In academia, we need two types of researchers: divers and surfers

Once the value of ‘interdisciplinary’ is truly accepted, academia will significantly benefit.

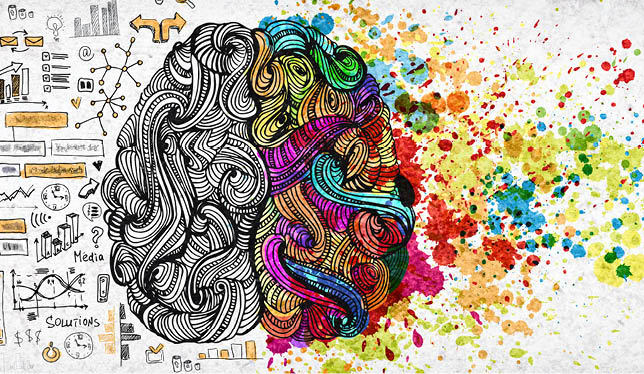

It could be argued that there are two types of researchers in academia: divers and surfers. Divers go narrow and deep with their research. They pick a broad spot in the ocean, jump in, and gradually narrow down to explore what that thread of the ocean has to offer. In the original spot they pick, there is a decent amount of other people, and most can communicate with each other about what they see.

As they dive deeper and more narrowly into the thread that interests them, there are fewer people. Communication between divers gradually becomes more difficult since what the divers see becomes more detailed. When divers are several threads away from each other, they have no idea what the other is saying; they can’t communicate. We could define “experts” as divers.

The surfer is interested in discovering connections between what different parts of the ocean hold. They have binoculars and scuba gear on them. As they travel, they use their binoculars for horizontally scanning which areas are most connected to where they currently are. They go to those areas next to continue connecting the dots. They also use their binoculars for vertically scanning downwards to see what threads of the ocean are most relevant to the connections they’ve made. The problem is binoculars can’t see that far down. This is where the scuba gear comes in handy. When relevant threads are found, the surfer pauses their journey, throws on the scuba gear and does some diving. However, they don’t go as deep as the diver. They go as far as they need to, gaining relevant information, resurfacing, and then continuing to surf.

Why we need more surfers

Academia is geared towards producing experts. Being an expert is viewed as being a diver, so academia wants divers. Cambridge Dictionary defines an expert as “a person with a high level of knowledge or skill relating to a particular subject or activity.” When it comes to academia, a “particular subject” could be seen as too vague a description. Is it the overall discipline, the subdiscipline, or the specific area within the subdiscipline? We can apply this to the overall discipline of philosophy as an example. Does the “particular subject” of philosophy count as philosophy, moral philosophy, or animal ethics?

Academia has misunderstood the meaning of “particular subject” by viewing subjects too narrowly. Even if we assume the broadest category, the overall discipline (i.e., philosophy), to mean the “particular subject”, the way academia has understood this definition has still been too restricted. Another way to view a “particular subject” is horizontally. This means understanding a “particular subject” as spanning across disciplines. For example, we could view a “particular subject” as a discipline that integrates the knowledge of concepts in political science, biology, philosophy and economics. Now, no such field exists. There is no name for it. But that is no reason for it not to be a “particular subject”. After all, the divisions of academic disciplines are artificial; we could have sliced them up differently. We could have sliced them horizontally instead of vertically, so why not think of them as both? Once we’ve done this, we can free up the definition of expert. Experts can be both divers and surfers.

Overspecialization, discipline territoriality, and the limited definition of “expert” often prevent this. The culmination of these factors also leads to a certain snobbery from divers, who dominate academia, to view surfers as superficial researchers. This exacerbates the problem of not hiring and supporting surfers.

Integrating knowledge is equally important to deepening it. Surfing is equally important to diving. Once the value of “interdisciplinary” is truly accepted, not merely as a remark but acknowledged through action, academia will significantly benefit.

Tejas Pandya is a master’s student studying philosophy at Dalhousie University.

Featured Jobs

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

4 Comments

Organizations such as the Human Development and Capability Association do surfing exceptionally well. They have experts from several disciplines who work together on human development. The organization integrates their work among theorists, practitioners and publicly. They have research frameworks that uncle people as real participants in their research design. This type of work is difficult to do within an organization of only experts.

You are correct that surfers are not as valued as divers but should surfers. Surfers also have the capacity to engage more practitioners and can offer better connections to the public. Finally but not exhaustively, surfers can see the storm and know how to weather the changes on the horizon.

Hi Tim, it’s great to hear that organizations such as the Human Development and Capability Association engage in surfing and that they do it well.

It does seem like surfers are, in general, better able to connect with the public. Perhaps this is because the work surfers do is, in general, more interesting to the public. Most work that divers do, since it is so narrow, is probably uninteresting to most people. This is not to say that divers work is unimportant. The work of divers is very important. It’s just probably not interesting to most people. I wrote another piece in University Affairs called “Academia needs public academics” that you might be interested in.

I also like your point that “surfers can see the storm and know how to weather the changes on the horizon.” This is spot on.

Interesting piece. Made me think of Isaiah Berlin’s analogy on thinkers – Hedgehogs and Foxes. Perhaps most surfers are foxes (know many things that are somewhat related), and divers are hedgehogs (know the one thing well)!

During my career and while applying for a professorship in the 80s, one of the external reviewers was for lack of better words will call him stupid narrow-minded or plain racist. He criticized my research as a surfer researcher (your definition) and wanted my research to be as you write a diver. the committee for whatever reason agreed with him it did not help that the chairman and I did not get along and I lost the promotion. the fact of the matter is I won an accolade for my research (internationally) which would be called translational research and very practical to my field. I also happen to figure out who is that reviewer and I am sure it’s easy to figure out who the external reviewer’s letters are because we get redacted copies of the letters. The ironic thing is that the second reviewer was from Harvard University and well-known in his field (but not in a department like mine ) but an expert in my research field ) he said “if the applicant had been in another university and in a department matching his qualification he will have been automatically promoted to the professorship for his research, publication and service and other contents of my CV’S .it did not help that this was the era of racism at the universities for non-white., i am sure it is still going on

So here is my recommendation for any young investigator

1- I agree with you that there are 2 types of researchers divers and surfers

2- Select a department which acknowledges that there are two types of research and promotes people based on this category.

3- get appointments in a department which matches your qualification what I mean by that is if you are a dentist like me and as a double qualified specialist (Periodontist and Maxillofacial surgeon) and a Ph.D. Like me get a job in dentistry not in biochemistry, physiology, or anatomy your promotion will be faster. As one colleague who had similar qualifications to me told me in these departments you are neither fish nor a fowl which is defined as Neither one thing nor another; not belonging to any suitable class or description; not recognizable or characteristic of any one thing.

Sincerely

Dr k.A Galil professor