to the end of the day before delivery & I was teaching again an hour after returning from the hospital after that delivery. I still can not figure out what THEIR problem is/was?

From my Grandmother’s time in the 1900s fighting with Nellie McClung for votes for women, males were still dominating. They are fearful of educated women, always have been & always will be.