Seeking an exit from entrance scholarships

There’s little evidence that automatic entrance scholarships persuade students to accept an offer of admission. Could the funds be better spent elsewhere?

It’s the message she’s been hoping for. There’s a whoop of joy, a happy dance and texts fired off to parents and friends announcing the good news.

A young person has been accepted into her university of choice and offered a few thousand dollars in scholarship money to sweeten the deal. For the student and her family, a scholarship can be seen as formal acknowledgement that years of academic striving have been worth it. Among some high achievers, it can be an expectation.

For universities, though, entrance scholarships are less of a pat on the back than a calculated tool to meet recruitment priorities. Those priorities may include ensuring enough “bums in seats” in a competitive regional marketplace or snagging the best and brightest before somebody else does in the global chase for the most promising young minds.

It’s unclear how much Canadian universities spend on entrance scholarships – the amounts are not broken out from the global numbers reported by the Canadian Association of University Business Officers encompassing bursaries, other undergraduate scholarships and graduate student awards. In 2014-15, the global amount was close to $1.9 billion, and funding for graduate students takes the lion’s share.

Still, it’s safe to say that entrance scholarships absorb tens of millions of dollars a year, and possibly more than $100 million, drawn from operating and endowment funds. Yet, it’s an unanswered question as to whether the money – especially funds guaranteed to students based solely on their high school grades – is recruiting the type of students that the universities would like.

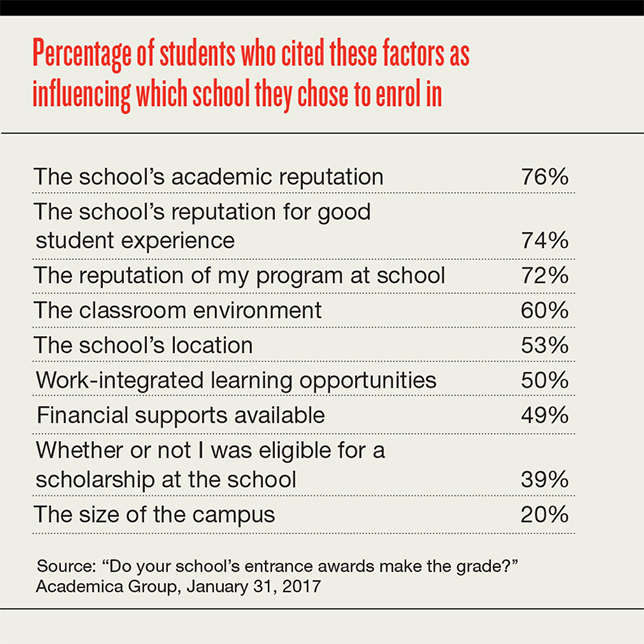

Last fall, nearly 1,100 Canadian undergraduate students were surveyed jointly by Academica Group, a research and consulting company, and ScholarshipsCanada.com, part of the SchoolFinder Group, to discover whether the offer of an entrance scholarship had any effect on students’ enrolment choices. The survey found that while more than half of students said they had been offered a scholarship, only 39 percent said their eligibility for one had been a factor when they chose which institution to attend. Just three percent of students were “flipped” away from their first choice of school due to a scholarship offer.

In fact, a school’s reputation for academic excellence and good student experience was valued far more highly than an entrance scholarship. Most scholarships were worth less than $2,500 and were only for the first year of study, leading the survey report to suggest that institutions should consider offering fewer scholarships at a higher value to attract the students they really want.

Alex Usher, president of the consulting firm Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA), says it is common for 60 percent of an incoming undergraduate class to arrive with some form of entrance scholarship. More than anything else, it is an “admissions management” tool, he says, designed to get a student to commit earlier to an institution. “Students have a pretty good sense of which institutions they want to go to, so using these awards to try and change their mind is actually kind of difficult.”

That was Robert Burroughs’ experience as a prospective undergraduate. Despite receiving a $4,000 renewable entrance scholarship from Mount Allison University in 2009 – good money, but less than the offer from an Ontario university – it was the Atlantic institution’s reputation and its promise to him that were the deciding factors. Acknowledging his excellent high school record, “they told me that they would enrich me. They would grow me,” recalls Mr. Burroughs, now executive director of the New Brunswick Student Alliance, “which are all the right words that you want to be hearing.”

Guaranteed or “automatic” entrance scholarships that first-time students don’t have to apply for are found across the country but are especially prolific in university-rich Ontario, where their popularity soared in the late 1990s. That was a time when tuition fees climbed rapidly in many provinces due to federal funding cuts. From a handful of Ontario universities offering them in 1994, some 15 of the province’s 19 universities were providing “automatics” to students whose high school marks averaged 80 to 90 percent, according to research published in the Canadian Journal of Economics in May 2012.

Most universities continue to post grids online, spelling out guaranteed amounts of entrance scholarships based on students’ high school grades. These range from $500 for an 80-percent average to a student’s entire tuition for a 95-percent average. Students receive the scholarship as long as they accept the university’s entrance offer by a specified deadline.

When such scholarships are so common yet seem to have such little real impact, some people are asking whether the funds couldn’t be better spent.

One student-aid manager says she wishes there weren’t any entrance scholarships, apart from the very prestigious ones that students have to apply for (and which are often financed by privately raised endowment funds, not by operating funds). In that way, a university’s student-aid funds could be freed up to address each student’s unique need, rather than several million dollars being committed to a grades-based program with nebulous returns. “We do it because every other university does it,” says the manager, who wanted to remain anonymous.

The Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance is calling on the Ontario government to stipulate that institutional operating funds be used only for needs-based student financial aid, not for merit-based scholarships. Research that OUSA, an alliance of eight student associations, published in 2014 says that most students received a merit-based scholarship, but those whose family income was below $25,000 received the lowest amount. The highest-income students averaged $547 more.

Part-timers and students with dependents are among the students who fare the worst in securing entrance scholarships, says Jamie Cleary, OUSA’s immediate past-president. That’s because the eligibility criteria favour students freshly out of high school who enrol in full-time studies. The student alliance plans to raise the issue in Ontario’s next round of tuition framework consultations.

Mr. Usher, the higher education consultant, has mused in the past that governments could put an end to this automatic entrance-scholarships “arms race” that no one likes but no one wants to be the first to quit. However, more recently, he said that a government move on this front is unlikely: “The politics of ‘stop charging those students so little’ is not going to wash anywhere.”

Still, after more than 20 years battling in the entrance scholarship trenches, and faced with changing finances and recruitment objectives, some universities have been adapting their programs on their own.

The University of New Brunswick spends $2.5 million annually on entrance scholarships, funded equally by operating and endowment money. However, it eliminated automatic entrance scholarships over the past five years. About half of the incoming class still receives a scholarship, but students must submit a scholarship application to be considered.

Under the previous automatic system, the entrance scholarship became “an expectation,” says Victoria Sparkes, director of undergraduate awards. And scholarships remain a top reason for students choosing UNB, she adds, contrary to the results of the survey conducted by Academica and ScholarshipsCanada.com.

“Our statistics support the feedback we’ve had, which is that the program is being received very positively and our refusal rates [to offers of admission] have actually decreased, which is what you want to see,” says Ms. Sparkes.

Similarly, the University of Toronto’s main campus used to award $2,000 automatically to students entering with a grade average higher than 92 percent (in addition to other scholarships students may have applied for and won). U of T ended those scholarships as of this fall, using the money for a one-time, $7,500 award for 500 to 700 incoming students across all campuses, called UT Scholars; the mark cut-off is higher than previously and is determined by the student’s program. U of T’s two suburban campuses in Mississauga and Scarborough continue to offer automatic scholarships to students with a lower grade minimum.

In total, U of T is spending roughly $15 million on entrance scholarships, compared to $87 million to meet financial need for all students, says Richard Levin, executive director, enrolment services and university registrar at U of T.

Mr. Levin says the previous way of doing things was expensive and, according to recruiters and admissions staff, “students were finding it really wasn’t enough money to make a difference. For some students, any award is some level of prestige, but we just didn’t see that reflected in the decision to choose us or not to choose us.”

For similar reasons, the University of British Columbia eliminated “automatics” in 2012. It reinvested the $6.1 million dedicated to these entrance scholarships into other forms of support, such as its Go Global international experience and work-study programs. Last fall, UBC used donor and institution money to create the Centennial Scholars program, giving up to $10,000 a year to 100 domestic, academically qualified students with financial need. Ten of them receive a “full ride” scholarship of up to $20,000 a year to cover tuition fees and living expenses, addressing the issue that free tuition isn’t always enough to persuade students to change their school choice. If accepting an award means moving to a new city, students can still be left in deficit if their living costs aren’t covered.

“We were able to achieve the diversity goal we were striving for in terms of [students] coming from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and all different backgrounds,” says Kate Ross, UBC’s registrar and associate vice-president, enrolment services, who has personally donated to Centennial Scholars. “They are a wonderfully fascinating group of young people. Our plan is to continue to build that.”

Also about five years ago, neighbouring Simon Fraser University hiked its cut-off marks for automatic scholarships to an average above 95 percent. This led to fewer automatic awards with a higher value, $5,000, for one year. But the school’s data showed that this wasn’t making a difference. Even a $12,000 scholarship over two years wasn’t changing the minds of top-tier students who hadn’t already made SFU their first choice.

“We said, ‘We’re not thrilled with the outcomes and we also don’t think that it’s well-aligned with our approach to recruitment,’” says Rummana Khan Hemani, SFU’s registrar and executive director, student enrolment.

SFU wanted to attract a greater diversity of students, but its traditional scholarship criteria – stratospheric marks, extracurricular and community service participation – seemed to discriminate against worthy students who were less privileged and hadn’t had the same opportunities to acquire all the typical CV extras.

This fall, SFU plans to unveil a radically different program to address both problems – attracting the best students and attracting more diverse, worthy students. The program will offer flexibility to tweak things as needed. Minimum GPA renewal criteria will be eased so that students don’t feel under extreme pressure to maintain high marks, a common concern with renewable scholarships, say some observers and researchers.

“We want to be able to level the playing field,” says Ms. Hemani. “We want a good mix of students and what we don’t want is a scholarship program that only benefits the privileged.” Non-monetary perks will be part of SFU’s new package.

Increasingly, non-monetary benefits are found at other schools too. McGill University traditionally offered its automatic scholarships only to very high-achieving students (currently a one-time, $3,000-scholarship to students averaging above 95 percent), but it also guarantees recipients’ first choice of residence and gives them front-of-the-line course registration privileges. It has added an optional mentorship program this year, pairing recipients with McGill alumni.

The University of Windsor, serving a predominantly local catchment, has had an Outstanding Scholars program since 2002, pitched at the top 100 students in the incoming class. The cash reward is small – $1,500 in the first year, and that may eventually be eliminated – but the program provides something scholars, faculty and even students view as more valuable: the opportunity to work on paid research projects with a U of Windsor faculty member after first year. In this way, students can earn up to $1,500 a semester and gain priceless research experience for their CV.

Andrea Yzeiri, a U of Windsor business and political science student, hasn’t yet graduated but her name is on a co-authored abstract, thanks to her Outstanding Scholars placement with management science professor Mohammed Fazle Baki. She presented the research, about a tool to pinpoint inefficiencies in the healthcare industry, with Dr. Baki at an international conference on industrial engineering and operations management in Detroit last fall. As a result of the experience, she’s considering pursuing a doctorate.

“How many universities can we say are giving top [undergraduate] students the opportunity to do research with faculty?” she says. “This program has changed my life and changed my outlook on where I want my education to go.”

Programs like these are ways that universities can give themselves an edge when it comes to competing for the students they most want, says Mr. Usher of HESA. Putting some of the money tagged for scholarships into student support and other services may also help, something the survey report suggested, too. Such support could include reduced residence fees and early acceptance to work-study positions. “You want to get undergraduate students? Tell them that you’ve got their back,” says Mr. Usher.

People interviewed for this story don’t envision an end to automatic entrance scholarships but they say these awards may diminish in importance. Universities that have already made changes to their programs say that those who want to build a case for change should examine their recruiting and take-up data to understand what’s working and what’s not.

With that data in hand, scholarship offerings can be designed to respond to a university’s special circumstances, whether it’s a large well-known university competing internationally for Ivy League-ready students or a small institution among several others, all recruiting students from the same region. The changing nature of undergraduate students has to be taken into account, and students’ needs and desires may vary among international students, Indigenous students and students who are the first in their family to attend university.

“The scholarship should help an institution attract that student to come,” sums up Ms. Hemani at SFU. “If you can’t do that with your scholarship and you have to go down to the 10th student on the list, you’ve got to figure out what’s going on.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.