Tracing Alberta’s environmental history

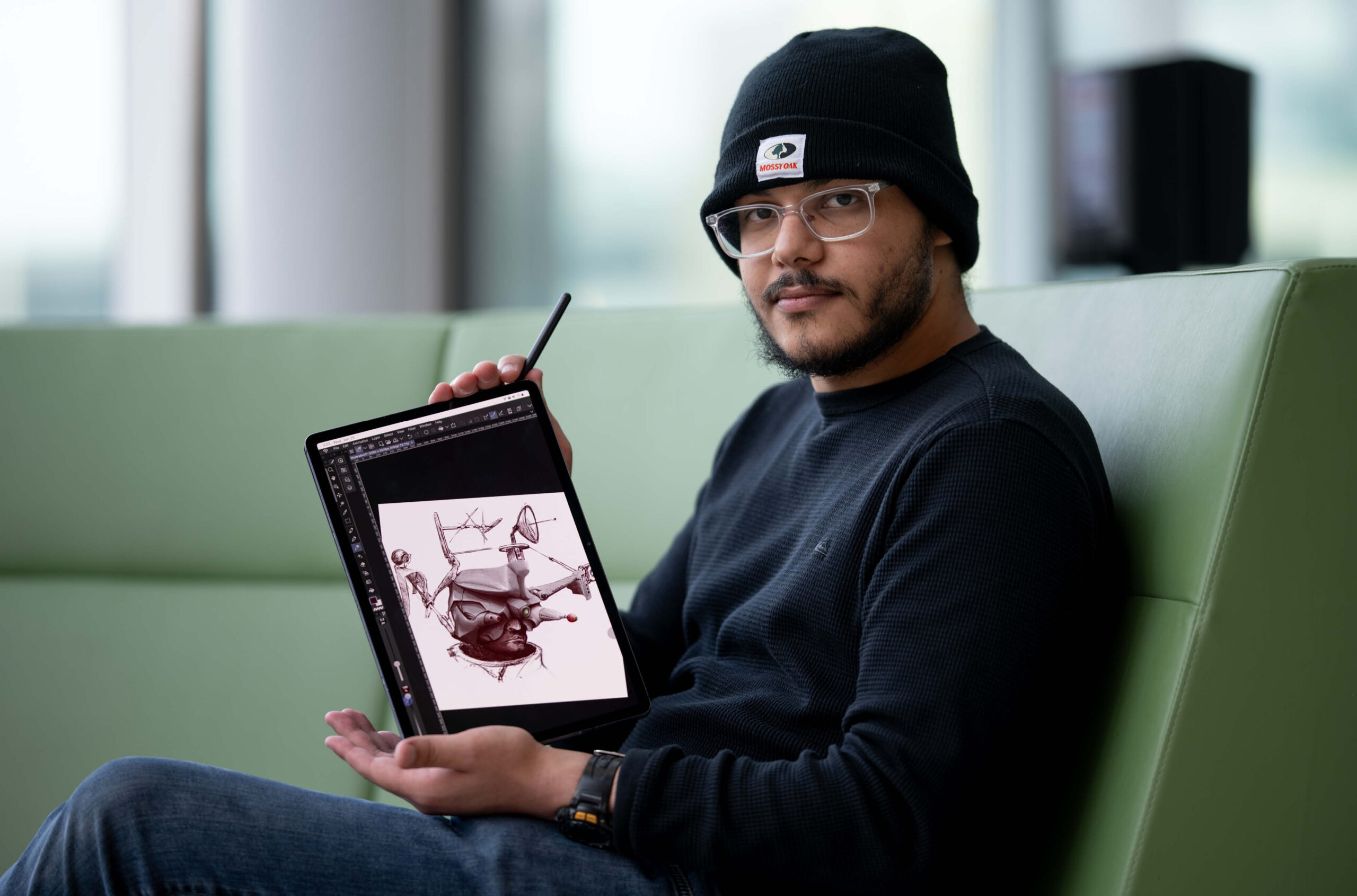

Students go ‘beyond the microscope’ thanks to a partnership between MacEwan University and the Royal Alberta Museum.

In a third-year earth sciences course at MacEwan University, students train their microscopes on small plant and animal subfossils collected from soil, sediment, bone and other samples. By going beyond rote work with prepared slides, students get hands-on experience with sample analysis and the chance to discover clues about how the environment has changed over thousands of years.

Robin Woywitka, who teaches the course, explains that Alberta was completely covered in ice 16,000 to 24,000 years ago. The ice slowly began to recede, scraping the surface, and the land was ice-free by roughly 13,000 years ago, the time period students are examining through the samples.

“This gives us baseline information about how climate and the world worked before we started playing with it,” said Dr. Woywitka, an associate professor of earth sciences and anthropology. “That helps us contextualize the magnitude and potential effects of what we’re doing today through industrial practices and land use practices.”

In the course, the first few labs focus on basic skills, like how to analyze bones, how to perform pollen analysis, and mapping. Students choose which technique they liked the most, and based on that, select the real-life project they want to work on, allowing them to pursue their interests.

The samples come from the Royal Alberta Museum, using collections that have been understudied or are part of an ongoing project at the museum.

The alternative to using real-life samples would be looking at prepared slides in the lab, which is a more rote exercise, Dr. Woywitka said.

“Take slide X, go through it, tell me how many aspen pollen grains you saw and how many fir pollen grains you saw, then use Excel to make a graph,” he said. “It is useful – it teaches you the skill – but it doesn’t give you the why, and I think in science, you really need to have the why.”

He explained the benefit of examining these samples is students get to see one part of what it’s like to be a professional geologist or palaeontologist. “They get to see how geology, paleontology, and archaeology interact with environmental legislation,” Dr. Woywitka said. “They get to see the regulatory process, a little bit of how museum collections work, and [gain] practical skills.”

One project had students working with bones from lakes in eastern Alberta, and by examining them, this helped museum staff understand the diversity of animals in the lake.

“Some of the initial information that the museum staff need to create a full assessment of that material is provided by us here, and eventually some of this stuff could go on to be in exhibits or become part of a master’s program,” said Dr. Woywitka.

In addition to providing students with hands-on experience, this course also allows students to hear from various voices in the field.

“I teach the class, but [museum staff] come in, and they support at particular times in the process, and that exposes students to different voices,” he said. “Each one of these people is an expert in what they’re doing.”

Featured Jobs

- Finance - Faculty PositionUniversity of Alberta

- Engineering - Assistant or Associate Professor (Robotics & AI)University of Alberta

- Sociology - Tenure-Track Position (Crime and Community)Brandon University

- Architecture - Assistant Professor (environmental humanities and design)McGill University

- Chief Administrative OfficerUniversity of Toronto

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.