Canadian university libraries shine during pandemic

While most were able to seamlessly pivot to primarily online services, some also faced unique technological, licensing and human resource challenges.

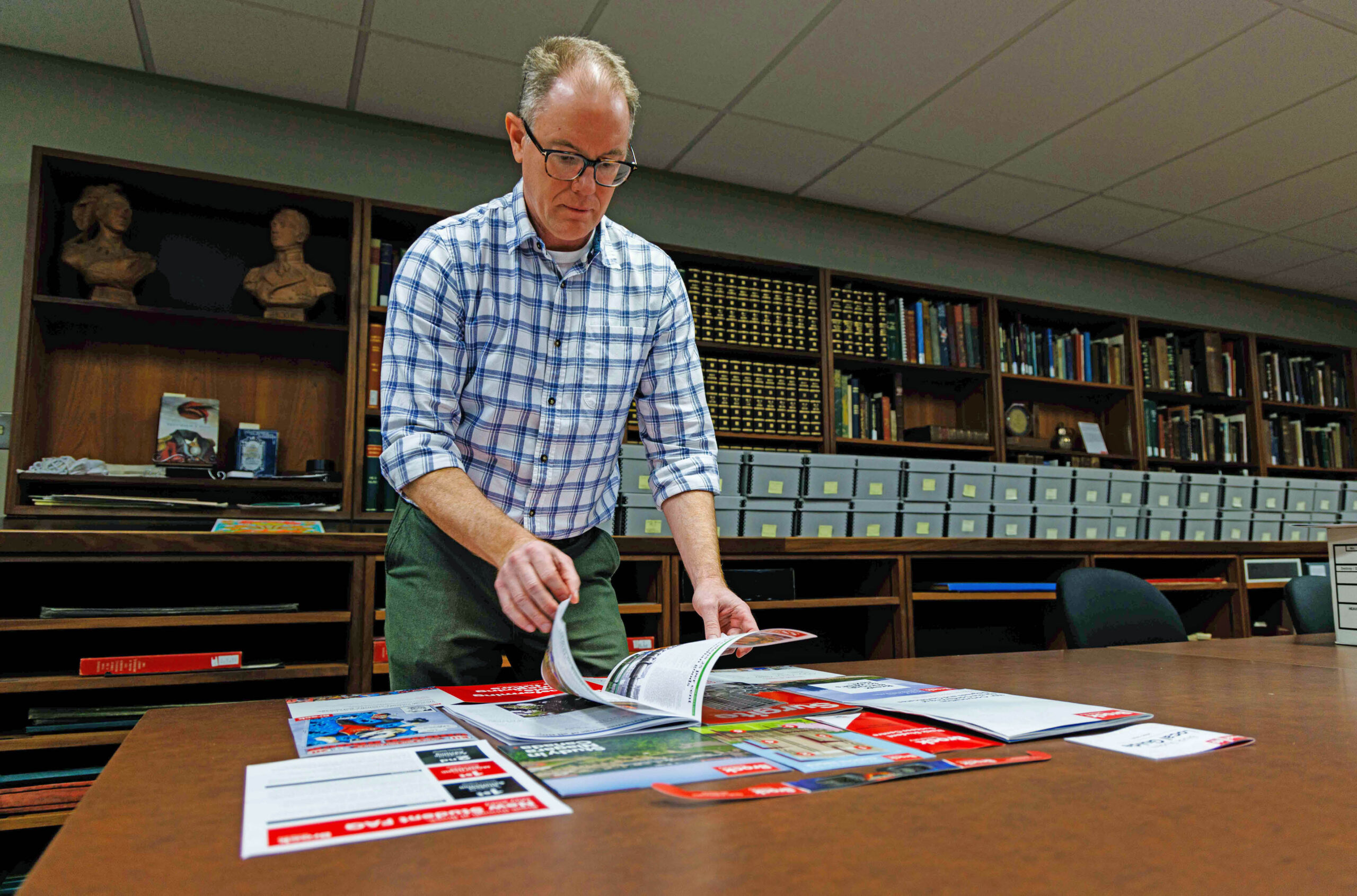

Larry Alford is rightly proud of the essentially glitch-free switch to electronic services that took place almost overnight when all 42 of the University of Toronto’s libraries and collections – the largest in Canada – closed their doors on March 24, 2020 due to the Ontario COVID-19 lockdown.

But the chief librarian’s most gratifying work of the pandemic started the next morning on his way to his office at the U of T’s Robarts Library, when he encountered a young student in the parking garage.

“She was sitting on the floor of the elevator lobby,” recalled Mr. Alford. “She had her laptop open along with some papers and a couple of books. I asked her why she was there, and she said for WiFi access. That made me determined to provide space for technology and WiFi for students who didn’t have access at home.”

It took six weeks of careful planning and preparation to meet public health guidelines, but small partitioned areas at two of U of T’s biggest libraries – Robarts and Gerstein – were eventually reopened for students in need.

Similar stories abound about the speed at which academic libraries across the country were able to overcome the many unique challenges posed by the pandemic in order to uphold their duty to support students and faculty in their search for knowledge.

Most are accolades for quickly pivoting to provide services in cyberspace – everything from access to electronic books, journals and article databases to live chat help – as well as special emergency services like curbside pickup for print materials and free on-request scanning services.

But university libraries also faced unique technological, licensing and human resource challenges that continue to reverberate across Canada’s academic landscape even as the pandemic wanes.

“We’re very proud of universities and how they have responded to this truly generational crisis,” said Vivian Lewis, the university librarian at McMaster University and president of the Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL), “But the pandemic has not been easy and has required a lot of heavy lifting.”

According to Ms. Lewis, the most dramatic change for university libraries since March 2020 – and also their biggest success – has been dealing with what she calls the “phenomenal uptick” in digital access to books, journals and other materials.

“One electronic book collection that would normally be accessed 50,000 times is now accessed 250,000 times,” said Ms. Lewis. She credited the ability of libraries to meet the sudden and sustained surge in demand to the decades and millions of dollars they have spent building up digital infrastructure.

“It’s important to understand that the publishing industry and consumption have been switching to digital for over 30 years,” said Ms. Lewis. “A lot of our staffing resources and budgets have gone into buying digital products and developing digital services to meet the needs of our students and faculty. That paid off early in the pandemic.”

In addition to their own collections, Ms. Lewis credits the emergency access many libraries were granted to other massive online book collections for helping students and researchers remain productive throughout the pandemic. One example is the HathiTrust Digital Library, a not-for-profit collaborative project with more than 17 million “digitized items.” Such licensing agreements were facilitated by the close personal and professional connections between academic research librarians across North America. But they will need to be renegotiated once the pandemic ends.

Because the vast majority of frontline library staff were already doing digital work, Ms. Lewis said it was easy for them to transition to work remotely from home when libraries closed. Other staff helped to provide curbside retrieval services for the vast, sometimes centuries-old print collections that students and researchers rely upon, especially in the humanities and social sciences. By reinforcing the notion of “digital first,” Ms. Lewis said the response to the pandemic is also driving the development of new strategies and policies regarding privacy, openness and the rights of librarians to preserve content. “It creates enduring value,” she said. “Accessibility is the key.”

Some university libraries hired more staff to ensure both online and in-person services both during the lockdowns and afterward. But when book stacks and other in-person services resumed, two Ontario schools – financially-strapped Laurentian University and the Ontario College of Art and Design University – let some library staff go. OCADU notably laid off four senior academic librarians with seven decades of service between them.

Kate Cushon, a librarian at the University of Regina and chair of the librarians’ and archivists’ committee at the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), says the firings are the most recent fallout from a decades-old issue: whether librarians and archivists are staff, or faculty members who enjoy tenure and job security.

“The pandemic exacerbated the problem,” said Ms. Cushon. “CAUT did two informal member surveys during the pandemic that found there was concern about possible layoffs.”

Though she hasn’t heard of labour strife at any university libraries other than the two Ontario schools, Ms. Cushon said the issue of employment status remains a thorny one on some campuses.

“It really depends on how much institutions value the role and professional skills that professional librarians and archivists bring to a school, and the experience of students and faculty members,” said Ms. Cushon. “I think the pandemic showed just how important we are to the fabric of the university community and especially to students.”

Sylvie Fournier agrees. As head librarian at Université de Sherbrooke, she says her facilities have proved to be both a lifeline and refuge for students during the pandemic, especially since last fall when students returned to a hybrid format of in-person and online learning.

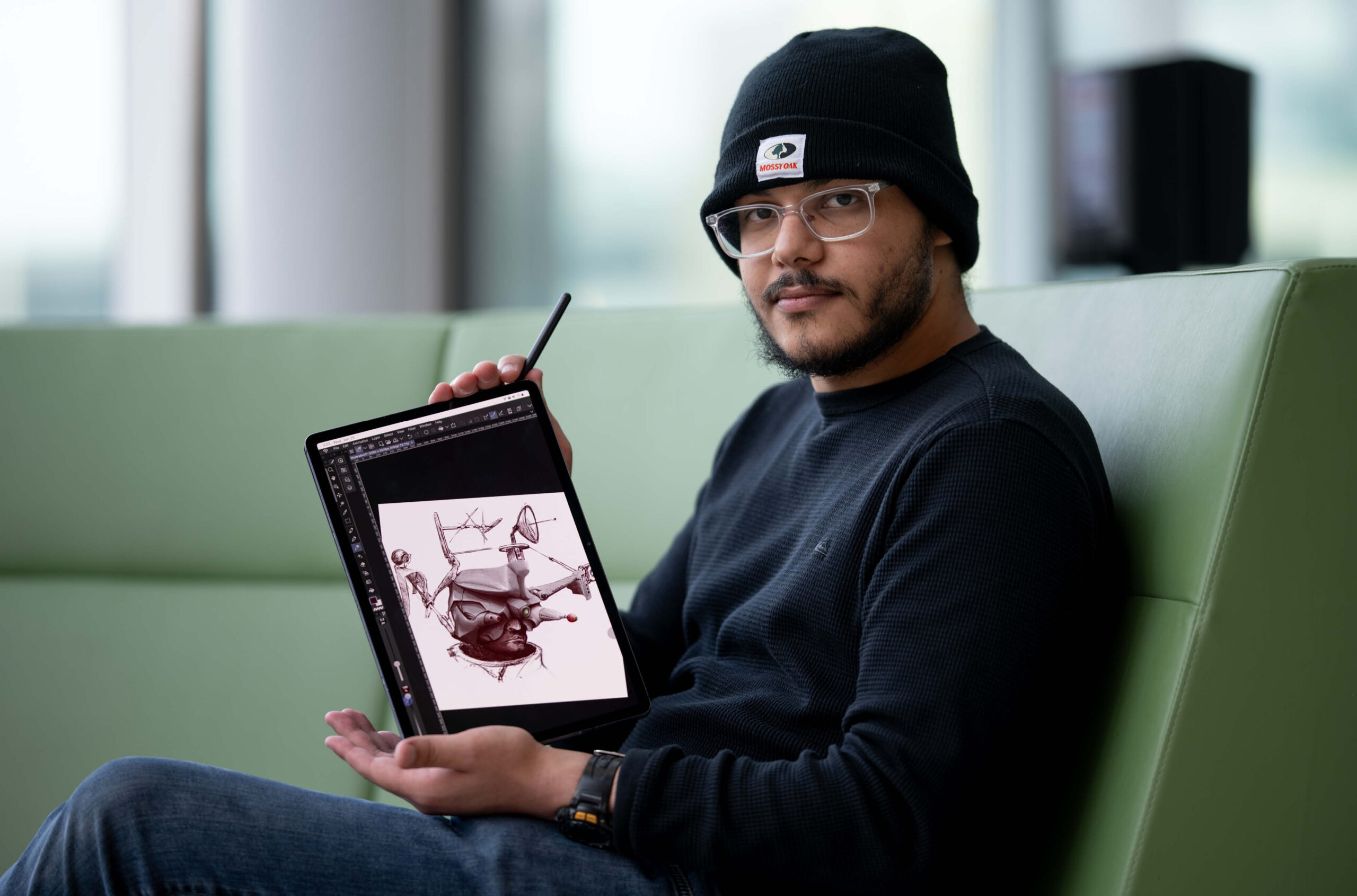

“We saw something we weren’t expecting: students with classroom teaching in the morning but [Microsoft] Teams classes in the afternoon,” said Dr. Fournier. “Many didn’t have time to go home so they needed a place where they could get WiFi and even access to computers and be able to talk. They instinctively came to the library, but we didn’t have those kinds of spaces.”

Dr. Fournier said she called several colleagues from other departments – many of whom she didn’t know and would likely never have met had it not been for the pandemic – and was able to quickly find spaces where headphone-wearing students could go to attend their online classes. Her library also created a webpage overnight to help students find those spaces.

“The camaraderie and dynamic team spirit that has been developed within the library and across the campus during the pandemic is exceptional,” said Dr. Fournier. “I’m both proud and happy with the work we did.”

Featured Jobs

- Research Chair in Systems Transformation and Family Justice (Faculty Position)University of Calgary

- Human Resources and Organizational Behaviour - Lecturer, 2-year termUniversity of Saskatchewan

- Creative and Cultural Industries - Assistant Professor (Fashion Studies and Cultures)Chapman University

- University LibrarianYukon University

- Architecture - Assistant ProfessorMcGill University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.