How do you stop sexual violence on campus?

Alleged assaults at Western prompted policy reviews across Ontario, but it’s unclear what changes will come from them.

The second week of September was warm in London, Ont., with temperatures in the mid-20s and sun shining – a picture perfect start to the fall semester at Western University. A committee of upper-year students had planned out the Orientation Week schedule, full of mixers and rallies, a chance for incoming freshmen to get a sense of the school’s culture and bond with their classmates. Hundreds of excited students, antsy from a year of pandemic-induced remote learning, poured onto campus, ready to begin their university lives.

By the end of “OWeek,” the university had received four complaints of sexual assault, and social media posts alleged that more than 30 students had been drugged or assaulted in the school’s Medway-Sydenham Hall. A police investigation was launched, and while officers obtained no official reports of assault, the damage was done.

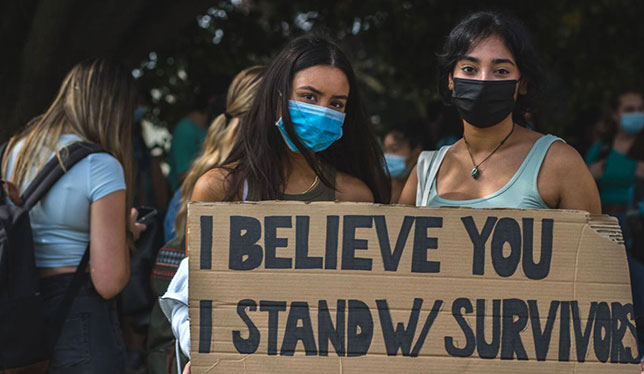

Students organized a walkout in protest, calling for change from university officials. Meanwhile, news of the allegations spread across Canada, leading many to wonder what, if anything would change.

“I, along with a lot of other students, was very disheartened and angry and also heartbroken,” said Eunice Oladejo, who sits on Western’s University Student Council, and is president of the Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance. Ms. Oladejo said in the past, the school hasn’t always responded to incidents effectively. She called this incident a turning point for the university, and hopes that officials take notice. “I want to see the changes, the actual changes that will impact what our students are experiencing on and off campus.”

Substantive changes are the goal, say Western officials. The university’s newly formed action committee met for the first time in early November. The committee, which has several student members, will meet regularly with the aim of identifying gaps in the school’s sexual violence policies. Western is also in the process of hiring and training new safety ambassadors, upper-year students who will work at the school’s residences at night. All students living in residence will also undergo mandatory training on sexual violence and consent.

Seeking a cultural shift

While Western looks to implement these and other changes, officials acknowledge that the broader issue is not policy based, but a much-needed cultural shift. Nadine Wathen is a Canada Research Chair in Mobilizing Knowledge on Gender-Based Violence. She also co-leads the action committee, and said the events at Orientation Week “reinforced the party culture at Western, and certainly aspects of rape culture.” Dr. Wathen also acknowledged that improving the school’s policies can only take them so far. “We have a really strong policy and a 17-page implementation and procedure guide to that policy. But if people don’t feel safe, or don’t feel that things will be taken seriously, then it’s all moot, isn’t it?”

It’s this balancing act of institutional policy and informal culture that has prompted provincial action. Jill Dunlop, Ontario’s minister of Colleges and Universities, announced that all postsecondary institutions in the province have until March 2022 to improve their sexual violence policies. Students who come forward with disclosures of assault or violence cannot be investigated themselves for things like alcohol use, and school investigators are no longer able to ask students irrelevant questions, including looking into their past sexual history. The intention is to reduce stigma and barriers that students face in coming forward.

These mandates were already in place, but Ms. Dunlop said the province was able to “speed up the process” after the news about Western broke. While the mandate states the minimum threshold the schools need to reach by March, how they do it and what their sexual violence policies look like at the end is up to them, said Ms. Dunlop. “We provide the framework for campuses, but then we need to ensure that campuses themselves, and universities and colleges, are doing the best they can to support students in providing a safe environment.”

‘Universities could go even further’

The question, of course, is if these changes are enough. Will they achieve what both provincial officials and universities are trying to achieve? That is, will they tangibly make schools better for students?

Yes and no, said Bre Woligroski, the coordinator of the Sexual Violence Resource Centre at the University of Manitoba. “Universities could go even further, generally,” Ms. Waligroski said, though she is happy to see the Ontario mandates and the impact they will have across the country. At the University of Alberta, for instance, school officials recognize that what happened at Western is not unique, and are reviewing the policy with an eye toward training for likely points of disclosure. The government in British Columbia launched a postsecondary program focused on informed consent, and in Quebec, a large research project is looking at how and when people disclose instances of assaults. Other provinces, like Manitoba, have laws in place similar to the Ontario mandates, that require consistency among postsecondary institutions.

In terms of tangible efforts, Ms. Woligroski describes things like environmental scans of the campus, to see if the layout is safe and well-lit at night. As for policies, Ms. Waligroski points out a crucial flaw in the system. “Policy is actually the thing that happens last… so using policy as a tool of social change isn’t helpful.”

Instead, the biggest change a school has to make is often the most difficult, and hardest to pin down. “In terms of changing the conversation about Western as a party school, it’ll take some time for that to change,” said Terry McQuaid, director of wellness at Western, and the other co-lead of the action committee. “I see the right people at the table, having a conversation, and we’re all invested.”

Ms. Oladejo describes these changes as a good first step, and hopes to see the follow-through from Western, and other Ontario schools. The provincial mandates are based on recommendations from the Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance, and Ms. Oladejo hopes that schools keep looking to their students to lead the way. Until then, she said student groups are “looking to the stakeholders to make a change on their campuses so that we’re not seeing this over and over and over again.”

Featured Jobs

- Canada Impact+ Research ChairInstitut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS)

- Engineering - Assistant Professor, Teaching-Focused (Surface and Underground Mining)Queen's University

- Soil Physics - Assistant ProfessorUniversity of Saskatchewan

- Director of the McGill University Division of Orthopedic Surgery and Director of the Division of Orthopedic Surgery, McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) McGill University

- Anthropology of Infrastructures - Faculty PositionUniversité Laval

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.