Status hunt drives U.S. recruitment

Prestigious American universities have long exerted a gravitational pull on Canadian academia.

Every decade or so, Canadian academics discover — with fresh horror — that a large number of their colleagues come from American universities. Op-eds emerge, declaring either the death of Canadianization or its survival, sprinkled with anecdotes from a few departments. Meanwhile, those of us who have spent years looking into professors’ CVs have been watching this predictable cycle for decades.

The latest round in University Affairs features Ari Gandsman‘s warning of systematic Americanization squeezing out Canadian talent, while Dominik Stecuła sees Trump’s academic crackdown as Canada’s opportunity to attract displaced American scholars. Both bring compelling anecdotes, but they’re missing key parts of the story.

What is unfolding is more complicated and nuanced: While both authors treat current pro-American hiring patterns as deviations from an imagined Canada-centric norm, such a norm existed only briefly — if at all — at many of Canada’s leading research universities. In the social sciences, especially, faculty hiring reflects a clear transition in influence: from British-trained scholars in the first half of the 20th century to a dominant reliance on U.S.-trained faculty after the Second World War.

The Canadianization movement of the 1970s and early 1980s sought to alter that trend, leading to formal policies in 1981 that required preference for Canadian citizens and landed immigrants in all aspects of academic hiring. But for the only three Canadian institutions ranked among the top 50 in the 2025 QS World University Rankings — McGill, the University of Toronto (U of T) and the University of British Columbia (UBC) — Canadianization turned out to be just a historical anomaly. Since the late 1980s, a great divergence at the institutional level has created two distinct spheres within Canadian English-speaking research universities, moving in different, often competing, directions regarding the doctoral origins of the scholars they hire.

In 2018, this article’s co-author Francois Lachapelle and sociologist Patrick John Burnett published the award-winning study “Replacing the Canadianization Generation: An Examination of Faculty Composition from 1977 through 2017” in the Canadian Review of Sociology. The Relational-Academia dataset tracked 4,935 faculty across five social science disciplines (anthropology, economics, political science, psychology, and sociology) at Canada’s U15 universities over four decades, with comprehensive PhD data.

The analysis of hiring patterns at McGill, U of T, and UBC — let’s call them “the triad”— reveals the stark reality. Between 1977 and 2017, these institutions drew 65 per cent of their social sciences faculty from U.S. universities and just 22 per cent from Canadian institutions. Of that modest Canadian share, 62 per cent represent cases of the triad trading PhDs among themselves or hiring their own graduates. This leaves a mere eight per cent of faculty positions at these three universities going to PhDs from all other Canadian institutions over four decades.

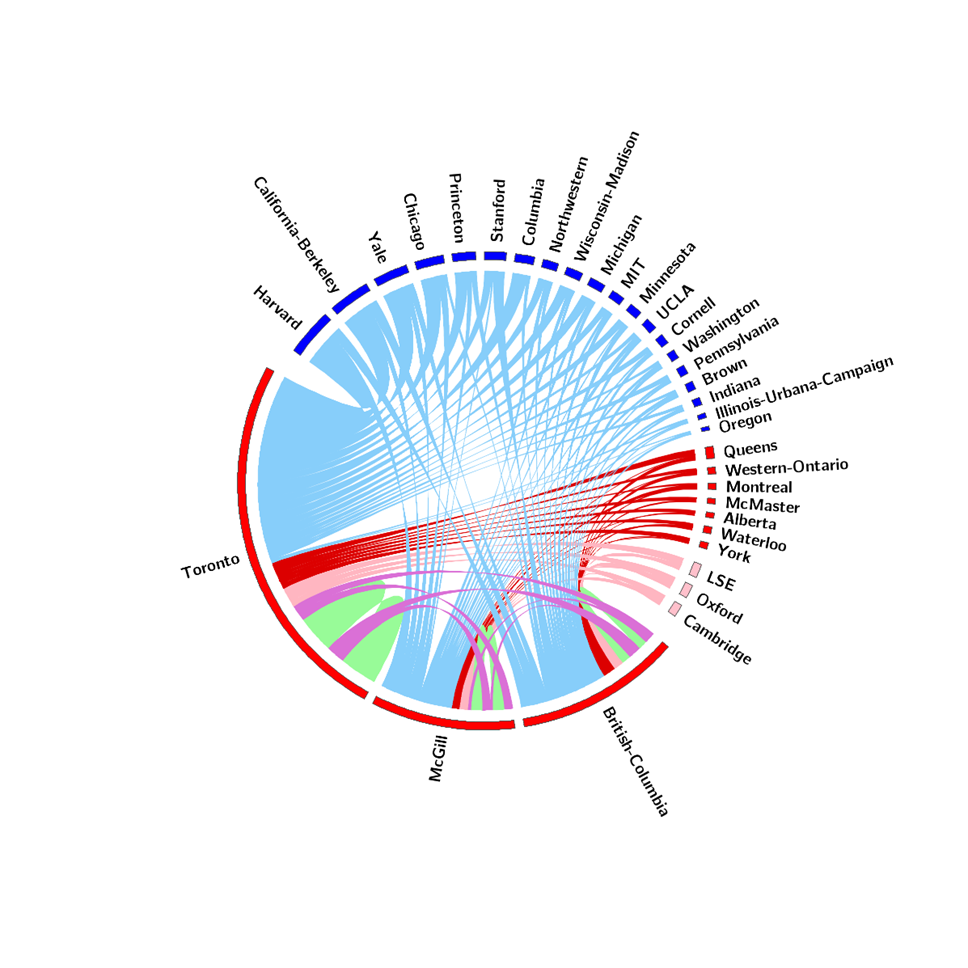

PhD placement patterns at McGill, U of T and UBC, 1977-2017

This diagram maps the aggregate hiring patterns of U of T, McGill, and UBC’s Vancouver campus between 1977 and 2017, showing all institutions that placed at least 20 PhDs across the five social sciences disciplines of anthropology, economics, political science, psychology and sociology.

Blue ribbons dominate the visual space, showing the overwhelming flow from U.S. institutions, mostly elite ones, to these three schools. Harvard leads, followed by Berkeley, Yale and Chicago — the familiar hierarchy of American academic prestige. Purple ribbons represent cross-hiring among the triad, while green ribbons show self-hiring, where institutions recruit their own PhDs (so-called academic inbreeding). Pink ribbons from the London School of Economics, Oxford and Cambridge show some presence from elite U.K. institutions — actually, as much as the rest of Canadian schools combined.

The narrow red ribbons tell the most revealing story: the limited access that other Canadian PhD-granting institutions face in placing their PhDs in the triad network. The green ribbon at U of T alone — representing self-hiring — is as thick as all the red ribbons combined.

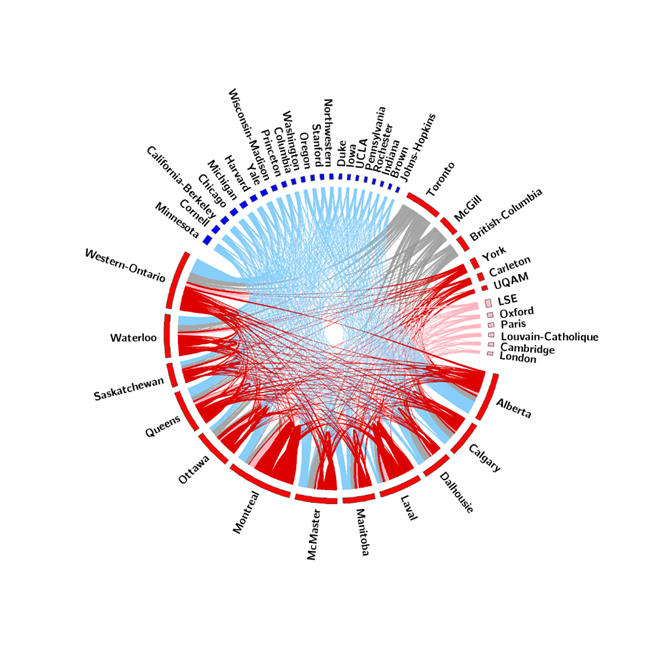

PhD Placement Patterns at Canada’s 12 Other Research Universities, 1977-2017

This figure shows hiring patterns in Canada’s 12 remaining. U15 research universities in the same five social sciences disciplines. Red ribbons now dominate the plot, showing robust circulation among Canadian institutions — the Canadianization movement at work.

The blue ribbons representing U.S. schools are still present but tell a somewhat different story: The highest-prestige brands like Harvard and Yale represent a smaller proportion of the total, sharing space with respected but less renowned institutions. The grey ribbons show the full national weight of the triad, with U of T (with 261 placements), McGill (139) and UBC (110) serving as the top PhD suppliers to the rest of Canada’s research-intensive academic field. It’s a telling asymmetric relationship: McGill, U of T, and UBC primarily look past Canadian academia and outward to the U.S. for their own hiring, securing national and global prestige in the process, while serving as the primary PhD suppliers to the rest of Canada’s research-intensive universities. These three institutions serve as an interface between the global prestige economy and the domestic Canadian academic ecosystem.

We aim to release the Relational-Academia dataset publicly this year. In order to go beyond 2017 and track more contemporary trends, Lachapelle and Burnett’s most recent project, Subfield, has compiled the doctoral origins of all professors employed at Canadian universities across all disciplines for the 2022–23 academic year — the first complete national faculty census of its kind. Such efforts aim to contribute to a critical understanding of how academia and hiring practices are evolving in response to broader institutional and global pressures.

The End of Canadianization?

The continued dominance of U.S.-trained faculty at the triad is not incidental. Even during the height of the Canadianization movement, the triad retained over 65 per cent U.S.-trained hires, while that number declined to below 50 per cent in other Canadian universities. For the triad, status-group dynamics and hierarchies of prestige likely worked in favour of U.S.-trained candidates.

The institutional prestige and visibility of McGill, U of T and UBC likely attracted applicants from elite U.S. programs, whose graduates often carry strong publication records and embedded professional networks. But what counts as a “good scholar” is shaped by more than productivity — status signals, institutional prestige, and cultural fit all matter. For the rest of the U15, the long-term trend toward Canadian-trained hires may have reflected both policy incentives and a commitment to developing domestic academic capacity, as well as a different applicant pool.

But 21st century trends are once again reshaping the landscape. The 2001 policy change that relaxed the Canadian First policy, which had previously required universities to advertise domestically before seeking international applicants, enabled universities to recruit internationally, thus re-inviting the influx of U.S.-trained scholars. This, combined with rising retirements among professors hired during the Canadianization era, an international student gold rush, and intensifying global rankings pressures shifted hiring patterns at schools like McMaster, Waterloo and Western beginning in the early 2000s. Together, these forces have nudged many institutions closer to the gravitational pull of American academia, once again reshaping not only who gets hired but also what Canadian academia aspires to be.

*

Francois Lachapelle, PhD, is the lead scientist at subfield.dev and an academic program market analyst at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

X. Alvin Yang, Dr. rer. pol., is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science and a visiting lecturer at the Free University of Berlin.

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not represent the views of the University of British Columbia, the Max Planck Institute or the Free University of Berlin.

Featured Jobs

- Chief Administrative OfficerUniversity of Toronto

- Sociology - Tenure-Track Position (Crime and Community)Brandon University

- Finance - Faculty PositionUniversity of Alberta

- Engineering - Assistant or Associate Professor (Robotics & AI)University of Alberta

- Medicine - Associate or Full Professor (Kidney Health)Université de Montréal

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

I ended up the other way around. Since the Canadian academic market is small and its prefers international scholars, I ended up working in the USA. I am looking forward to go back home to Canada, but it would be as a retired professor.