Latest settlement in CRC equity issue sets hard deadline for targets

If participating postsecondary institutions don’t meet their targets by the end of 2029, the number of research chairs they receive will be cut.

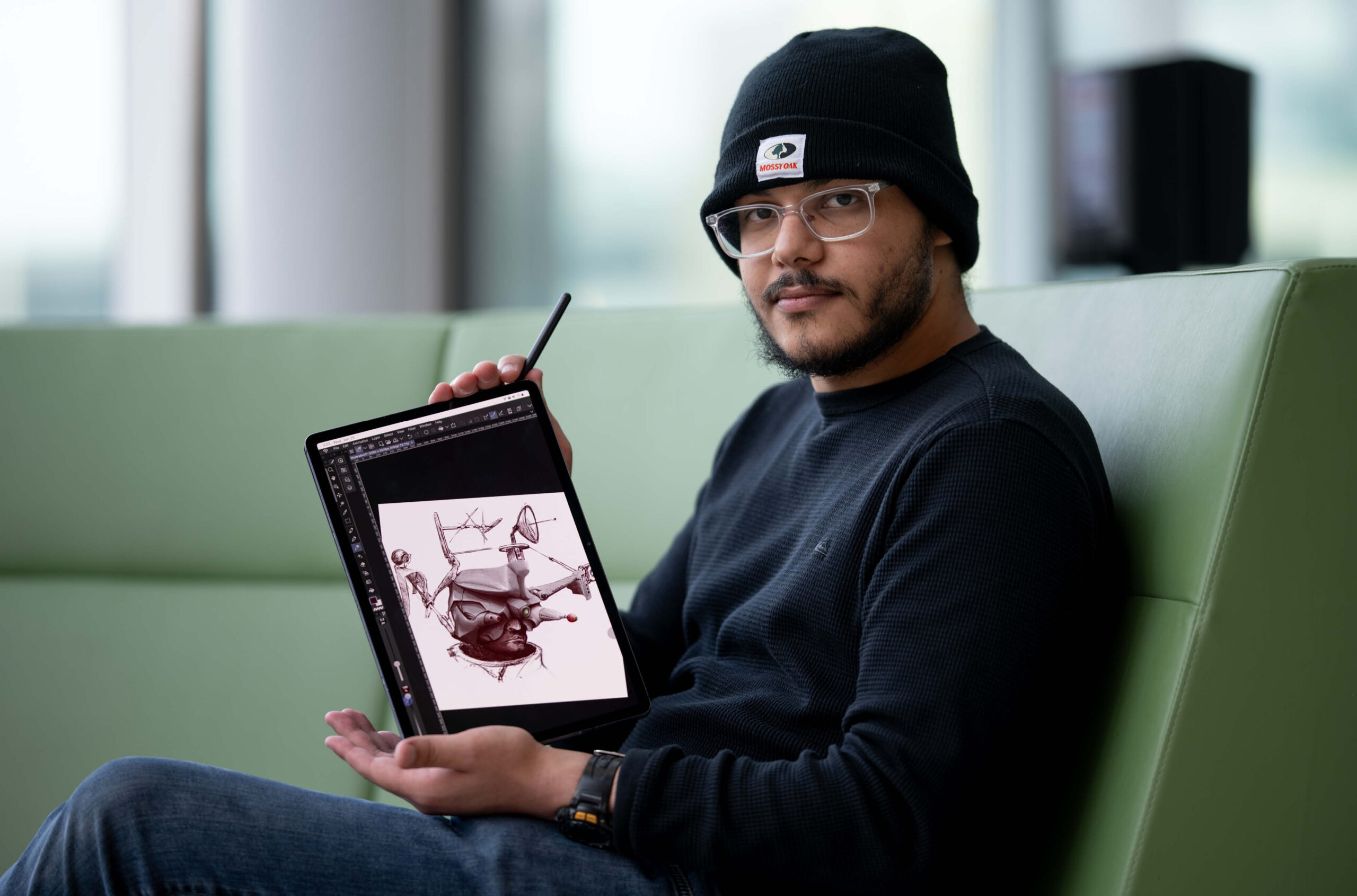

Shree Mulay says she’s noticed a change in attitude when it comes to the selection process for Canada Research Chair appointments at Memorial University, where she’s a professor of community health and humanities. Compared to years past, more attention is paid to hiring candidates from diverse backgrounds.

A similar shift has been taking place at universities across the country, due in large part to a legal saga spanning nearly two decades, spearheaded by a small group of women professors including Dr. Mulay.

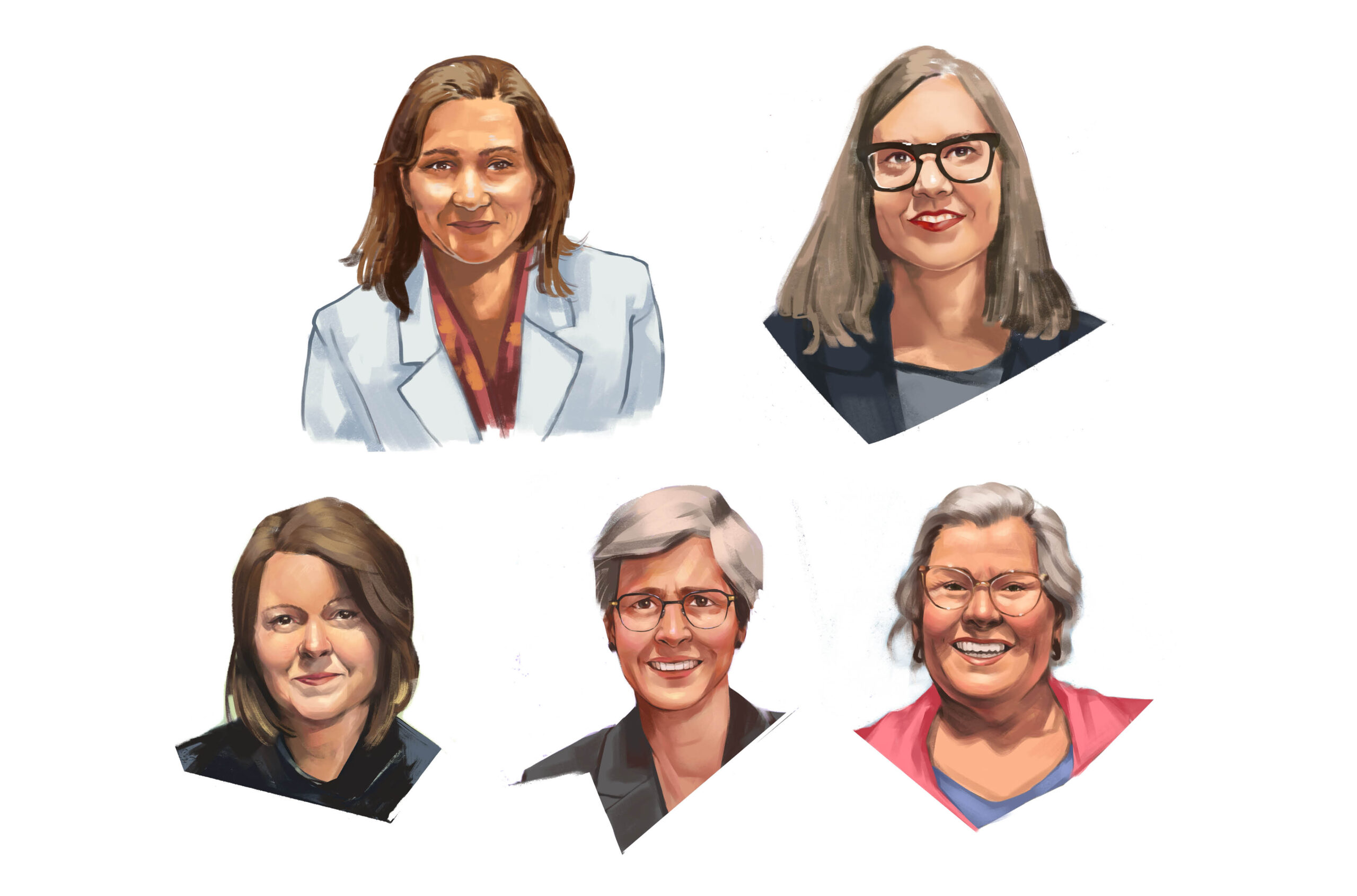

Back in 2003, she and Marjorie Griffin Cohen, Louise Forsyth, Glenis Joyce, Audrey Kobayashi, Susan Prentice, Wendy Robbins and Michèle Ollivier filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission. They argued that the CRC program was discriminating against people belonging to protected groups as defined by the Canadian Human Rights Act, resulting in an overrepresentation of white men in these coveted chair appointments.

The program had been set up three years earlier to fight “brain drain” among the country’s top academics. The government’s position at the time “was that Canada Research Chairs were really meant for people who are outstanding, so equity does not really come into the picture,” Dr. Mulay recalls. “Our position was, and is, that excellence doesn’t need to be at the expense of equity – that it is possible to achieve both.”

Their efforts led to a 2006 settlement under which the federal government agreed to create a panel that would set targets for four groups – women, people with disabilities, Indigenous peoples and visible minorities – based on the pool of available candidates. Then in 2017, the settlement became a federal court order after the complainants argued there had been too little progress to deal with underrepresentation. A mediation process ensued, and Ottawa agreed in 2019 to set new targets based on the population at large, and enforce them.

As Dr. Mulay puts it, “what was quite obvious is that if we were to use only how many people in different categories were there in the academy, we would actually never reach equity.”

While both agreements are legally binding, a separate human rights complaint by University of Ottawa law professor Amir Attaran in 2016 led to another settlement. Issued in March of this year, that agreement added teeth to the enforcement. If participating postsecondary institutions don’t meet their targets by the end of 2029, the number of research chairs they receive will be cut. Universities were also required to finalize “action plans” by May 28 of this year, outlining how they would meet their targets for their nominations to move ahead.

Today, the program funds 2,285 positions at 76 universities, dispensing nearly $300 million annually. Tier one chairs receive $200,000 in funding annually for a seven-year term while tier two chairs are appointed to five-year terms and receive $100,000 annually. Both are renewable once.

As of March, 38.6 per cent of the chairholders self-identified as women, 21.4 per cent as visible minorities, 5.5 per cent as people with disabilities and 3.2 per cent as Indigenous. By comparison, the 2029 targets are 50.9 per cent for women, 22 per cent for visible minorities, 7.5 per cent for people with disabilities, and 4.9 per cent for members of Indigenous groups.

The program is administered by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Its vice president, Dominique Bérubé, says the entire process has had a broad and lasting impact.

“We will always acknowledge the work of those initial complainants, the time they dedicated to transform the program,” she says. “It’s now transforming the research ecosystem.”

Dr. Bérubé says success rates – the proportion of applications submitted by universities that are approved by SSHRC – have risen as institutions have inched closer to the targets. That runs counter to any notion that there was a dearth of qualified candidates from diverse backgrounds. All universities that are required to have submitted action plans, but a few have yet to be approved by the agency.

There is still a lot of work to do over the next few years, Dr. Bérubé says. “The 2019 agreement addendum had more than 65 measures in it. So we’ve got plenty more engagement to do to onboard all of them – whether it’s about disaggregating data, the LGBTQ community, or introducing an intersectional approach.”

Sara-Jane Finlay, associate vice-president, equity & inclusion at the University of British Columbia, says one of the biggest challenges is appointing faculty with disabilities, and that’s reflected in the targets. While around 15 per cent of Canadians are believed to have some form of disability, she says, the settlement set a target of only 7.5 per cent.

“The barriers to hiring faculty who indicate that they have a disability are much higher than for many others. And I think that’s partially because of our lack of understanding around disability and around accommodation. I think it’s also about the narrow confines of a tenure path,” she says. “And that may not make the space for faculty who have disabilities and may have time off work or may require accommodation that means they’re working part time.”

Another issue has to do with inclusion. “We need to be giving more thought, not just to representational diversity, but to the environments that we’re bringing faculty into,” Dr. Finlay says. “The CRC program deals with representational diversity but it’s not dealing with the other side of it, which is the inclusive environment.”

For her part, Dr. Mulay, sees the human rights settlement that she and her co-complainants fought so long for as “a small part of the total picture.”

“The larger issue, as far as I’m concerned, within universities is the part-time, sessional faculty members who are hired, because those positions are still filled by people who are women, who are visible minorities and so on,” she says. “If one is going to look to the future, then those are the kinds of inequities that need to be addressed.”

Featured Jobs

- Human Resources and Organizational Behaviour - Lecturer, 2-year termUniversity of Saskatchewan

- Creative and Cultural Industries - Assistant Professor (Fashion Studies and Cultures)Chapman University

- Architecture - Assistant ProfessorMcGill University

- Research Chair in Systems Transformation and Family Justice (Faculty Position)University of Calgary

- University LibrarianYukon University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

“Dr. Bérubé says success rates – the proportion of applications submitted by universities that are approved by SSHRC – have risen as institutions have inched closer to the targets. That runs counter to any notion that there was a dearth of qualified candidates”

1. No it doesnt. Being approved = being qualified does not address the question of excellence.

2 “resulting in an overrepresentation of white men in these coveted chair appointments” the representation = equity argument is specious. nursing and education would be extremely discriminatory against men if Berubes logic is followed. I doubt anything will be done about that.

3. the brain drain will continue if race and gender becomes a necessary factor in selection. there are more men than women in the bottom and top 1% of performance distributions.

4.”While around 15 per cent of Canadians are believed to have some form of disability, she says, the settlement set a target of only 7.5 per cent.” the dialectic never ends and there will never be the equity Mulay et al idealize.