A “stepped” approach can help to ease access to mental health care on campus

A Q&A with Peter Cornish of Memorial University on the Stepped Care model, which he hopes will get everyone on campus to be part of the support system for those dealing with mental health issues.

In 2014, Peter Cornish helped the Student Wellness and Counselling Centre at Memorial University launch the Stepped Care program. With this model, the level of intensity of care is matched to the complexity of the condition. When someone says they are stressed, or they are not feeling happy, then society tends to say, “Okay, go see a psychologist,” said Dr. Cornish, who is director of the counselling centre. However, not everyone needs to see a therapist all of the time. The Stepped Care model brings in many other “low intensity” options for the patient that are readily available in the community, but which we’re often not making use of. University Affairs sat down with Dr. Cornish to find out more about the Stepped Care model and why universities should consider it.

In 2014, Peter Cornish helped the Student Wellness and Counselling Centre at Memorial University launch the Stepped Care program. With this model, the level of intensity of care is matched to the complexity of the condition. When someone says they are stressed, or they are not feeling happy, then society tends to say, “Okay, go see a psychologist,” said Dr. Cornish, who is director of the counselling centre. However, not everyone needs to see a therapist all of the time. The Stepped Care model brings in many other “low intensity” options for the patient that are readily available in the community, but which we’re often not making use of. University Affairs sat down with Dr. Cornish to find out more about the Stepped Care model and why universities should consider it.

University Affairs: You mentioned that there seems to be a view in the media that we are in the midst of a mental health crisis, but you said it is actually more of a crisis of access. What is the difference?

Peter Cornish: This is a controversial question. Some of my colleagues in the field would argue that there is a change in population in terms of resilience, that people are feeling more distressed and needing services more than before. I don’t argue with that. However, there aren’t more mentally ill people. People are not sicker than they used to be. What’s happened is that because people want more support to make their lives better and are feeling stressed, is there’s a lot more demand for support. So, the crisis of access can be broken down in two ways: we have limited types of programs available and they tend to be designed for people who are psychiatrically ill. And we have almost nothing for people who aren’t psychiatrically ill, but are looking for supports. So everyone lines up whether they are ill or not, for a psychiatrist or a psychologist. And the access issue is that we’re sending everyone to high-intensity supports whether they need it or not.

UA: Why do you feel this shift has happened?

PC: I think, because of human rights legislation, we all think much more about accommodating people who otherwise would not be given a chance in the education system or the job sector. But there is also a fear factor that has come in, when we see mental illness, we wonder: “Uh oh, is this person going to blow?” And so the fear factor then leads us to say: “Well, maybe I shouldn’t talk to this person, shouldn’t offer support. Maybe they are dangerous and maybe I won’t be good enough as an average citizen to help, so I am going to feel anxious and I’m going to call up the professional and pass the ‘hot potato’ to them.” Ideally, we would have an access system that allows us to try to be just human, with anyone, until we discover that’s not enough, and then we involve the professional.

UA: I think there’s a fear, too, that we’ll say the wrong thing.

PC: There is a fear of failure. What I say when I am training in this [Stepped Care] model is that failure is not bad, as long as it’s managed. Life is trial and error. Let’s be nice and see how that works. And if or when that fails, don’t just send [the patient] to a psychologist. Maybe, get on the phone with someone who can actually give you a bit of advice, so that you’re not passing the “hot potato” even after the first failure. You might get a little advice on how to support that person. If that fails, then go to the professionals. That’s kind of the thinking that we’re trying to encourage.

UA: Do you feel those in your profession are coming around to this way of thinking?

PC: What I find is 70 percent of mental health professionals say this is great, and 30 percent say, “Hmm, I am not quite sure I know how this is going to work.” Or, “I am not trained in this different way of thinking.” And so they are understandably skeptical. But the users – patients – all say, yes, this makes complete sense. University administrators also say it makes perfect sense, because some universities have responded to the crisis by just adding more counselors, and it doesn’t make a difference. You can add more specialists, but I think it actually makes things worse. Because it is encouraging this idea that we should marginalize anyone that is struggling by professionalizing and medicalizing them and sending them for treatment, as opposed to saying: I think we can all be part of the solution.

UA: Can you give an overview of the Stepped Care program?

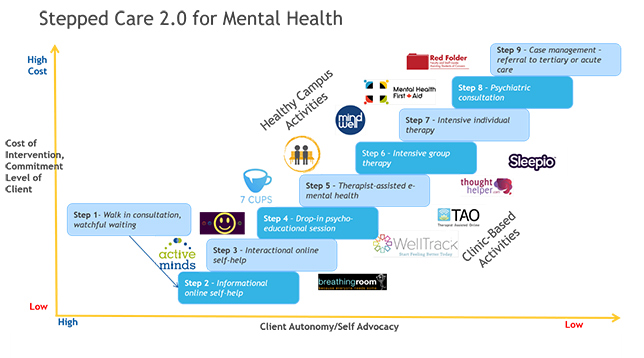

PC: This program first started in the U.K. about 20 years ago and was talked about in the context of primary care health, where the physician is the main point of contact that then sends patients out to a specialist. The U.K. National Health System decided they were going to try different options with patients, based on level of severity of distress. You can think of it in terms of medication: you start with a lower dose and you only increase to a higher dose when necessary.

The U.K. system only had a few steps in it, and was fairly rigid and rule-based. The version that we’ve come up with at Memorial is much more flexible, but still evaluates changes in outcome at every point of contact, using good, solid assessment tools. We want to maximize the involvement of the patient in the decision-making process so that in the end, unless they are incapable of making decisions, they are taking responsibility for their health.

When I first meet with someone, they see – graphically – the model that I am talking about. So if they look at the model and they don’t like what they see, we will ask them if there is something missing that would work for them. What level of intensity do they want? And by intensity I mean, do you need someone right now to challenge you? If you think of it in terms of the academic part of a student’s life, are they ready for a hard course? Or do they want an easy course?

There’s an assumption that therapy is meant to be all supportive and easy. You go to a therapist and they’ll be nice to you and you’ll go away feeling better. In fact, it works better when people are ready for a bit of struggle. But, because there’s no lower intensity options built into most of our health care system, and we have to take everyone, what ends up happening without Stepped Care is that therapists have to be really gentle and you have to wait a long time to see one.

With our model, we start the relationship right away. If the patient is not ready for a challenge, I’m still going to meet with them, but I won’t spend an hour with them every week, trying to do therapy. I might meet with you very briefly and then get you to do some reading. Often when people aren’t ready, they need information to make a decision about whether they want to embark on something that’s hard. And then, sometimes what we find is that those little interventions actually are all they need right now. They get something out of it and they are good to go. But they also know that, now that they have connected with me, they can always come back if they want to take another step later.

UA: What are some of these low-intensity options?

PC: The first step is to meet with the patient. The next step I would put in a category of education or mental health literacy. There are apps that have info, and of course there’s the library and Google. We coach them on how to be discerning and what info you can trust. And then they can come back and talk about it. It’s a similar process to what students would do with a professor during office hours. We are still counsellors, but we are actually saying: “We don’t have to do therapy; we will just be the prof for a moment.” And that de-stigmatizes it. You’re not in treatment, you are just consulting, and I am an expert, and you go off and read and I will tell you whether you got it right.

Step three gets the patient to do a little bit of work: reading books and using workbooks or online mental-health tools that have workbooks built in. For example, we might have them do a seven-module treatment, or program on anxiety, stress or depression. At that level, the patient is interactive with the program, but doesn’t have a therapist or a coach formally involved. They might drop in and tell us how it went, or we might not ever see them again – they go off and use that and they are fine.

Step four is educational, but has therapists involved. For example, workshops or one-time kinds of things like classes on particular topics. At this level we also include peer support programs where people can consult with other students on campus.

UA: What happens next if that still isn’t enough?

PC: The next level up is what I call counsellor or therapist-assisted mental health, where the therapists act a bit as coaches, with the addition of online content. So this is equivalent to a flipped classroom concept in education where the course material is online and students will review this on their own time. But then they also have a chance to come in, interact with the expert, or instructor, or their classmates to work through particular assignments and problems, so that then the so-called office hours are actually a central part of the learning, where they come in and they do it as a lab; they work on things together. This is actually one of the more exciting levels in terms of outcomes, because we are getting good data coming in where patients are spending a quarter of the time a week with counsellors compared to traditional counselling. Because the content and the workbooks are available 24/7, patients are actually spending more time working on issues, but do so independently. The outcomes are in most cases, much better, and at minimum they are at least as good as when a counsellor spends an hour per week with them. So you’re getting more with less.

And then above that are traditional interventions of different intensity. Even in those traditional areas, we are experimenting, doing it a bit differently and using time differently. We’re not necessarily always doing an hour; sometimes 30 minutes is enough. With the psychiatric services in a Stepped Care model, the psychiatrist doesn’t necessarily do all the work, they work with a physician. They don’t do it in isolation; they provide expertise to the physician.

We are actually building a dashboard so that everyone involved in the care, especially the patients, can see which level of intensity resources they are using, with the motivation always being for them to manage their health themselves – to be empowered, to be as independent as they can. And, built into that dashboard is a feedback mechanism, like what you would get on a FitBit, of how well you are doing with managing your own health, and being able to see the outcomes, the resources that you are using, and then see which ones are working best.

UA: You mentioned earlier that staff and faculty sometimes feel unprepared to provide informal support. How will the model address this?

PC: Currently we are expanding the model to organize, along a stepped model continuum, health promotion and illness prevention activities aimed at the whole campus population. This will ensure that care and support systems are more fully integrated throughout campus communities with the goals of maximizing efficiencies, collaboration and stakeholder – by this I mean student, staff and faculty – empowerment. All members of the community will be supported through engaging and creative campaigns as well as some training programs to participate in the development of a healthy campus.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Featured Jobs

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

3 Comments

I’d like to share a resource that acts as a navigation tool for post-secondary students and for the health services department at the college/university. It’s called myWellness. It’s built with these two functions in mind:

1. Supporting the student by increasing awareness, giving them self-guided tools, access to an evidence-based, anonymous assessment with DMS-5 criteria, and finally leading them to the appropriate care on campus, in the community, or online.

2. To assist the health services team on campus as a triage tool, allowing them to priority the severity and nature of the mental illness, and enables the care member to use the assessment tool as a spring board for discussion with the student and a possible treatment plan.

I know that over a dozen post-secondary institutions in Canada use this tool and have a high utilization rate among students and staff. I encourage you to check it out, as it does correlate very closely to this stepped model. Instead of having a bottle neck at the counselling department, why not filter and schedule students to the appropriate care and in the time that reflects their actual need.

Here is the website to the tool: http://www.mywellnessplan.ca or you can contact in**@my************.ca

Focus on mental health in universities seems to always be on students. I am currently a faculty member seeing both a psychologist and psychiatrist, and both of them say that a great number of their clients are academics.

A lot more needs to be done to help faculty, not just students, in university.

I like this idea of a stepped approach, and often faculty are the front line dealing with student issues, so a starting point website that helps them with online resources would be really useful. As faculty of course we’re not trained to be their therapists, and yet often they come to us first. Please get useful resources out to faculty. Sending a student to the counselling centre is often off-puttting for the student, who thinks they don’t need counselling, just an adult to listen and offer advice.