The tale of two pandemics

What the history of pandemics can tell university leaders about the aftermath of COVID-19.

Multiple times pandemics have gripped the world, interrupting the social and economic networks of untold millions, and sometimes altering the societies they spread through, their cultures and their institutions. The university is one of those institutions that pandemics have affected in significant ways and to a degree that not many people today realize.

The following is a brief historical probe into the impact of the Black Death (14th century) and smallpox (19th century) on universities. Invoking historical analogies does not imply that COVID-19 will impact the future trajectory of universities in the same way the diseases in question did. After all, we live in a much different era scientifically. I use history here in an attempt to discover patterns or underlying principles that govern the actions and perceptions towards higher education in the aftermath of a major health and economic crisis like the one we are undergoing.

Broadly, whatever the texts you read on the history of pandemics, the naked facts stare you in the face: pandemics bring in their train outbreaks of panic, unhappiness and uncertainty which oftentimes drive institutions to take counterproductive measures and waste resources. This is primarily because pandemics are totally different from traditional risks. They afflict society capriciously, and thus they are outside the scope of issues typically considered by university strategists or business continuity planners. The history of pandemics may have lessons for those campus leaders interested in mitigating losses and charting a rational pathway for their institutions after COVID-19 has ebbed away and disappeared.

The Black Death

The Black Death (1347-1352), or the plague, caused a marked decline in the medieval university. Depopulation was the first consequence. Professors and students fled for safety, leaving behind them empty campuses. Appealing to the bishops for assistance in reviving Oxford, Edward III describes how the university had become desolate, “like a worthless fig tree without fruit.” Low enrolment continued unabated for the next several decades. The historian Father Denifle counts as many as five of the 30 universities that existed before the plague disappearing by the end of the 1350s due to low or no enrolment.

But Denifle also observes renewed interest in universities amidst efforts to counteract the plague. And before the end of the 14th century, he mentions 15 new universities established through endowments from Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, and three successive popes. The plague generated other beneficial results for universities. For example, in The Black Death and Men of Learning, Anna Campbell finds that donations rose significantly because of the plague in efforts to renew the supply of clergy lost to the pandemic. Colleges such as Trinity Hall at Oxford and Corpus Christi College at Cambridge owe their existence to this dynamic.

The time and reasons for endowments and donations also changed. Before the plague, they were mostly given by persons with serious health problems, usually close to death. After the plague, endowments and donations from healthy individuals increased substantially. People probably began to see worthwhile earthly services the university can provide, rather than simply praying for the salvation of their souls after they’re gone. Donations and endowments were institutionalized as a common practice.

The plague also triggered reforms to rid universities of bad management and corruption. These reforms gave greater recognition to student rights. And, due to the scarcity of Latin teachers, universities began to recognize vernacular languages as the medium of instruction. In the realm of thought, a major development accelerated by the Black Death was the recognition of non-university-based cultures, particularly the so-called Italian humanism which paved the way for the Renaissance.

Smallpox

Smallpox was as consequential for universities as the Black Death. But its impact was indirect, yet profound. The story of smallpox is bound up with Edward Jenner’s development of the first vaccine in 1796. Jenner’s empirical work on smallpox demonstrated the validity of knowledge derived from experience and observation. Jenner’s method consisted of infecting a healthy person with scabs taken from a sick person. After a rocky start, his method worked, and that inspired Jenner to develop the first vaccine in history.

Jenner’s success turned medical education on its head. It extinguished two dominant theories in medical practice: humouralism, the notion that sickness results from the imbalance of four humours (elements) of the body; and Galenism, which only accepted diagnosis based on abstract rules extracted from ancient texts. Professor Frank Snowden from Yale shows that Jenner’s success was a turning point, especially for medical epistemology.

Jenner revolutionized the understanding of pandemics by showing they are caused by entities external to the body rather than chemical disequilibrium. His method also reinvigorated interest in John Locke’s ideas and other enlightenment figures who held that knowledge can only be obtained through the rigorous examination of nature. The Medical School of Paris adopted Jenner’s empirical method and perfected it by establishing the hospital-university nexus and institutionalizing the direct observation of patients in their hospital beds as a standard practice in medical education. This diagnostic approach marks a moment of transition from medieval medicine to modern medicine based on empiricism.

Jenner’s success story reverberated throughout Europe and across the Atlantic. Influential people sought his advice on medical education and establishing vaccination as a public health strategy. These included Pope Pius VII, Napoleon Bonaparte, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Waterhouse – the latter of whom replicated the approach of the Parisian school in his home school, Harvard Medical School.

Napoleon in particular was a fan of Jenner, which was something Jenner used to free British soldiers captured by the French during the wars between Britain and France (1803-1815). In a correspondence, Napoleon wrote: “Jenner – we can’t refuse that man anything.” I presume this incident offers some hope for science diplomacy aficionados.

Lessons from the two pandemics

In both cases, there are patterns that can be observed about how people perceive universities, and learning institutions more broadly, during and in the aftermath of pandemic outbreaks. First, despite the heavy blow pandemics deliver to the economy and the general morale, governments and the public become more interested in universities. This is probably due to the fact that pandemics expose our weaknesses, and people seek refuge in science, which is the business of universities. I do believe that this pattern will continue with COVID-19, and the writing is on the wall. There are calls now for large-scale plans, Manhattan-Project style, to increase the global ability to fend off future pandemics

Second, pandemics generate interest in educational alternatives like the surge of attention online learning is receiving these days. The question is: Will online learning replace campuses? The current lockdown of universities provides social scientists with a natural experiment to test the hypothesis that online learning is the future. When COVID-19 emerged as a health crisis, universities managed to shift quickly to online platforms and continue with classes.

That said, I seriously doubt this renewed obsession with online learning will put the final kibosh on universities. Many people seem to be unhappy about remote learning, while others express concerns about the quality of learning being delivered.

We’ve seen similar predictions about online learning eclipsing universities with the advent of MOOCs (massive open online courses) in 2012. All turned out overstated claims and often hyperbole. The campus offers irreplaceable experiences. In short, the digital infrastructure is an area which universities need to consider to improve preparedness for exceptional circumstances, but spend wisely!

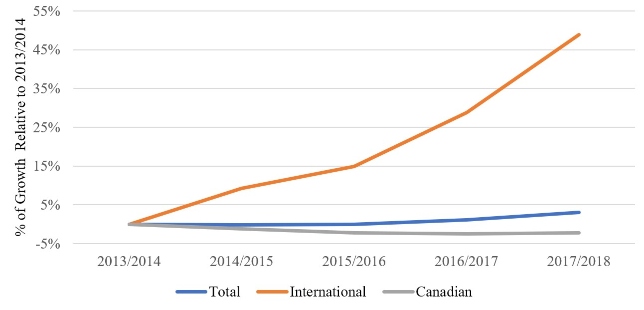

Third, pandemics affect enrolments. All enrolments? Not exactly. In Canada, for example, domestic enrolment has been low already for several years now (see Figure 1), while international students have been the fastest growing segment in the postsecondary population. Since 2013-2014, international enrolment has grown by 49 percent, whereas domestic enrolment decreased by 2.3 percent.

Source: By the author, based on Statistics Canada, Table 37-10-0086-01.

The future rates of international enrolment will depend on the measures and policies taken by governments in the receiving countries in the near future. Are there going to be travel restrictions on international students? If the answer is no, international students will keep coming, and for good reason.

Generally, Canadians have been too humane to deny access to their colleges and universities in recent decades. Let’s hope that world politics don’t escalate into a Second Cold War, as the historian Niall Furgeson recently suggested. The last Cold War (1947-1991) had adverse effects on the mobility of students and curtailed access to higher education between countries embroiled in this geopolitical tussle. I’d like to think the vast majority of Canadians don’t wish to revert to inhumane practices of this kind.

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

” Canadians have been too humane to deny access to their colleges and universities in recent decades.” No, we just make it so expensive that none but the children of the very rich can come. (While we enjoy much less expensive graduate education for our citizens in other countries.)