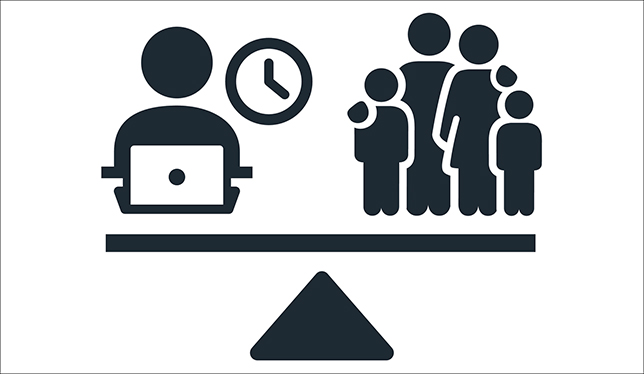

The fine art of balancing family and work

The problem of equity is not new, nor is it unique to science, though I sense we’ve been ready to solve it for a long time.

I wasn’t planning to become the first woman to serve as dean of science at McMaster University. The job was open and the opportunity was certainly inviting, but I hadn’t seen myself in the role. I was busy raising a family and was nicely – though sometimes barely – managing to balance my home life with my research, teaching and academic service at McMaster, where my husband is also a busy science researcher and educator.

The university’s provost, David Wilkinson, who had earlier led an initiative to identify and correct an imbalance between the pay of men and women faculty members, asked me why I wasn’t applying. I explained that I couldn’t really consider a job that would require me to make my family a lower priority, and that would see me working evenings and weekends, when my three kids needed me at home and at the rink.

The provost was concerned by my response. He said the problem was not with my commitments. The problem was with the job. If qualified women were not applying because their other, completely legitimate responsibilities were keeping them from even thinking about applying, then the reality and the perception of the job simply had to change, and he asked me if I had any suggestions on how to fix that.

I decided that the best way to address the problem was from within. So I applied, and here I am, still new in the job, finding that in addition to leading the faculty of science at a major research university, I have also become a kind of symbol, complete with an additional set of expectations.

The reaction to my appointment surprised me. People I didn’t even know wrote and called, glad that a woman was in the dean’s office, and seeing it as a hopeful sign of broader change to come. That’s fine with me. I am happy to serve as an example that it is possible for a woman to be an academic leader in a field historically dominated by men, without my family having to pay the price.

Now I have a duty to respond to those hopes and to be mindful of that in everything that I do, and I’m ready to take it on. If we’re not comfortable having others place more hope in us, then I don’t think we should be leaders.

I know that I’m privileged in many ways: by living in Canada, by my upbringing, by the opportunities I’ve had. My mother and father instilled in me the idea that of course girls and women can do whatever they want. My Grade 11 chemistry teacher took me aside and told me I should think about a career in science. Until he said that, I hadn’t considered it.

My commitment now, as part of creating the best possible climate for science teaching, learning and research at McMaster, is to make equal opportunity less a matter of privilege and more a matter of course – for women and men, and for anyone who faces barriers.

When I was a graduate student, one of my mentors showed me this kind of life was possible by going for a run every day at lunch. He kept his running gear in the lab. He left work every afternoon to pick up his kids from school. He got his work done very successfully. He also looked after his health and his family very well. That made a huge impression on me. He showed by example that it is possible to find balance in this career.

The problem of equity is not new, nor is it unique to science, though I sense we’ve been ready to solve it for a long time. The Government of Canada is smartly moving matters along by changing its process for awarding Canada Research Chairs. It will now withhold CRC funding from universities that do not meet its equity mandate. In Britain, the widely adopted Athena SWAN (Scientific Women’s Academic Network) initiative lays out practical ways to break down gender barriers in the STEM fields.

While on an exchange in England, I saw something that made so much sense that I was surprised no one had thought of it earlier. Every meeting across campus stopped at 4:30 p.m. This was the scheduled end of the standard workday and anyone who had a commitment, family or otherwise, could leave – and that is what they did, with no judgment placed on them. These seem like little things, but they matter.

Here, shortly after I started as dean, we were looking to fill a senior position. Following our traditional protocol would have meant that candidates had to be nominated, not apply directly. My reading had shown me that, for whatever reason, women are much more reluctant to ask someone to nominate them. Now we just let people apply. If we can bring this kind of thinking into every conversation, to see what we can do and what we can improve, I’ll call that a success for everyone.

Maureen MacDonald began her term as dean of science at McMaster University on May 1, 2017.

Featured Jobs

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

2 Comments

http://dailynews.mcmaster.ca/article/some-progress-but-barriers-remain-for-women-faculty-mcmaster-studies/

Former Social Sciences dean Charlotte Yates led the task force that produced the report on the pay imbalance between men and women faculty.

Very nice article and a pleasure to read. I was the first female academic in my research group and I am also starting to raise my own family now. This article has been a good reminder to keep at it and that you’re allowed to redefine roles as you move along in your career. I think the point about role models is also spot on – and that men can be good role models for work-life balance too!