The 10,000 PhDs Project: a closer look at the numbers

This snapshot of employment outcomes confirms that, regardless of their discipline, U of T PhDs are successful in a wide range of careers.

When Nicholas Dion graduated from the University of Toronto in 2012 with his PhD in religion, he made a surprising career move – he turned down two academic positions and accepted a paid internship as a researcher with the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, or HEQCO, a policy think-tank and advisory body to the Government of Ontario. In part, this decision was due to the uncertainty of the academic job market. Tenure-stream positions were in rare supply and the prospect of seemingly endless contract faculty positions was not appealing.

But are career moves like Nicholas’ really that unconventional? One of the key issues facing universities, departments and their PhD students is the lack of high-quality employment outcome data. Where exactly do PhD graduates in the new millennium find employment?

The 10,000 PhDs Project, an initiative of the school of graduate studies at U of T to improve the graduate experience, used Internet searches of open-access data sources such as university, government and company websites to determine the current employment status (as of 2016) of the 10,886 PhDs who graduated from U of T from 2000 to 2015 in all disciplines. A similar methodology was used by HEQCO in their study of 2009 PhD graduates from Ontario universities. The U of T study successfully located 85 percent of PhD graduates. Cross-checking departmental data records with publicly available website information located a further three percent, bringing the total percentage of found PhD graduates to 88 percent.

Increase in U of T PhD graduates

In 2005, the Government of Ontario provided additional funding to universities to increase graduate enrolment by some 14,000 spaces and again in 2011 by 6,000 additional spaces. This increase in funding resulted in PhD enrolment in Ontario universities doubling from approximately 10,000 in 2000 to 20,000 by 2013. Enrolment expansion was driven by certain imperatives: the double cohort of undergraduates (in 2003, Ontario eliminated Grade 13 and therefore doubled the number of students who would graduate starting in 2007); baby-boom faculty retirements (projected to cause a faculty shortage); and the perceived need for highly qualified personnel to drive economic innovation.

The number of U of T PhD graduates increased 1.8-fold from 494 in 2000 to 901 in 2015 (Figure 1). The largest increase was in physical sciences (2.6-fold), followed by life sciences (2.2-fold) and then social sciences (1.4-fold). The number of humanities graduates remained constant at about 100 for each year from 2000 to 2015. U of T attracts a diverse set of graduate students from Canada, the U.S. and around the world. Together, international students and permanent residents comprised approximately one-third of PhD graduates during the study period.

PhD graduates find jobs in a variety of sectors

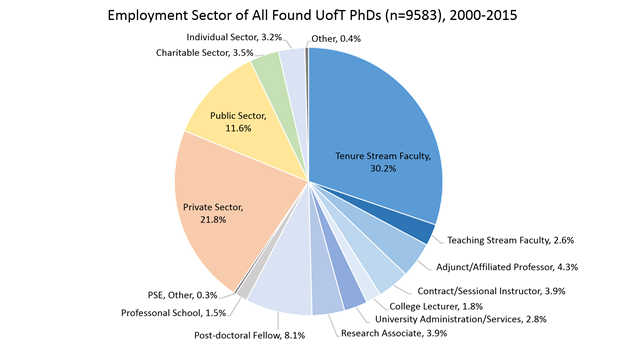

Figure 2 shows that PhD graduates are currently employed in a variety of sectors. Nearly 60 percent of the 2000-2015 PhD graduates who were located are employed in the postsecondary education sector, 22 percent in the private sector, 12 percent in the public sector, three percent in the charitable sector, and three percent in the individual sector.

Just over 30 percent of PhD graduates from 2000 to 2015 currently hold tenure-stream faculty positions within the PSE sector. This percentage varies with graduate division, the highest value being in the humanities and social sciences (42 percent and 41 percent respectively), followed by physical sciences (26 percent) and then life sciences graduates (21 percent). Graduates also found employment as college lecturers (1.8 percent) and as contract/sessional instructors (3.9 percent), most commonly in the humanities and social sciences. Others work in the PSE sector as full-time research associates (3.9 percent) or in university administration (2.8 percent). Eight percent of all found PhDs, mostly recent graduates (2011-15), are continuing their training as postdoctoral fellows. Other recent graduates (1.5 percent) are in professional schools (medical, dental, law, etc.).

U of T graduated about an equal number of female (49 percent) and male PhDs (51 percent) from 2000 to 2015. The percentage of female PhD graduates varied by division: 24 percent in physical sciences, 55 percent in humanities, 56 percent in life sciences and 65 percent in social sciences. Forty-six percent of those currently employed as tenure-stream faculty are female, while 54 percent are male.

Areas of employment in the private sector

Increasingly, PhD graduates, particularly in the physical and life sciences, are finding employment in the private sector, often in leadership positions, contributing to an innovation economy. The percentage of PhD graduates employed in the private sector was highest in the physical (40 percent) and life sciences (21 percent). In the physical sciences, major employers are in engineering (27 percent), information technology (17 percent), and finance (13 percent). In life sciences, major employers are in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors (59 percent).

Where in the world are U of T PhD graduates employed?

We were also able to determine the current employment locations of 9,583 graduates. The data suggest that there is a net “brain gain” for Canada. Seventy-five percent of Canadian citizens and a combined total of 46 percent of permanent resident and international PhDs are employed in Canada. Canadian citizens are also employed in the U.S. (17 percent) and outside North America (eight percent), often as postdoctoral fellows. The project also tracked the locations of international students who found employment outside Canada. Further findings showed that the majority (68 percent) of Americans found employment in the U.S. A similar percentage (67 percent) of Japanese citizens returned to Japan. Twenty-four percent of Chinese citizens remained in Canada; 21 percent returned to China and 24 percent went to the U.S. Forty-five percent of postdoctoral fellows are employed in Canada, 35 percent in the U.S. and 21 percent internationally.

PhD graduates are employed as tenure-stream faculty at 64 different Canadian universities, contributing to the academic workforce across the country. The top three universities for U of T PhD graduates who are currently employed as tenure-stream faculty in Canada are U of T, York University and Ryerson University, indicating a strong local geographic preference. Nearly 80 percent of the U of T PhD graduates who are employed as tenure-stream faculty by Canadian universities are Canadian, 16 percent permanent residents and four percent international. U of T graduates also found employment as tenure-stream faculty in the U.S. and internationally in top-ranked (QS Ranking), research-intensive universities like Harvard, Stanford, University College London, Imperial College, University of Chicago, etc. After the U.S., tenure-stream positions in universities in China and Asia dominated, with Australia and Middle Eastern countries also well represented.

Transforming graduate education

The snapshot of employment outcomes provided by the 10,000 PhDs Project confirms that, regardless of their discipline, U of T PhDs are successful in a wide range of careers, from academia to industry, the public sector and beyond. Sharing such data has many benefits. It can encourage graduate administrators and faculty to assess how well academic programs and professional development programs are preparing students for their futures. Crucially, it can also help prospective and current students gain greater knowledge of the diversity of employment outcomes available to them. For this reason, U of T is providing access to these data through a dynamic dashboard on the graduate school website. Surveys and interviews with alumni will also be carried out to learn more about individual career trajectories and to communicate these widely.

As Brandon Ho, a PhD student in Biochemistry at U of T, stated: “There are misconceptions concerning postgraduate school. I think having results from the 10,000 PhDs Project will give current students a clearer idea of what to expect after their graduate career and will be a beneficial resource in helping prospective students in their decision-making process.”

Reinhart Reithmeier is a professor in the department of biochemistry at the University of Toronto and was special adviser to the dean of the school of graduate studies from 2015 to 2017.

This article is a summary of a 10,000 PhDs Project Report submitted by the author to Joshua Barker, dean, school of graduate studies and vice-provost, graduate research and education at the University of Toronto. The author and team members wish to thank Locke Rowe, former dean of the graduate school (2014-2017), for his support of this initiative and Linda Jonkers from HEQCO for advice on data collection. This research project was carried out by: Reinhart Reithmeier, project leader; Liam O’Leary, research co-ordinator; Corey Dales, IT Support and data integrity; Abokor Abdulkarim, Lochin Brouillard, Samantha Chang, Samantha Miller, Wenyangzi (Ann) Shi, Nancy Vu, Xiaoyue (Grace) Zhu and Chang Zou, research assistants, with financial support provided by the school of graduate studies.

Featured Jobs

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

15 Comments

One note about the piechart is that the 8.1% of postdoctoral fellows will eventually become academics or industry researchers in the future, as most fellowships last 3-6 years and the 8.1% are most likely the 2015 graduates. Overall, such rich data will surely help transform the ways in which faculty members think about mentorship and enhance graduate curriculum with professional development. A PhD education is not only about achieving excellence in disciplinary research, but also maturing into a “whole” thought leader, to contribute to research, development, policies, and societal outreach for Canadian and global academia, innovation and economy.

In light of the data that shows many graduates, especially in the physical sciences, choose a career path in the private sector, I hope the report will make some university administrators think about how they prepare their PhD’s for life after school. It is my sense that PhD students receive very little training or career advise for non-academic careers.

the biochemistry department at U. of T (where Reinhart is originally from) has an incredible, comprehensive graduate training program to prepare students for a range of careers outside of academia. it is slowly spreading to other departments within and outside of the faculty of medicine. physical sciences grad coordinators should check it out. it was written up recently in University Affairs.

Congratulations Reinhart and team, and the University of Toronto, for launching this seminal study. It signals a transition in “accounting” of the impact of graduate education; ie, more towards what we’d like to know – are graduates pursuing careers that they love, while impacting society? It will be great to see how some of these numbers compare to other major academic centers in the US and EU, and, of course, to start to read and experience some of the faces and stories behind the 10,000 data points. Ultimately it is these stories that will inspire would-be and current graduate students, and give them some confidence that there are limitless possibilities for a graduate-level trainee from U of Toronto. Well done, all.

The results of the 10,000 PhDs project is a great resource for students to help guide their post-PhD careers and shape their graduate training accordingly. As a PhD student at UofT, it is great to see the diverse employability of UofT PhD graduates. I was surprised to find that almost 60% of graduates work in the PSE field, and the rest in very diverse fields. The breakdown based on disciplines is quite interesting and I think departments should look at it and offer appropriate training to their students. Looking at just the sciences, there is a great opportunity for life sciences students to go into the private sector (in absolute numbers, life sciences students make up most of the graduating PhDs but represent a lower percentage of workforce in the private sector compared o physical sciences). Schools, governments and students should look at this data to figure out how to take advantage of the brain power developed in graduate programs towards stimulating the life sciences industry in Canada.

What a great resource the 10,000 PhDs Project will be for students looking to explore the possibilities of employment beyond the PhD! This would also be useful for educational institutions and policymakers alike, in determining what resources to provide and guide graduates-to-be. I’ve shared this with my peers in my graduate department, and I believe it will be very helpful to clarify the often nebulous idea of what one can do after graduating with a PhD. Particularly, it is interesting to see the percentage of graduates in the physical and life sciences going into the private sector – insights that can help guide professional development training for graduate students. Thank-you for sharing this, and congratulations to the whole team! : )

I draw a somewhat different conclusion than those who recommend changes to the PhD to accommodate diverse career outcomes. Doesn’t the data show that PhDs are already doing well in that regard? They have critical thinking and communication skills, and can learn independently. Many will have strengths in quantitative and research competencies. They also appear to be able to market themselves. So perhaps not a good idea to tweak too much something that is already working.

Almost 12% of these U of T graduates are unaccounted for, so I take (minor) issue with the way these data are presented. Why not include the 12% as ‘unknown’? Would that not be a fairer depiction of the data? What does leaving the 12% out get you?

While it is possible that some of the 12% landed tenure-track positions, it is unlikely that many did, otherwise they would have been easier to track down. It would be interesting to know the male:female ratio for the 12%. Is it more or less evenly split, or not?

Most of the extensive data provided on the Dashboard of the University of Toronto School of Graduate Studies web site can be viewed with or without the unknowns:

http://www.sgs.utoronto.ca/about/Pages/10,000-PhDs-Project.aspx

Thanks.

Interesting that U of T is the top employer in the PSE sector for its own PhDs. It would be interesting to know how many of those n=3147 PhDs who are now employed as faculty (tenure+teaching) were hired by U of T. Does U of T like to hire its own?

About 10% of the U of T PhD graduates from 2000-2015 who are currently professors are employed by U of T, and of all of the professors that U of T hired over the period 2000-2015 about 15% have their PhD from U of T.

Thanks for the details. A very interesting dataset and one that should prove helpful for graduates e.g., to assess the possibilities post-PhD. Hopefully it is inspiring for them. I hope other institutions follow your lead and compile such data.

It is so wonderful to see more research finally being done on the fate of those who are actually being trained to be researchers themselves, our doctoral candidates and graduates. According to a recent news story, Statistics Canada is even talking about restoring their survey of doctoral graduates. I’ve always found it amazing how many billions of dollars we spend collectively in Canada on the research enterprise, especially in our nation’s universities, and yet how little we invest in actually evaluating the actual impact of that research activity.

For those considering pursuing a doctorate, the message is to do your own research first before investing some of the best years of your life and career. There is no shortage of data out there, especially now, to show that only approximately half of PhD candidates will ever complete their doctorates, and of those who do complete only about 1 in 3 will become tenured professors. For most, the financial return on investment is minimal at best. And thanks to Reinhart and everyone else who is trying to shed more light on this often obscure part of the labour market.

This is an ambitious project, and a big step forward for university transparency about PhD career outcomes. University of Toronto is a major producer of PhDs and highly regarded in graduate education, including the career development of PhDs. The 10,000 PhDs interactive data interface is a powerful tool for prospective students considering graduate study, current graduate students and postdocs, university graduate program directors, career development professionals, and policy makers.

For readers interested in comparisons to U.S. data, there has been recent action in the U.S. as well. Stanford University, Wayne State University, and (in the life sciences) most recently a set of 10 universities in the Coalition for Next Generation Life Sciences–though none of these is nearly as large a dataset as what U of T has offered here. This is a growing trend, with Council of Graduate Schools also launching a career outcomes initiative in the past year. This type of data analysis and transparency opens the door to a shift in predoctoral education from apprenticeship to holistic training of future PhD professionals who will contribute to society in many ways.

I learned of the 10,000 PhDs initiative when visiting U of T last year, and it is exciting to see it come to fruition. Congrats to Reinhart, Liam, and the undergraduate researchers I met last year who took on this project with a passion. I look forward to seeing what comes next!

Congrats to the whole team for putting together an amazing resource! Not only is the data valuable and interesting, it is presented in a very unique way. I love having the option to toggle features on and off, creating different types of graphs I am most interested in seeing. You can learn so much more by engaging with the data rather than reading a static document. Well done!