University-prison partnership brings hope to incarcerated learners

The educational initiative “was humanizing when every aspect of imprisonment is dehumanizing,” says a former participant.

In a makeshift classroom at a correctional facility in Southern Ontario, some 20 students – half of them incarcerated at the facility – sit in a circle alongside a professor. While the professor is responsible for framing discussion topics and structuring class activities, students are encouraged to direct comments at their peers, linking personal perspectives and experiences to the class readings.

The students are participating in the Walls to Bridges (W2B) program, which was launched by the faculty of social work at Wilfrid Laurier University in 2011. It is an offshoot of the U.S. Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, a partnership between American institutions of higher education and correctional systems founded in the late 1990s. W2B has offered 40 university courses to date in Ontario and Manitoba, reaching upwards of 700 “inside” and “outside” students.

“We have a group of instructors and alumni that meet every two weeks, and one of our main functions is to provide a five-day annual training for educators interested in learning our teaching model and how to establish W2B classes at their home institutions,” said Shoshana Pollack, a professor of social work at Laurier and the W2B coordinator.

Over the past year, for-credit courses have spanned the fields of women’s studies, English, philosophy, criminology and social work, to name a few. The participating universities are University of Winnipeg, University of Waterloo, University of Windsor, University of Toronto, York University, Ryerson University and Laurier – the latter serving as the national hub for W2B thanks to the support of the Lyle S. Hallman Foundation. The courses are held at five participating provincial correctional facilities, as well as the federal Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ontario, which serves as the flagship site for W2B.

According to Dr. Pollack, this is possible thanks to a sense of civic responsibility and community engagement on the part of educational institutions. “All classes end with a final ceremony in which students receive a certificate of completion. Inside students don’t have to pay tuition because the universities who are involved are all committed to absorbing the cost of the course, as well as paying for their books.” Universities further support W2B with flexible admissions requirements for inside students, and by allowing professors to teach courses as part of their regular workload despite the small class sizes.

Tiina is a former inside W2B student and one-time Laurentian University undergraduate – she was two courses shy of completing her BA in religious studies when she came in conflict with the law. “I never finished,” she said. “My whole trajectory went off from there with criminalization, poverty. I didn’t have confidence, I didn’t have a voice and I was very depressed, a very dark time.”

Things began to change for Tiina when a close friend of hers was selected for a W2B course being offered at the prison. “She invited me to the closing ceremony,” said Tiina, who noted that the participants were all wearing the same W2B t-shirts. This apparently concerned the guards, as they could not tell the university students from the prisoners. “That got me very excited – there was no difference between students.”

Rachel, another W2B alumna, had completed a master’s degree in community psychology prior to being incarcerated. The program, she said, “was humanizing when every aspect of imprisonment is dehumanizing. Going to class was like a break from prison. I felt valued and intelligent again in a safe space where we could talk about oppression. In other programs, you couldn’t critique the correctional system, but W2B was completely different.”

The introductory class sets the tone by including different ice-breaker activities, said Rachel. “The outside students coming in might have assumptions about criminalized individuals and they need to work through those. Everyone might come in a little bit nervous but by the end of the first class there usually is a lot of cohesion.”

Rachel completed two W2B courses prior to her release. She has since been admitted to the PhD program in criminology at the University of Ottawa, where she is looking forward to starting in the fall.

Canada is lagging behind

W2B is not about providing students from outside the correctional system with the opportunity to mentor or help criminalized individuals, said Dr. Pollack. Nor is it merely about transcending the physical walls of prison. Rather, she said, W2B creates collaborative learning communities within correctional settings so that university and incarcerated students may pursue for-credit courses and learn the class material together through dialogue and experiential methods.

If this seems innovative, even cutting edge, that’s because Correctional Services Canada and their provincial counterparts are well behind other countries in terms of evidence-based rehabilitation practices, said Michael Bryant, former attorney general of Ontario and currently executive director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA).

“Canada is actually lagging behind the United States, which we tend to regard as one of the most backward countries out there when it comes to crime and punishment in the Western world,” said Mr. Bryant. “One of the purposes of sentencing as described in the Criminal Code is rehabilitation, but there simply can be none for someone seeking to restart their life through education if they are not given access to any of the educational tools.”

Personal computers, for example, have been prohibited in correctional facilities in Canada since 2002, with prisoners having only very limited access to off-line machines. Without ready access to computers, much less the internet, it is very difficult for incarcerated individuals to further their education. “Paper-and-pen correspondence courses are very few and far in between because most have gone online,” Dr. Pollack explained. “When there is access, course fees are prohibitive, and even then, the internet is needed for basic research. We do our best to provide resources and let inside students write papers by hand.”

In addition to the obvious physical barriers in prison, “there are also institutional barriers all around,” said Rachel. Facilities have the power to impose a number of arbitrary limits on prison programs, she said, which means that inside students can be kept out of classes for a long list of reasons. “Maybe you are being disciplined for something very minor that is nonetheless deemed unwanted behaviour, or maybe it’s just an escort that is unavailable. There’s no consistency and you become angry, frustrated. These are some of the invisible walls.”

Mr. Bryant, who also serves as the general counsel for the CCLA, shares in the frustration. “This shows how bogus the claims are that corrections in Canada involve any rehabilitation. Anyone visiting a provincial jail or a federal penitentiary sees firsthand how backward and just plain old the system is. We know from Statistics Canada that most people who go into jail come out in about six months. … Do we want them to get an education and rehabilitate when they are inside, or do we want them to come out worse off than they were before?”

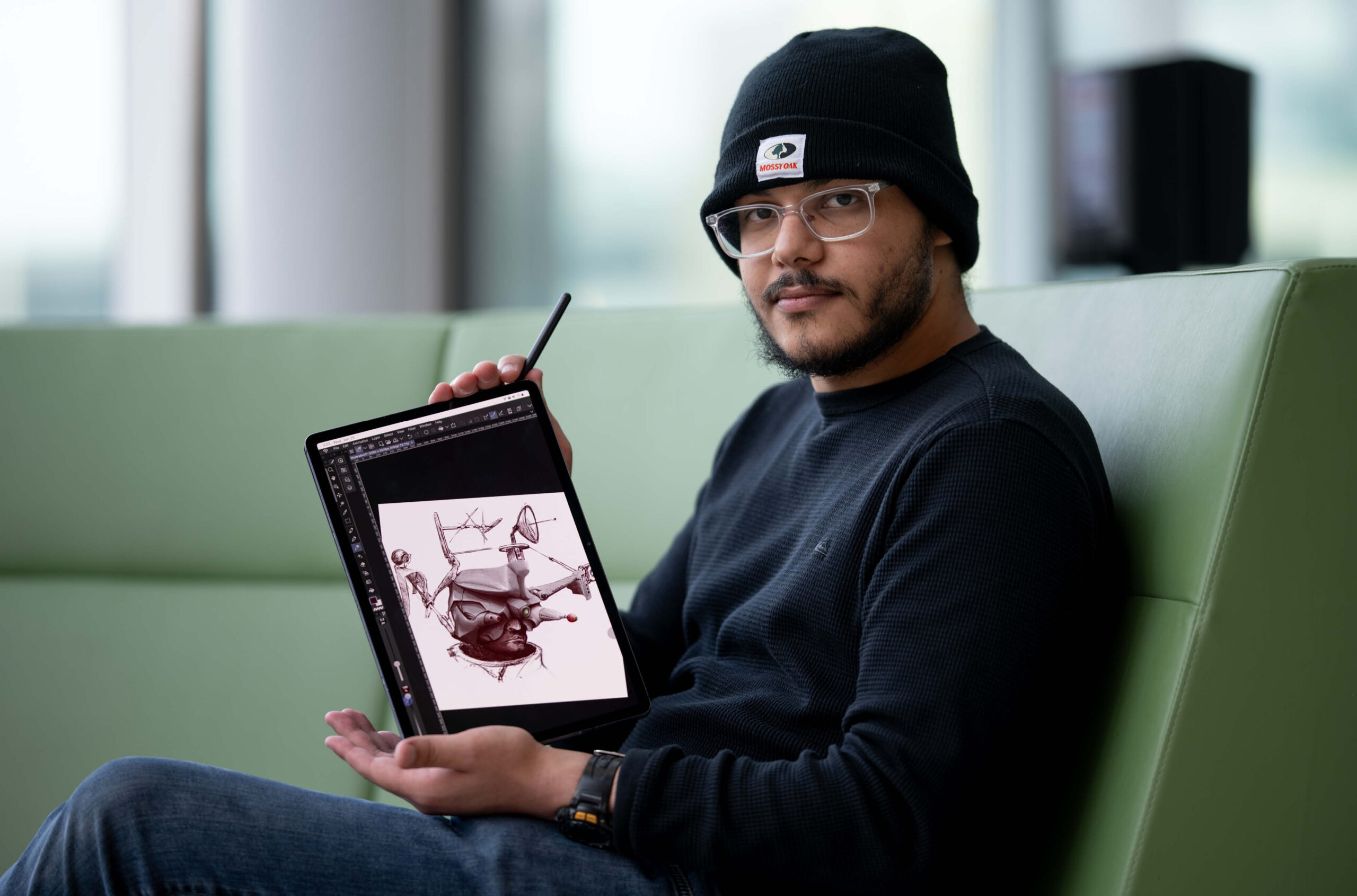

Mercedes Rowinsky-Geurts, an associate professor of Spanish at Laurier and a 3M National Teaching Fellow, set up Inspiring Futures, a W2B bursary fund to support the reintegration of former inside students by assisting them with their studies upon their release. Tiina, who completed two W2B courses of her own since attending her friend’s closing ceremony, went on to pursue an MSW and is the first recipient of the award. Each year, W2B works with the office of the registrar to raise money, but funds are limited.

Nevertheless, there are many success stories of individuals – criminalized and not – whose lives have been transformed by their W2B experience, said those involved. None of this would have been possible if not for the generosity of socially conscious donors and the work of committed educational reformers and volunteers.

“The support is unbelievable,” confirmed Tiina. “One of the reasons I had failed in parole is that my mom had passed away while I was incarcerated. I had nobody, no friends, I had only ever been in abusive relationships. Once I went through W2B I felt a web of support holding me up, it gave me reasons to succeed. … There are people being released now that I’ve never met, but it’s important to me to be as welcoming to bring them into that same supportive network as possible.”

Featured Jobs

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

2 Comments

Great article, good luck!

I was incarcerated in Headingly’s Women’s Correctional Centre 2015-2018. It was an amazing opportunity to participate in the Walls-To-Bridges program in 2017.

To have outside students come into class with us, to be given an opportunity, to be taught and treated by the professors like a normal person, to be awarded credits, and to have to amazing support from absolutely everyone involved in and out, is one of the best things someone locked up could ever experience. It made something count for all that time and gave a positive experience and story to tell, that gave the women motivation and reminded us that we are capable women who made a mistake and a future is possible!