The unloved Canadian Common CV is in for an overhaul

The Tri-Council funding agencies have announced that a redesign of the CCV is underway.

The Canadian Common CV, or CCV for short, sounds simple enough: it’s a standardized tool that researchers use to upload their curriculum vitae for major funding applications. But after 15 years, the anything-but-simple CCV seems slated for a massive transformation, if not a death knell.

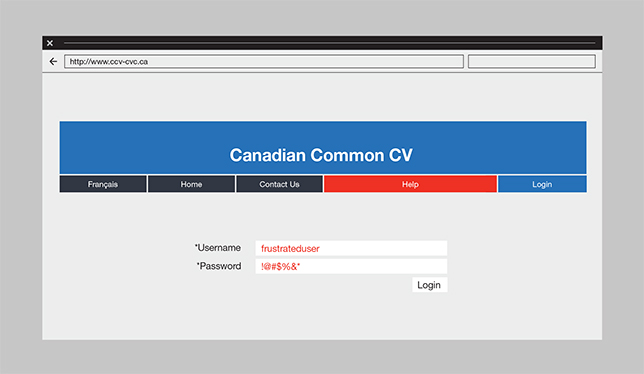

When the program was launched in 2002, it was heralded as a way to make researchers’ lives easier – they could use the same common CV regardless of the funding competition. But the online tool has been buggy and cumbersome. Researchers’ frustrations with it have been aired in passionate blog posts and tweets. “It’s been pretty amazing, it consistently underachieves,” said Jim Woodgett, director of research for the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

Even Canada’s 2017 Fundamental Science Review panel, headed by former University of Toronto president David Naylor, took notice. In its report, the panel lambasted the CCV for its “complex and user-unfriendly web interface,” frequent crashes and “rigid architecture that precludes freeform entries.”

In July, the Tri-Council funding agencies responsible for the CCV – the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council – announced that “a redesign of the Canadian Common CV is underway.” (In the meantime, the CCV is still being used for competitions.)

But, according to Adrian Mota, acting vice-president of competition management at CIHR, the Tri-Agency governing board is considering starting from scratch. In consultations over the next few months, according to Mr. Mota, funding stakeholders will be asking: “How much can we harmonize? Does it make sense to harmonize? Is it CCV 2.0? Or is it something different?”

On that last question, Mr. Mota said the consultations will explore whether the CCV could be replaced by existing third-party tools that import researchers’ professional histories, such as the PubMed or ORCID platforms. Given that the possibilities are so open, Mr. Mota couldn’t say when a new or different CV application might be up and running.

In addition to the three major funders, the CCV secretariat will consult with the 24 other agencies that use the CCV, including the Canadian Council for the Arts and the Canada Foundation for Innovation, as well as researchers and research administrators.

One of the biggest issues with the CCV became apparent within a year of its launch, recalled Dr. Woodgett. “Every time there was a grant deadline, the darn system would crash because of all of the editing going on by thousands of researchers,” he said. The crashing problem improved over the years, but other issues emerged, like cryptic error messages that would occur when researchers tried to use the same CV for two different competitions.

“Each competition has different requirements, so when you apply for a new competition, suddenly your CCV is populated full of red error Xs,” said Holly Witteman, an associate professor in the department of family and emergency medicine at Université Laval. “It just takes away the whole idea of ‘common.’”

Updating the CCV – whether to meet the requirements of a new competition or to add recent works – can be painstaking. For a journal article, for instance, the volume, page numbers and so on are all separate fields. When the CCV website was particularly slow, it could take “30 seconds to a minute” to update a single page number, according to Bruce Allen, a research professor at the Montreal Heart Institute. When he had to create a CCV for a grant a few years ago, the process took “it seemed like a couple of weeks,” he said.

The program has been so onerous that several universities have bought third-party software, called CCV Sync, that simplifies the CCV updating program. Diego Macrini, CEO of Proximify, the software company behind CCV Sync, said he thinks the problem with the CCV is that it was designed for the needs of the agencies, not the research end-users. “From a software perspective, you always beta test with people who will be using the software. That never happened,” he said.

Dr. Woodgett said he worries that pattern will continue. “We’ve heard from the agencies that there is a new version coming along but there’s been no request for input,” he said.

Mr. Mota acknowledged that beta testing didn’t occur with the last extensive redesign of the CCV in 2012. “The application was incredibly slow and buggy, and people really struggled with the user interface. Could that have been avoided? My sense is that we could have done better,” he said, though he wasn’t directly involved with the CCV redesign at the time.

This time around, Mr. Mota said, there is a “comprehensive consultation plan” that is being implemented over the next few months. Once a program has been created, months or years down the line, “our goal is to eventually have beta testing of users,” he said.

“We’re very much supportive of what the [Naylor report] said and we agree the CCV needs to improve,” Mr. Mota added. He stressed that this next round of consultations won’t result in a 2012-like redesign. “We’re not just going to put Band-Aids on the existing application. We need to agree on what the vision is and I think we have a pretty clear path based on years of user feedback.”

Featured Jobs

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

9 Comments

Kill the CCV. Return to the simple and intuitive approach formally used by NSERC for Discovery grants and still used by SSHRC for standard research grants. Those formats are easy to create and update because they use standard word processing and they are easy for reviewers to follow. The CCV can use 50+ pages for information that will fit into 4 in the old format. This is particularly problematic since most reviewing of grants is now done on screens. All that scrolling adds a huge amount of extra wasted time to the reviewing process. I experienced this as an NSERC Discovery grant committee member; one year with the old CV format (easy, fast, simple, familiar) and one year with the CCV (hard, slow, complex, unfamiliar). It added hours and hours to the reviewing process. In summary, the old CV formats worked well. No special software required. All researchers already have the information needed – cutting and pasting into a Word document takes very little time whereas adding the information one piece at a time into a form (no cutting and pasting available) is slow. Consult the users! Do not waste time and energy solving non-existent problems.

What Jo-Anne said! The ideals of Common CV were perhaps initially noble but were defeated in implementation and through committee-based design. This sorry sack of rotten potatoes needs consignment to the garbage bin (when it can join the remnants of the CIHR reforms).

It’s important to understand that people have already invested significant effort in the last 5 years entering their CV data into the CCV. So, throwing that away and staring with a different system doesn’t sound like a reasonable option.

The current thinking by the Tri-Council is that the CCV problem should be consider within the larger problem of funding applications, where there are other kinds of inefficiencies. Last night I posted my opinion on how that could be done in a way that doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the past.

https://medium.com/@macrini/how-to-streamline-research-funding-applications-in-canada-6ffe68ae57b

I’m understand the argument on CCV over compliance. But the solution of having CV templates works well when is properly implemented. We have shown that that is the case. So it’s possible to have the simplest of CV requirements within a more compliant CV format that allows for effective data reuse in the institutions’ annual activity reports.

You wouldn’t care about over compliance if the information that you type in was used for both institutional reporting and funding applications. As long as you have to enter data only once into ANY system, then the question becomes what’s the most efficient UI (and import options) to enter the data.

Add an “Export” button to CCV? And an “Import from CCV v1” button to CCV v2 ?

Agencies are thinking about CCV 3.0 because the CCV of today is 2.0. There was a 1.0 that mostly people in Quebec used prior to 2012.

The agencies have a predilection for grand redesigns based on long assessment phases in which the needs of all 30+ agencies are considered. At the end of that phase, they will ask some hand picked researchers with no expertise in research information systems what they think. All this already happened with 2.0.

In the mean time, they are hiring new ppl to get large IT teams ready for the big enterprise ahead. When ready, they will embark in building the solution to all problems. As you can probably guess, this will likely lead to a whole range of new problems. I just hope to be wrong because I want them to succeed.

The CCV problem of today can be solved in exactly two weeks, and we have explained to them how to do this since 2014. We already built a system that does 100% of what CCV does, and is 100% compatible with all the data already stored in it. So they can adopt our system and make it free for everyone. It’s Canadian made, bilingual, built by researchers, and liked by researchers and institutions.

Another solution is the CRA model, in which the government only makes the backend, and private companies sell frontend software (eg, TurboTax, UFile). A hybrid is also possible, where the government makes one free frontend as well.

And to answer the comment, we already have import/export functionality. And going from 2.0 to 3.0 should not require changing the underlying data schema, so import/export should stay the same. In the software industry, the norm is to improve one thing at a time. So, task number one should be fixing the UI, which is trivial because that is already done. Task number two should be to look into how to improve the data schema in order to benefit both the agencies and the institutions. If the CCV is not about helping the institutions reuse CCV data for activity reports, then the CCV 3.0 will still lead to massive wasted time due to administrative duplication.

For many researchers, CCV was never an issue because they did all the work in UNIWeb’s UI, which is always supper fast and no on deadlines.

That demonstrates without a doubt that the problem with the CCV was the UI, and that for 5 years, over 10K researchers have been happy with at least one alternate UI for it.

For example, this is recent feedback from an institution that has been using the software since 2013.

Biosketch….it is actually that simple.

https://cmajblogs.com/the-canadian-common-cv-an-academic-pursuit-of-hyper-compliance/

Diego, I would suggest that, if surveyed, a large proportion of Canadian researchers and nearly all international collaborators, would have absolutely no problem getting rid of the CCV – even after all the time committed to entering information/details (and countless $$ wasted). In fact, it would actually reflect that someone is listening. I personally would take great pleasure in knowing I never again have to click on CCV dropbox….

The only thing that makes sense at this stage is the CCV homepage linking to NIH’s biosketch instructions.

I can actually tell you, with great degree of certainty, that there are thousands of Canadian researchers that would not be happy at all if the CCV disappears. That’s because: 1) They never really used the CCV website to enter data for funding competitions (i.e., they used UNIWeb); 2) They generate their departamental annual activity reports from the same data pool that they use for the CCV. So, if the CCV dies, they will again have to worry about maintaining at least two different academic CVs. A very backwards notion indeed.

You can read about how this is done at uOttawa and UBC Okanagan here: https://uniweb.network/clients/Proximify/uniweb/published/docs/UNIWeb_2017_sm.pdf

Those institutions and others have been doing this for many years now. We made that solution available to every single Canadian institution since 2013. And we built the solution because in 2012 our colleagues asked us if we could, and because we are researchers too!

I forgot to add that making an input templates that looks identical to NIH’s biosketch would take us just two days. So, we can make your wish come true while also letting other scientist reuse more data for annual activity reports.

We have already done this. We have created input templates for different needs in different institutions. In fact, we have even done it for different departments in the same institution.

And we solved disagreements about citations styles by making that a user-level choice.

In other words, if the challenge is health related, I would follow your advice. But for this, you are better off following mine. I mean this in a respectful way. We have shown in practice that we know what we are saying because we already built it.