Free speech on campus: are we being too careful not to offend?

It would be a shame if the lesson learned is simply to remove the controversial bits from your course.

The issues of freedom of speech and transgender rights, highlighted by recent events involving a teaching assistant at Wilfrid Laurier University, remind me of my first year as a university instructor in the late 1990s, when I taught a communications course on advertising at York University. (Yes, I understand that the status of a TA is different than that of an instructor, but I think for the purposes of this anecdote, the principles are similar.)

While teaching the course, I saw an ad for Sauza tequila in the campus newspaper. It featured a photo of an attractive, swimsuit-wearing woman, with the phrase, “She’s a He,” written across her chest. The ad’s tag line read: “Life is Harsh, Your Tequila Shouldn’t Be.” (The ad didn’t identify the model, who in fact was Caroline Cossey, a transgender model.)

In that glorious era before PowerPoint, I made a transparency of the ad and presented it to my class by saying: “What do you see here?”

Right off there were chuckles from a few students. One said the ad was funny and edgy. Then other students opened up. Some thought the ad was sexist, that it objectified women like other ads for beer and spirits. They wanted to know what was meant by, “She’s a He.” I told them the model was a transgender woman, who had been born male. They replied that the ad was mean-spirited then, since it was wrong to “dictate” someone else’s gender identity like that.

I presented them with information on forms of social prejudice experienced by trans people. We discussed what types of social responsibility resided with the advertiser, the ad agency and the campus newspaper in all this.

I asked them how such an ad featuring a transgender person might embody a more socially positive message. I got answers like: “She Was a He. Life is Full of Possibilities. So is Sauza.”

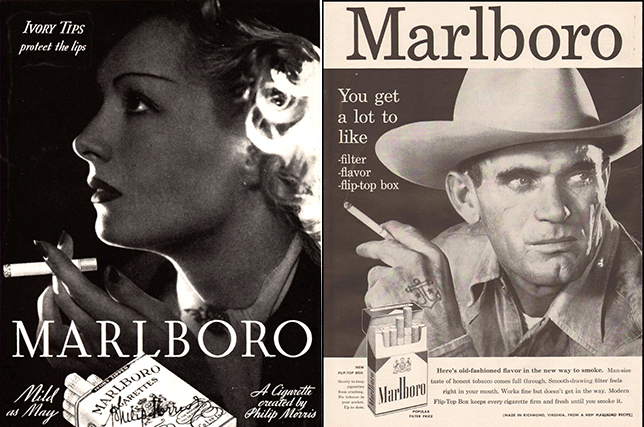

We then discussed a core feature of advertising: its ability to assign meanings to products independent of their function or material makeup. I reminded them of how Marlboro had been marketed to women in the 1940s and how a successful advertising campaign had soon after transformed the brand’s meanings to one of rugged masculinity, personified by the Marlboro cowboy.

If advertising’s putative power turned on its ability to transform the meanings of products, I asked, why then did so much advertising merely reinforce the social status quo or common stereotypes?

At the end of this discussion, I told them that I viewed the ad as transphobic, a term few students then had heard of. This conclusion flowed in part from many of the points raised by the students. In the five or so times I taught that course, more than a few students who had initially chuckled at the ad told me later how the discussion had helped them assess the social impact of ads like this in a new light.

In fact, I came to see how the initial chuckling formed part of the overall learning experience. Such instinctive, “common-sense” responses, shaped by ideology and social setting, were (and are) not unusual. How else to account for the ad’s multi-week run? An ad seen initially as funny or harmless by some in fact contained a lot more meaning and context. The instructor’s job was to unpack this, laying it out for discussion and analysis.

How would this have gone had I prefaced my discussion by saying that I was about to show a transphobic/socially harmful ad? Not as well, I suspect. The students would have been primed to merely align their responses with my prior statement.

Turning back to recent events at Laurier, I ask myself: would I today advise a TA or recent PhD graduate lacking job security to teach such material in a similar manner? Probably not.

To do so today risks getting student complaints that the instructor had created an unsafe, even “toxic,” learning environment by not initially denouncing the ad. Or that the instructor had encouraged students to laugh at the ad or had equated transgender people with the cancer-plague of cigarettes. Who knows? Some department heads might worry how certain constituencies on campus would respond were the matter to go public.

Suppose word of such a complaint went beyond the campus, as happened at Laurier. In today’s polarized climate, the instructor risks being tagged with all sorts of negative descriptors. Faculty members on hiring committees or those evaluating grant applications might prejudge or dismiss outright such a person. So maybe best just to remove the controversial bits from your course.

What’s at stake with the Laurier incident goes far beyond a department’s ham-fisted treatment of a teaching assistant. It strikes at the very core of what universities should do for their students: present topics in ways that foster free discussion and debate and corresponding forms of critical thinking and self-reflection.

This approach is not tidy; unexpected, sometimes objectionable, things get said. The overriding concern, however, should not be to protect students from the perceived harm arising from hearing opposing views.

Daniel J. Robinson is an associate professor of media studies at Western University.

Featured Jobs

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

8 Comments

Sir, what you described above is an example of good teaching about a controversial issue. I was not in the classroom of the Laurier TA at the time the incident happened, but based on the transcript I read, the TA position was that she NEUTRALLY presenting two different positions. That sounds very different from what you described above. I think most reasonable people would agree that neutrally presenting transphobic positions is not very good teaching, and it can be harmful. And the fact that this TA has gone on national TV since and complained about the university CUDDLING students, well that is not neutral at all. I think it is clear where she stands on the issue.

It is really unfortunate that Free Speech has become the rallying cry of trolls who use their platform to target members of a minority group (trans and Muslims are particularly popular targets of these people). They are free to say what they want of course, but people are free to protest these trolls as well. When it comes to a university lecture hall, however, you cannot lose sight of the power dynamics in such contexts. With this power comes great responsibility speak in a reasonable and measured ton , and to be mindful of the individuals in the room, to ensure your students do not feel target for their identity, and to ensure ignorant or hateful ideas are confronted with the light of reason and knowledge.

It is incredibly misleading to talk about the Laurier incident as a free speech issue.

So the teacher is to guide students to conclusions? In a course that is the length of a term or even two, I find it useful to explore ideas in a neutral way as the course opens. When we lift out a particular lecture to examine, its easy to find fault. But growth and understanding take time. To open with a neutral stance, and allow students to share and explore ideas is something I allow to happen in my class. The weeks pass, the discussion grows and, ultimately many answers (or better questions) are discovered along the way. Learning takes time that few seem to have patience for now.

Jordan Peterson is not transphobic.

His position against compelled speech can be presented neutrally without risking harm to anyone.

I don’t know Mr Peterson personally, but I think it’s unfortunate that he’s making his point at the expense of people who already feel marginalized. I assume this is so that he’ll get maximum exposure for his grievances; I wish he would aim for a bit of compassion instead.

I think what you meant to say is that Shepherd complained about Laurier “coddling” their students. If they “cuddled” them, they would have been Weinsteined in social media, and all involved would have been fired or resigned.

Though it’s clear that Laurier doesn’t “inspire lives”, neither do they cuddle their students.

Sir,

I am afraid you are missing the point by comparing your teaching experience with Shepherd’s.

A “phobia” is an unreasonable fear of something. The Sauza ad, contrary to your claim, induces neither fear nor hatred. It plays with people’s expectations and desires. You instructed your class into nevertheless “unpacking” a “hidden” negative meaning from the ad and into rejecting messages like that in favour of “socially positive” ones.

By teaching your students not how to define terms and weighing arguments, but what to think, you did the opposite of Shepherd. Shepherd got harassed to the point of tears for showing a clip from a TV show. Nobody in that clip even criticized trans people; the question discussed was: should the government *force* Canadians to use trans pronouns? Matte, the trans activist in that clip, declared that “it’s not correct that there is such a thing as biological sex.” Peterson, his opponent, explained his position that when government uses its power to force people to use trans speech, in this case trans-pronouns like “zir” and “xe”, it does so illegitimately.

In her tribunal, Shepherd’s supervisor at WLU declared it not “necessarily true” that all viewpoints should be valid at a university and that her neutrality was “kind of the problem”. In other words, she received the treatment she did because unlike you, she failed to instruct her class into “unpacking” a “hidden” meaning from Peterson’s words and to reject his message.

That does not, in my opinion, reflect what students, parents and taxpayers expect from a university – and what academic used to expect from themselves.

Thank you, Daniel Robinson, for this eloquent defence of the classroom as a place to stimulate thinking about controversial issues. With the current concern about “safe” spaces, it is difficult to argue for the value (and necessity, in my view) of addressing challenging, controversial topics with our students. What’s the point of going to university if your classes only confirm what you already know/believe? I want to be challenged by ideas that are not “tidy” and often objectionable, so I very much hope that my students do as well. I think it’s our responsibility to show them how to meet the objectionable and unexpected head on.

Daniel, though I agree with the conclusion of your article, I think you don’t go far enough here. What Laurier did to Lindsay Shepherd was an egregious violation of her free speech rights.

We all know that professors do not generally micro-manage their teaching assistants’ seminars, so Laurier’s mea culpa that they should have managed hers rings hollow. I’ve had at least two TAs who literally disappeared for months at a time, one refusing to mark exams, yet the department in question didn’t discipline them. This is clearly a moral issue, not an administrative one – though I suspect you’d agree with this.

Deborah MacLatchy’s “apology” looked like an IRA gunman was holding a Kalashnikov to her head. WLU is sure to suffer financially when the middle class in the GTA stop sending their sons and daughters to this splendid beacon of rationality (dear Torontonians: my alma mater, UW, is just down the street).

Further, the only reason this has become a cause celebre is because Lindsay had the canny wit to record it. I guess we all have to start carrying around a recording device – I would recommend Samsung tablets, as they have very nice sound quality and there are lots of free audio apps on Google.

Lindsay showed the Peterson video to encourage debate, to engage a dialectical discussion in a CRITICAL THINKING class. Note the word “critical” in the course title. Leaving aside our fundamental Charter rights, I think we are entering a zeitgeist where both profs and students are afraid to even broach certain issues surrounding identity politics – I’ve found this in pretty well every course I’ve taught over the last decade. There is a rightthink and a wrongthink, as Orwell predicted, and pretty well everyone knows what they are. It’s very difficult to get students to even hint at the wrongthink, therefore difficult to get people to discuss both sides of an issue. In this scenario, O’Brien has been replaced by angry anonymous people and groups on social media, who insist that we’re all wrong to thing that 2+2=4.

As you hint, as a TA or contract professor, you utter wrongthink at your peril. That’s why I’m keeping this comment on the meta level, avoiding the substantial issue.

Also, as you say, the usual response by untenured teachers is to let sleeping dragons lie – to simply not bring up controversial issues in classes, thereby ignoring the debates going on in mass media on shows like Bill Maher and John Oliver (not to mention Fox News). To my mind, universities have passed the baton of public debate to comedians, expunging all but the most mean-spirited humour from discourse. That’s why Seinfeld doesn’t play US colleges. Who would you rather have running a university – Bill Maher, or the students of Middlebury College? At least Maher is funny.

As for people who think that a defense of our liberal constitutional rights is only for racists and trolls, there are lots of places in the world where such rights are trampled on or laughed at. Such places are not usually shining exemplars of human development, but either dictatorships or failed states caught in the grip of civil war. To extend Nathan Rambukkana’s metaphor in his infamous attempt to re-educate Shepherd, it all started with the Sudetenland – the idea that hurt feelings and “compassion” trump (or should I say Trump) factual truth and vigorous debate. Though I would never say my conservative political opponents are “literally” Hitler. For one thing, most don’t have moustaches.

Watching video clips of the radical students of the late 60s and early 70s is like watching a science-fiction film. In 2017, Mario Savio would be shamed on social media out of schools like Laurier before the autumn leaves fell.

Safe spaces are empty spaces – empty of critical thought, logic, reason and empirical facts. Though perhaps that’s what senior administrators want – the intellectual equivalent to fast food outlets (my inner Sherlock just lit up…).

Without freedom of thought and expression, universities are hollow institutions. Orwell was right.